The budget

A few observations

Overall, the government is cautious and conservative, with an eye on inflation

There’s nothing to get too excited about in the budget. The government has been cautious and conservative: that’s about right for our economic situation. Its emphasis is on suppressing inflationary pressures. That’s in line with governments’ responsibility to keep the economy on an even keel, known as “stabilization” in the public policy textbooks. That has been difficult in view of the inflation it inherited from the previous government. That inflation, together with the associated rise in interest rates, cut into living standards for many Australians.

The government has dealt with this fall in living standards (called a “cost of living crisis”) through increases in cash benefits – tax cuts and electricity rebates – and improvements in the social wage, particularly in the care economy. Because of the government’s concern about inflation cash benefits have been modest. The cash and social wage benefits, between them, have achieved a small re-distribution of income towards those most in need. It’s an unspectacular redistribution but it would not have been achieved had the Coalition been in office.

There are three much bigger challenges for the government if it is re-elected. One is to put the economy on a sustained path of prosperity after decades of neglect by successive governments, mainly Coalition governments, who failed to undertake structural reform of the economy. Another is to attend to worsening disparities in wealth and opportunity. And the third is the need to raise more revenue.

In presenting a budget just before an election, the government has missed the opportunity to put forward a strong reform agenda, particularly much-needed tax reform. Such is the strength and savagery of the populist right in Australia, and the timidity of Labor governments, that proposals for economic reform are always met with an all-out scare campaign, which would be overwhelming in a pre-election period. That means the task of improving our revenue base, not just to improve the cosmetics of the budget but more importantly to fund important government services and to redistribute income, has been kicked down the road.

As usual, we are overwhelmed with comment, most with a partisan bias, and most around particular themes – the fiscal deficit (expected), and those small tax cuts (a surprise).

You can go to the government’s budget website which leads to all budget-related documents, but as usual the most informative document, for most purposes, is Budget Paper 1, Budget Strategy and Outlook. It adheres to a standard structure, and while the narrative is the government’s, it is largely free of the blatant political spin found in the budget speech. For those seeking a short read John Hawkins and Stephen Bartos of the University of Canberra also have a Budget at a Glance in the Conversation.

What follows is mainly from Budget Paper 1.

The economic story – lower inflation, stronger labour market

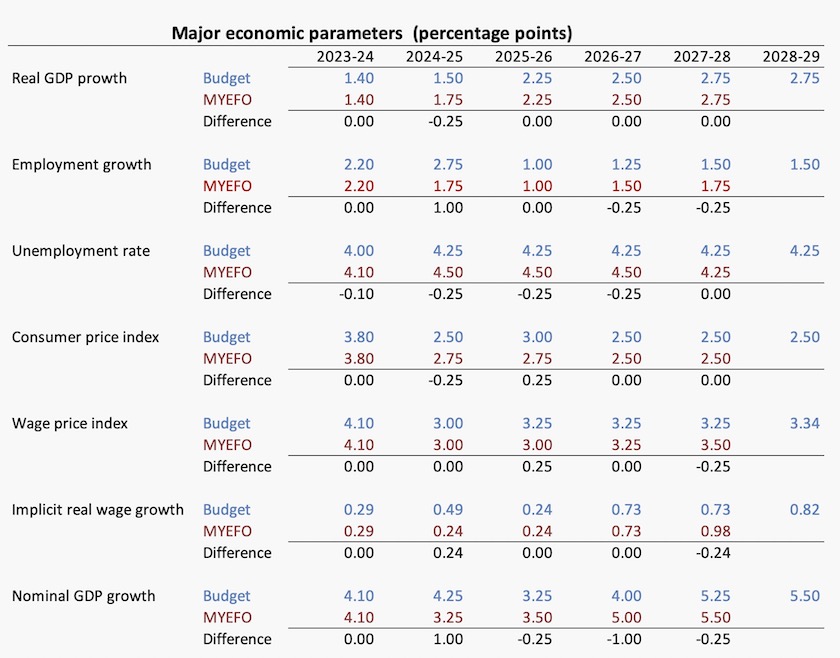

The economic story in Budget Paper 1 is captured in the statement of major economic parameters, summarized in the table below. This compares the budget with the Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, presented in December. This comparison shows that there have been some small changes in economic outlook in the last few months.

Inflationary expectations dominate these forecasts. It appears from this table that the Treasury, and perhaps even the Reserve Bank, have finally settled on the idea that we can have 4.25 percent unemployment without going into an inflationary spiral, and it is notable that the government, and financial commentators, are drawing attention to the 2.5 percent inflation rate, which falls right in the middle of the Reserve Bank’s comfort zone. The temporary rise in inflation to 3.0 percent seems to be an allowance for worldwide inflation boosted by Trump’s trade wars.

This budget could be seen as a negotiation with the Reserve Bank: the government has delivered a conservative budget and it’s up to the Reserve Bank to offer another interest rate cut next week, on April 1. The everlasting bargain between fiscal and monetary policy.

The fiscal story – a cautiously conservative budget

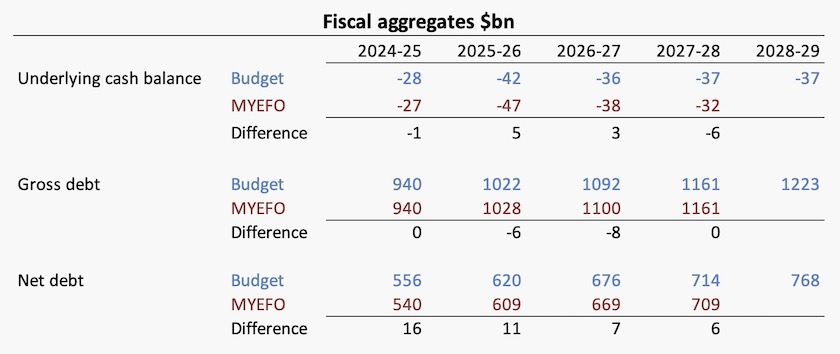

The second table in Budget Paper 1 is the fiscal outlook, reproduced below with a comparison with the figures in the Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Most of the media noise (which passes as debate) is around the fiscal balance, and true to form, the Coalition claims that they’re the superior economic managers because they run surpluses. The Coalition’s line is amplified, usually unintentionally, by journalists who put a normative spin on fiscal outcomes, calling a surplus “good”, a deficit “bad”, and using silly terms like “budget repair”.

That’s all misleading. There is no virtue in a surplus; there is no failure in a deficit.

The government’s task is to use its fiscal power to stabilize the economy, and a modest deficit at a time of global uncertainty is a wise decision. There is the question whether a government should have a plan to bring the budget back into balance, but in our present political climate no one should expect a government, presenting a budget a month before an election, to include a plan to collect more revenue.

The fiscal deficits forecast in in this budget are between 1.1 and 1.5 percent of GDP. Most of the world’s finance ministers would call that a “balanced” budget. The average deficit in the Euro area is 3.4 percent of GDP; in the US it’s 6.6 percent of GDP; in the UK it’s 4.5 percent of GDP. Similarly our government debt is very low by the standards of other “developed” countries.

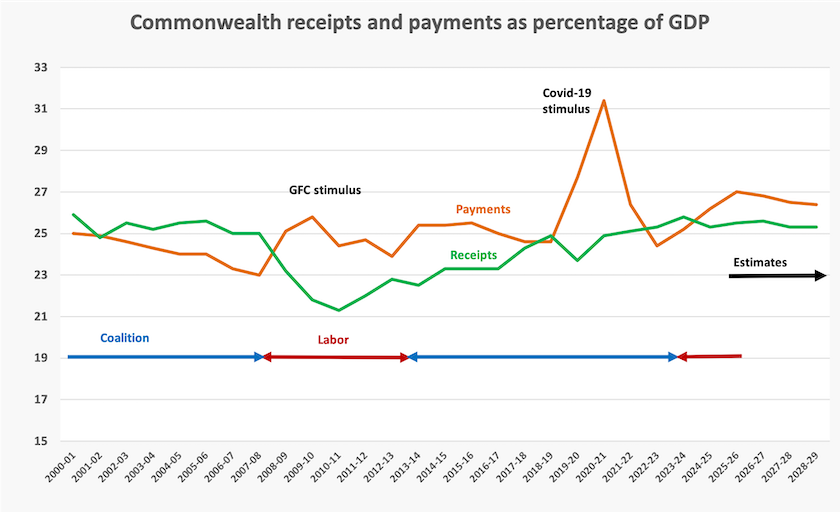

Australia’s fiscal outcomes over this century so far are summarized in the graph below. The only time there has been a sustained run of surpluses was during the commodity boom in the early years of this century. That was hardly good management: the Howard government dispensed the benefits in the form of tax cuts, while it let the standard of public services deteriorate, energized housing price inflation, and neglected investments in education and infrastructure which would have made the economy more resilient. Our economy is still bearing the costs of the Howard government’s poor economic management.

The deficit of all time was on the Coalition’s watch – the Covid stimulus. No reasonable person has criticized the government for making such a strong stimulus, but the government was slow to withdraw it (for example by not making “Jobkeeper” a loan rather than a grant). The present government has had to deal with the consequences of that fiscal carelessness. The treasurer’s story in this budget is that the government has done that hard task, while recognizing that it takes time for people to see the benefits in terms of relieved financial stress.

Those tax cuts – unnecessary but understandable

John Hawkins has a separate Conversation contribution on the tax cuts: Tax cuts are coming, but not soon, in a cautious budget. It will be 15 months before they trickle into people’s pay packets, and then they’re modest. In the meantime bracket creep will continue. Income tax receipts are forecast to rise by 4 percent next year and by 6 percent in the two following years. Governments rely on bracket creep when they know any proposal to reform taxes raises a scare campaign from the right.

These tax cuts are estimated to cost $17 billion over 10 years – less than $200 a household. It’s easy to scoff at them, but they align with this government’s practice of making small redistributive moves which, when added up, are substantial.

The politics of these tax cuts don’t need explaining. But even though they’re small, described as a “top-up” by the government, they are significant in terms of our tax structure.

The initial marginal tax rate, applying to people with incomes between $18 200 and $45 000, is to be reduced from 16 percent to 14 percent. That’s a modest, but permanent change to make our income tax scales a little more progressive. It’s enduring, unlike a half-baked idea to reduce fuel excise for a year, and unlike changes to brackets, it doesn’t have to be reviewed as inflation takes effect. It also reduces slightly the government’s dependence on income tax as a source of revenue, strengthening the case for tax reform.

Non-compete clauses – good for the economy, bad for feudal masters

Commenting on the Treasurer’s announcements, economist Chris Richardson suggested that “the eventual benefit to Australians of reforming non-compete clauses will be similar in size to the tax cuts”.

Around 3 million Australians are subject to these restrictions, which hinder them from moving to higher-paid or more satisfying jobs in other enterprises, and which discourage people from leaving wage employment to establish their own businesses.

Removing those shackles can only help improve productivity, but there is resistance from those running small businesses, who haven’t come to grips with the transformation from feudalism to capitalism.

The Council of Small Business Organisations, in making its usual grizzles about Labor governments, has defended non-compete clauses. William van Caenegem of Bond University, writes in The Conversation that banning non-compete clauses is a good move, confirming that it could lift the wages of workers who take advantage of their removal by up to 4 percent, but he notes that the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry calls their removal “heavy handed”.

It is strange that so-called employers’ lobby groups, who often call for removal of regulations that limit workplace flexibility, object to this deregulatory move.

The $150 electricity rebate – poor policy, but the best in the circumstances

I checked my most recent electricity account. Because over the summer quarter my use of electricity and generation from my small solar system were close to balanced, and because I am on a legacy plan, I received $95.77 into my electricity account, rather than the $20.77 as was in my contract with the supplier. That extra was the $75.00 rebate.

Unearned and undeserved.

Those rebates have been poor public policy. A means-tested subsidy to help people invest in panels and batteries would be far more justifiable on grounds of equity, reducing emissions and reducing electricity bills for everyone.

At least this time their extension is only for half a year, the winter and spring quarters, when most Australians’ use of electricity is highest.

The politics are around Labor’s 2022 pre-election promise to reduce electricity bills by $275. The Coalition’s deceit around this promise are covered in last week’s roundup.

The economics are about the influence of electricity prices on the CPI, because these rebates will help keep the headline CPI down. The Reserve Bank suggests that it is concerned only with “underlying” inflation – a measure that looks through subsidies and one-off events. But it is also concerned with headline inflation, because people’s everyday language is about headline inflation – the figure that appears in the press. That headline figure drives inflationary explanations and bids for CPI adjustments in contracts and wage negotiations. The rebates are a clever but regressive way to distribute a non-inflationary cash benefit.

Iron ore – the government’s safety valve

It has become established practice for the government to include a low iron ore price in its revenue forecasts. On Page 184 of Budget Paper 1 is a table reminding us why the iron ore price is so important.

Each $US10 increase in the price of iron ore boosts the GDP by $5 billion, and company tax receipts by $0.4 billion. A similar price decrease has the same effect in the opposite direction. On Page 43 the government states that it has assumed the price will be $US60. At present prices are hovering around $US100. There are similar conservative price forecasts for other mining commodities. Always a useful buffer.

Angus Taylor explains why every economist from Adam Smith to Paul Samuelson was wrong

For some novel economic theory, you can spend 19 minutes listening to David Speers interviewing Angus Taylor about his reaction to the budget. Political commentators have commented on his failure to answer questions about the cost of nuclear power. Other listeners are struck by his unsubstantiated claims about the government’s performance, and his wild claims that electricity bills have blown out by $1300. He’s good at fiction.

Economists must surely be puzzled by three economic rules he put forward in that interview.

One was the idea that public spending should grow no faster than the growth rate of the economy. You won’t find that in any textbook, but Taylor claims it to be a “rule”.

Imagine if that were indeed a rule of economics. Over time the general pattern in all “developed” countries has been for public spending to grow faster than private spending, because as we become more prosperous we choose to spend more on collective goods and redistribution, and because many public services are intrinsically labour-intensive. Imagine if we had applied that rule at a time before there was an age pension, while hospitals relied on charity, and when children finished school at age 12.

In fact over time the optimum public-private share of the economy tends to shift towards the public sector. Contrary to what some on the right claim, the public sector is a productive part of the economy, and an economy with too small a public sector is operating below its best.

Another related “rule” is Taylor’s idea that Commonwealth spending should be capped at 23.9 percent of GDP. This number, with its decimal point precision, has been floating around Canberra for many years, like one of those dead animal smells in your house that you can’t quite trace. It appears that almost all high-income countries, apart from the USA and Ireland, are breaking that rule. Angus had better warn them.

And then there is his idea about our electricity system, asserted with effusive confidence, that the private sector should own the transmission lines, while the public sector owns the power stations.

It’s an Alice-in-Wonderland reversal of economic theory. The generation of electricity is, and should be, contestable, open to private operators subject to the normal conditions of competitive markets. If a technology is too expensive in comparison with others, the private sector won’t invest in it. That’s why no company wants to invest in nuclear power in Australia. By contrast, transmission lines are generally natural monopolies, for which there is a strong case for public ownership, to prevent monopolists from abusing their market power, and to take advantage of the public sector’s lower cost of capital.

Taylor’s biographical entry in Wikipedia states that at Oxford he studied "Smith, Bentham, Burke, Mill, Marshall, Schumpeter, Galbraith, Keynes and Friedman". When his political days are over he will surely be sought after by universities to explain what he found in these scholars’ work to justify his unorthodox departures from mainstream economics.

Dutton’s reply to the budget: good news if you own a Ford Raptor, bad news if you’re an economist

Dutton’s reply to the budget was largely a re-presentation of rehearsed bites about “Labor’s cost of living crisis”, ”the worst collapse in living standards in history”, and statements starting “Under Labor …” followed by every imaginable misfortune that Australians have suffered over the last three years., whatever their cause.

There was a scatter of policy suggestions, mostly uncosted, and lacking any coherent theme. Some were outside the Commonwealth’s Constitutional reach. There were grand promises to improve health care, but they lacked substance.

One consistent, but not coherent, theme was on energy. Although the government’s energy policy has Australia on a path to lower cost and more reliable energy, which will comply with our climate change commitments and which will give us a global competitive advantage in energy-intensive industries, the Coalition is out to wreck it.

Not because they have a better scheme – their gas reservation scheme and their ideas for nuclear power would put us on a path of high-cost energy, requiring heavy government intervention, for decades to come. Their fuel excise proposal sends a clear message about what they think of transport emissions.

This isn’t about policy. It’s about destroying something the government has been building, because it’s the work of wrong government, an illegitimate Labor government, sitting on the treasury benches where the Coalition should sit.

Energy policy is dealt with separately in this roundup, as is his Muskian idea to get rid of 40 000 public servants.

His idea on cutting fuel excise is worthy of separate mention beyond its implication for emissions, because it epitomises Dutton’s crass, populist approach to public policy, directed to the Liberal Party’s base, and because it illustrates the way the Coalition makes up numbers too give a veneer of economic justification to its ideas.

Dutton claimed aimed that cutting excise by 50 percent – 25.4 cents – would save an owner of one car $700 a year, or a family with two cars $1500 a year. Because those figures seem to be high, it’s worth checking them out.

The ABS Survey of Motor Vehicle Use reveals that passenger cars on average travel 11 100 km a year. Fuel consumption figures from the Climate Council reveal that cars presently on the market have a fuel consumption of 6.9 litres per 100 km, while light commercial vehicles (popular among tradies), have a fuel consumption of 9.9 litres. The excise cut would be 25.4 cents a litre.

The sums of saving therefore are:

Cars: 111 X 6.9 X 0.254 = $195 a year;

LCVs: 111 X 9.9 X 0.254 = $279 a year;

Toyota Corolla hybrid: 111 X 3.9 X 0.254 = $110 a year;

Electric vehicles = $0 a year.

Even if we double these figures we come nowhere near the figure of $700 per car.

Such a blatant misrepresentation of easily-checked figures sends a warning about all the Coalition’s figures that are harder to check – on electricity costs, migration numbers, and estimates of the costs of taxpayer-subsidised business lunches. They make stuff up and hope no one notices.

They don’t acknowledge that Australia already has almost the cheapest gasoline among all “developed” countries: among OECD countries only the USA has lower prices. In most OECD countries the retail price of gasoline is between $A2.50 and $3.00 a litre.

Pity about the wrecked suspension

They don’t acknowledge that this form of cost-of-living relief is regressive. Higher incomes are associated with higher gasoline consumption. The government’s tax relief, by contrast, is progressive, and it’s ongoing.

They don’t acknowledge that a large proportion of excise – about 70 percent – goes into road construction and maintenance. Do Australians really want to save a couple of hundred dollars next year, while they see their roads deteriorate further?

And they don’t acknowledge the impact of this proposed immediate fiscal boost. The government’s tax cuts are deliberately delayed to ensure that they don’t come into effect until inflation is definitely squashed. Dutton’s talk in his budget reply speech falsely blames Labor for the inflation it inherited from the Coalition, makes pious promises about the Coalition’s toughness on inflation, and accuses the government of spending too much, while shamelessly introducing a fiscal boost when the economy least needs it.

About the only promise we can believe is Dutton’s assurance that he will be a “strong leader”, not that he will be part of a governing team. He promises that in government his style would continue to be authoritarian – the tough cop whose mind is made up, regardless of evidence or argument. Trump lite.