Other economics

The Albanese government has been too slow in building the public service

“Labor employed 36 000 more public servants”.

It’s true. When Labor came to office there were 171 938 Commonwealth public servants. Three years later there were 209 913. That’s 37 975 more and the budget reveals that this year the public service has grown by another 3 400.[1]

David Speers quotes Dutton on Insiders stating that the Coalition “are not going to have the public service sitting at over 200 000", implying a cut of at least 13 000. But Dutton has consistently said he’s not going to cut any “frontline” services

When he learned that the public service had grown by another 3 400, Dutton became bolder promising that he would cut the size of the public service by 40 000. In his speech in reply to the budget he said “We will reverse Labor’s increase of 41 000 Canberra-based public servants – saving $7 billion a year”. He didn’t mention how much the Coalition would spend on consultants and labour-hire contracts to replace those 41 000.

Note that he would sack 41 000 Canberra public servants. In all, there are 213 349 public servants, 38 percent of whom work in Canberra: that’s 81 000. He wants to sack half of all Canberra-based public servants! Has he thought this one through? Probbaly not.

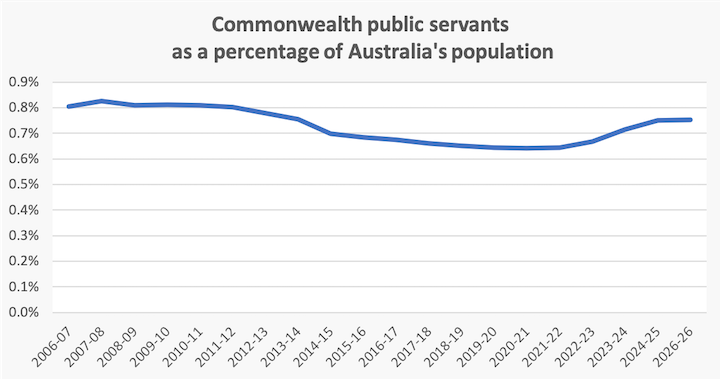

This talk about public service numbers is another example of the Coalition using figures out of context – by using a short time-frame in this case. The public service has grown in the last three years, but that growth is essentially a restoration of jobs the Coalition cut in its nine years in government. The graph below shows the number of Commonwealth public servants as a percentage of the population: it is now back to a little lower than it was twenty years ago when John Howard was in office.

This graph is a replication, with an update from the budget, of a graph in Gareth Hutchens’ post on the ABC site: Why cut thousands of public service jobs? Who came up with the idea?. That post has a great deal more information about public service staffing. In fact the idea of savings to be made through cutting back public service numbers has been a Coalition mantra for the last 75 years, as Hutchens points out.

Public servants are an easy target for the Coalition. Even though only 38 percent of Commonwealth public servants work in Canberra, a little Canberra-bashing is politically costless. The Coalition holds none of the ACT’s five seats (two Senators, three Members of the House of Representatives), and has no chance of winning any.

On the same Insiders program as Dutton first mentioned his plans to cut the public service, Productivity Commission Chair Danielle Wood said that cutting the public service wouldn’t save much, particularly if there are to be no cuts in services: Productivity Commission chair warns cutting public service won't save much money. In fact the Commonwealth runs a lean operation: Steven Hamilton of George Washington University reminds us that public service pay comprises less than 4 percent of the Commonwealth’s spending.

This is a debate we shouldn’t be having, because while we should be concerned about the government’s administrative efficiency, we shouldn’t be concerned about the number of people it employs. It’s because of an enduring image of “fat cats” that governments have been reporting on the number of public servants. In the 1980s the Commonwealth’s Central agencies (Treasury and the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet) abandoned most micromanagement controls on line departments, but they retained staff ceilings.

If we want to see the consequences of public sector cuts driven by thoughtless ideology, Elon Musk, as head of DOGE, is giving us a real-time demonstration. Dutton has promised to establish a DOGE down under, emphasizing public service staff cuts as the priority, and we have evidence from the Abbott and Morrison governments to make a fair guess of the consequences of four possible methods.

(1) Replacing public servants with consultants and workers employed through labour hire companies. The administrative costs alone are high, and when policy and research staff are replaced with private consultants, the human capital of experience and public sector specialization is lost.

(2) Slowing down the administration of services. This is how governments can cut without ostensibly retaining “frontline” services. Passports still get issued, but it takes months longer. The time to get approval for lifesaving pharmaceuticals lengthens. Nursing homes and childcare centres get supervised, but with much longer times between audits. Visas for essential workers still get issued, but probably by the time the applicants have found work in other countries. Projects eventually get environmental approval, but that can be too late.

(3) Cutting complete services, as Musk has done with the US Department of Education. So far Dutton has promised to abolish Welcome to Country ceremonies in Commonwealth agencies, which would save taxpayers about 1.5 cents a year. (See the February 1 roundup).

(4)Using technology to replace public servants. We have seen the stunning success of that with Robodebt.

1. The figure of 36 000 was based on 2024-25 budget papers. There have been minor revisions in this budget. ↩

CPI inflation down again

Almost unnoticed among all the budget din, on Wednesday the ABS published its Monthly Consumer Price Indicator for February, which showed that inflation between January and February was precisely zero.

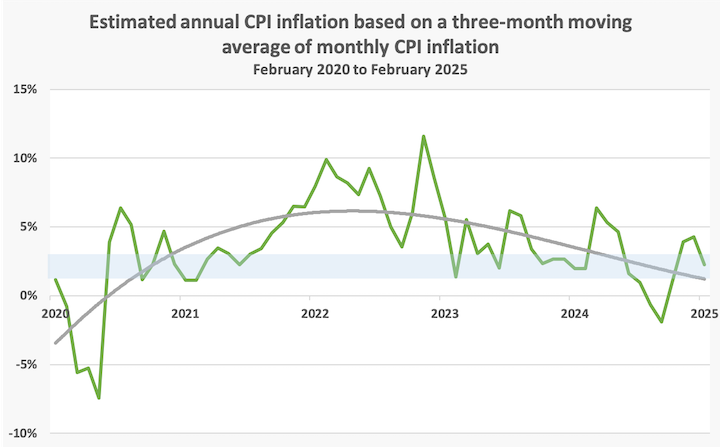

This indicator is volatile, and is subject to more sampling error than the ABS quarterly surveys. But a three-month moving average, shown in the graph below (an update of similar graphs shown in these roundups) gets rid of much of the noise. It indicates that over the three months to February prices rose by 0.56 percent, a rate which, if sustained over a year, would result in an annual rate of CPI inflation of 2.3 percent, well within the RBA’s comfort zone. The longer-term trend, shown in the grey line (a third-order polynomial) suggests that CPI inflation is at the bottom of the Bank’s comfort zone.

The estimates published on the ABS website are for movement in this index over the last twelve months, from February 2024 to February 2025, rather than the three months from December 2024 to February 2025, shown in this graph. The ABS figures show a headline rate over the year of 2.4 percent, and 2.7 percent if volatile items are excluded. As inflation comes down, the three-month and annual measures converge.

Supermarkets – the ACCC tinkers at the edges of a failed market

The ACCC report on supermarkets is weak on recommending reform, but its inquiry has revealed a large amount of research explaining why Australian consumers put up with such a poorly-performing industry.

The Commission’s proposals for reforms are captured in 20 recommendations for minor tweaks to make the market work better, without suggesting any basic structural change to that market. Many of those recommendations are about ensuring that consumers and suppliers are better informed about prices and related conditions such as loyalty schemes.

That’s pretty well in line with the basic textbook approach to market competition. Provided all parties are well-informed, and there are no barriers to entry, the market will look after itself, delivering the best outcomes for all.

Gay Mortimer of the Queensland University of Technology summarises the Commission’s work, and provides some background to the inquiry, in a Conversation contribution: ACCC finds Australia’s supermarkets are among the world’s most profitable – but doesn’t accuse them of price gouging.

The Commission’s report is a case study in the way a duopoly works: university lecturers will welcome it as a teaching resource. There is competition – intense competition – but it doesn’t take the form of simple price comparisons.

There are loyalty schemes to stop customers wandering off to other suppliers. There is confusopoly: even the most discerning consumer can find his or her brain is overloaded with signals about discounts, pack sizes, the value of multiple purchases, loyalty points – anything other than simple price comparisons that one may find, say, in a fruit and vegetable market where stalls are side-by-side.

There is widespread use of price discrimination. Look at those graphs on Page 181 of the report about the price for Twix Xtra Chocolate Bars: hold the price high for a few days, and you can sell them to the customers who don’t care about price, then drop the price, and you will pick up the more price-sensitive buyers, enticed by the advertised price reduction.

Isn’t it funny that those high and low prices for Twix Xtra Chocolate Bars are exactly the same in Coles and Woolworths?

If it found evidence that these price similarities resulted from collusion, the ACCC would be recommending prosecutions. But there doesn’t have to be collusion, because these identical prices arise from the competitive dynamics of duopolies. Nothing for the ACCC to be concerned about.

That says something about the way the ACCC and our governments consider whether markets are working well or not. It doesn’t matter that the outcome for consumers is the same as it would have been if there had been price collusion, because as long as those outcomes occur as a result of market operations, and not a breach of the law, all is OK.

In view of the Commission’s adherence to textbook economics, it’s surprising that their recommendation on barriers to entry is weak. On Pages 12-13 it acknowledges that planning and zoning laws operate to the advantage of Coles and Woolworths, and on Page 163 it shows that Coles and Woolworths are holding on to undeveloped sites, but its related reform is an insipid recommendation that “Governments should adopt measures to address planning and zoning issues”. “Don’t go there” seems to be the advice to government, presumably because the ACCC knows that the government does not want to engage in a fight with state and local governments.

Aber hier nicht wilkommen

It is notable that the ACCC does not mention the 2020 attempt by the German low-price supermarket giant Kaufland to open 20 stores in Australia. At the time there were serious allegations that established interests were colluding to block its entry and it suddenly abandoned its advanced plans. That followed a 2016 attempt by Lidl to break into the Australian market. Surely these deserve a mention.

Nor did the ACCC mention divestiture. There are problems with divestiture: when the Greens and the Coalition unite on a policy it’s a pretty good sign that the economics are crook, but it’s worth a mention.

Divestiture isn’t a great idea, because if parts of Coles and Woolworths were sold as going concerns, the fundamental high-cost business model would not change, and each region, as is the case now, would still face one supplier with the benefits of a locational monopoly. By contrast a new entrant is more likely to offer a better business model.

It seems to be a report prepared for a government that doesn’t want to do much, and that knows the opposition won’t want to do much either. That’s Ross Gittins’ main point in his post: It’s official: supermarkets are overcharging. So change the subject. What it reveals is not just about supermarkets: they’re just one manifestation of our whole oligopolistic economic structure:

But it’s not just the political duopoly that doesn’t want to know about the pricing power of the grocery market’s big two. Most of the nation’s economics profession don’t want to think about it either. Why not? Because it’s empirical evidence that laughs at their conventional model – whether mental or mathematical – of how the economy works.

Even more basically, why do consumers put up with it?

Why are consumers supporting the duopoly?

The ACCC report describes a duopoly with a high-cost business model. It provides evidence of the high cost of that model with its information on profits (why should firms in such a low-risk industry be so profitable?) and in its comparisons with Aldi.

Aldi has an entirely different and lower-cost business model, with far less effort on promotions, no loyalty schemes, mainly private brands, and a small product range that still covers most imaginable needs.

One policy approach, which seems to be the government’s default, is to observe that if consumers are willing to direct two-thirds of their spending to two high-cost firms, when there are lower-cost alternatives available, that’s their business. “You can take a horse to water …”

This view is implicitly challenged by a submission to the inquiry by the Behavioural Insights Team consultancy. It applies the research of behavioural economics to the Australian supermarket industry. Its findings, all backed with evidence, are:

- The supermarket environment may make effective decision-making more difficult for consumers.

- Supermarket practices may reduce the likelihood of consumers making informed decisions about the best value options.

- Supermarket practices may elicit changes to consumer perceptions and behaviours over time.

- Supermarket practices may contribute to consumers deviating from their own interests and prior intentions.

- Supermarket practices may reduce the likelihood of consumers moving between retailers.

However one considers these findings, they are evidence of market failure. That is, in spite of competition, and opportunities for consumers to inform themselves, the market is not working to bring low prices to consumers. The absence of evidence of “price gouging” does not mean consumers are getting a good deal, because there are behaviours – costly behaviours – which result in people paying more than they could under more ideal market conditions.

A more active approach than leaving it to consumers to get hooked into a high-cost market, would be for the government to intervene in the market to ensure it gives a low-cost outcome in line with the economists’ model of competition. The starting point of such an approach is for governments to accept that markets just don’t happen. Rather they are established within existing rules. Zoning, for example, is one such rule.

The government, in saying it agrees with the recommendations (at least in principle), accepts that it can do more to make the market behave a little better in the interests of stakeholders. But if it really wanted to see this market deliver for consumers it could do far more to shape the rules of this market so that it comes closer to the competitive ideal. In line with the economics of market failure governments could:

- subsidize the establishment costs of new entrants;

- prohibit loyalty schemes;

- prohibit land banking;

- prohibit price discrimination in supermarkets unless they can be demonstrated to confer consumer benefits;

- require supermarkets to disclose their promotion and advertising expenditure, which would not be counted as a business expense for tax purposes.

Radical? Only if you think competitive markets are radical.

Don’t worry: the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme is safe

Last week’s roundup had many links to Trump’s trade and other economic policies, emphasizing their effect on Australia. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme was the subject of particular concern, in light of the pressure big Pharma is exerting on the Trump government.

Martyn Goddard, in his Policy Post, goes into more detail about the PBS and provides a reassurance: The PBS is under fire from US drug giants. There’s not much they can do.

Big Pharma spends a motza ($US152 million) on lobbying, and Australia is singled out as doing it harm, but its powers are limited by the nature of the world trade in pharmaceuticals. Goddard rules out the US using restriction of supply as a weapon: we have our ways around that. (Note that the main protection on pharmaceuticals is through industrial property laws, rather than technical complexity or secrets, as is the case with silicon chips. Technically we could replace US-made pharmaceuticals with our own if necessary.)

Goddard dispels any notion that this hostility has come on suddenly with Trump’s election. Democrat governments have not been too friendly to us on trade rules, he explains.

He goes into detail of the operations of our PBS, and how it compares with other countries. We’re not the only country to have negotiated a good deal: this means Australia and other countries should not let the Americans pick them off one-by-one.

Privatisation

In last week’s roundup there were links to and about Adele Ferguson’s Four Corners revelations of serious problems in child care services, and the question about whether publicly-funded human services should be privatized.

Gareth Hutchens takes up the same broader issue in his post: Privatising child care and aged care promised lower costs, more choice. Experts say some consequences are “devastating”. He reminds us of an experience we should have learned from – the collapse of ABC Learning. By the time the company went into administration in 2008, its main achievement had been to project its founder, Eddy Groves, into the top rank of the BRW rich list under-40 age category.

While Hutchens is cautious about all privatization of human services, the question raised by Ferguson’s expose is whether the problem is privatization, or the use of private entities whose raison d’être is to make a profit. (Conversely some not-for-profit organizations can lose touch with their original purpose and become large growth-oriented businesses.) But the common issue is about the objectives and motivations of those providing services.

A reader has drawn attention to a privatization that should definitely not have occurred – the decision by the Western Australian Electoral Commission to outsource staffing of the administration of the election to a labour hire company. In some booths people had to be turned away because there weren’t enough ballot papers.

It is hard to think of any more important pillar of democracy than people’s trust in the integrity of the electoral system. That trust is not just about the absence of tampering, but it’s also about the diligence with which elections are conducted. Are the ballot boxes secure? Is the room free of partisan signage? Are the scrutineers keeping their hands off the ballots?

The mammoth task of collecting votes in Australia is usually done by local citizens who show up to the electoral commissions, election after election, to do this work. For some it’s a small income supplement, but for most it’s a civic duty, performed with pride. Turnover of workers is low, which means there are always experienced staff to help newcomers. They know when there will be surges of people coming to vote, they are experienced in helping people with disabilities, they know the boundaries of their electorates, they are familiar with the difficult names on the roll and so on. These are all small bits of local knowledge that cannot be learned by generic staff recruited by a labour hire company.

Another reader has mentioned the contracting out of the Adult Migrant English Program. Like childcare this is a human-service program heavily supported by public spending. Its administration was subject to criticism in an Australian National Audit Office report last year. Notably, it found:

there are deficiencies in the processes by which the department has engaged advisers and contracted the existing service providers to identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes.

But isn’t innovation supposed to be one of the benefits of privatization?

The ANAO also found that the administering department, the Department of Home Affairs, was devoting too few resources to monitoring providers, and had cut back on the frequency of on-site visits. (Echoes of Ferguson’s findings on child care.)

The reader also referred to wider matters of contract management, covered in the recently-released report by the Parliamentary Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit: Report 511: Inquiry into the contract management frameworks operated by Commonwealth entities.

It is likely that the government’s response on all these matters will be to devote more resources to contract management and supervision – a commitment that will last until some ideologues in the future decide to cut departmental running costs and impose staff ceilings.

The bigger issue should be about contracting out and privatization. Could the resources devoted to contract management be more effectively devoted to supervising public servants delivering the services in-house? Is it possible to capture the quality of human services in metrics such as KPIs set for private providers, or is it better to develop the professional competencies of in-house staff. Can those who work for a for-profit corporation ever achieve the same level of performance as those who work in an organization specifically dedicated to serving the public purpose?

Privatization has been driven by untested assumptions that innovation and efficient service delivery is to be found only in the private sector. That assumption has been found wanting.

Economic and social trends over the first quarter of this century

Two Conversation contributions cover general social and economic trends in Australia.

One is by Intifar Chowdhury of Flinders University: Every generation thinks they had it the toughest, but for Gen Z, they’re probably right. Gen Z (now aged between 13 and 29) is the best-educated generation ever, but it isn’t enjoying the payoffs from education that earlier generations enjoyed. (The reformers who pressed for better access to education didn’t warn that the laws of supply and demand would catch up.) Home ownership is increasingly out of their reach, unless they are part of the inheritocracy, and they are more prone to mental health disorders than people of the same age were in previous times.

Politically they are likely to lean to the left, and, unlike the pattern observed among earlier generations, their left orientation will not diminish with age.

Labor Party strategists may see that finding as encouraging, but if so they’re deluded. There are many more political options than two tired-old parties, and Labor has long abandoned its social-democratic principles.

The other contribution is by John Quiggin of the University of Queensland, as part of his How Australia has changed since the year 2000 series. This one is about the way we work, which is now radically different. He goes through the ABS labour force data over the past 25 years, noting that we are now in a sustained period of nearly full employment, an idea that would have been unimaginable in any period since the 1960s. The nature of work has changed, in a way that has seen a large growth in female participation. And, nudged along by Covid-19, working from home has become established for about a third of workers.