Public policy

Electricity

On Wednesday the Australian Energy Market Operator, recognizing that the spot market mechanism at the core of the National Energy Market had failed, suspended the wholesale electricity market, essentially taking control of the market. That is the market in which “generators” – more familiarly known as power stations – supply electricity through the transmission and distribution network to homes and businesses. They bid in spot markets and in a rather complex process those bids set the market price for short periods.

Blackouts were threatened. Not because there is inadequate capacity to supply the market, but because players in the market were holding back supply – 5 Terawatts or about 20 percent of the demand on Wednesday evening.

In simple terms the wholesale price of electricity at times of high demand – typically early evening – has become ridiculously high, because we have underinvested in renewable energy and for those periods of high demand we are dependent on gas generators and on old and unreliable coal-fired generators. There is enough gas in the country but it is committed to export, and world gas and coal prices are high, because of increased energy demand as the world emerges from the Covid-19 recession and partly because of the Ukraine War. Some generating companies have been taking advantage of those high prices and have held back supply, hoping to cream off monopoly profits.

That’s the simplified story. Josh Gordon, writing in The Sydney Morning Herald, explains the situation in more detail: Where did all the power go? What caused the east coast energy crisis?. Giles Parkinson, writing in Renew Economy, explains the strategic complexities in the way firms play the market to their advantage: The day the fossil fuel industry lost all perspective, and threw away its social licence. And on Wednesday’s PM Tim Buckley of Climate Energy Finance explains why the AEMO had to take control of the market: “War profiteering”: gas exporters accused in energy crisis. (5 minutes)

Unfortunately the media’s language has become somewhat emotive – “crisis”, “perfect storm”, “skyrocketing prices” and so on. It was reassuring to hear the Prime Minister on radio on Thursday telling the public that the government won’t be rushed into reflexive action: the situation is complex and the last thing the economy needs is an ever-changing energy policy.

Had we invested in enough renewable energy over the last twenty years or so, including transmission and storage infrastructure, and in improved building insulation, we would not be in this situation. Even if we had not made adequate investments but had reserved gas for domestic use, we would not be in this situation. But, as Buckley and others point out, when the Coalition was in office it was bitterly opposed to renewable energy and because it was beholden to the fossil fuel lobby it had no intention of depriving multinational gas companies of their profits by requiring them to hold back supply.

While the newly-elected Albanese government tries to handle the situation, the multinational gas companies are making huge profits – around $72 billion a year according to Buckley – on which they are paying no tax and hardly any royalties. The ABC’s Ian Verrender explains where the money is going: How your spiking energy bills are making foreign investors rich, drawing on research by the Australia Institute. Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin explains that our system of collecting royalties on gas is designed in such a way as to result in its being ineffective.

Angus Taylor has left the new government with a wicked economic problem. Under the NEM rules the government and its regulators have no real power to control generators’ prices. They can set a wholesale price cap: it has been set at $300 per MWh which equates to 30 cents per KWh, but that is only to smooth out the market: the generators must be compensated if that price is less than their cost of generating electricity, and there are always bitter disputes about calculating production costs in regulated industries. In old power stations, where the plant is being run down, the cost of keeping them running (the marginal cost in economic terms) is probably very low, but the generators will use every accounting trick in the book to overstate their costs as a basis for “compensation” or “subsidy”, the choice of word being different for the recipient and the payer.

One option for the government is to let the market charge high peak prices and pass them on to consumers as higher prices, but even the cap of 30 cents per KWh, by the time it reaches our meters, in our high-cost network with markups all along the line, would probably be at least 60 cents per KWh. (We are presently paying in the order of 25 cents per KWh for electricity.) And that’s based on the cap that the generators argue does not cover their costs. In back-of-the-envelope terms, if the regulators allowed the costs that the generators claim they are incurring to pass through to consumers, electricity prices would double.

Or the government could subsidise the generating companies for the difference between the cap and their costs, as the NEM rules allow. That subsidy would pass through to gas companies that are already making $72 billion a year and returning next to nothing to the community. That would not go down well politically. A variant on this approach is for the government to pay generators to keep reserve capacity, which many see as a backdoor way to keep coal-fired generators running.

The UK government, in a not dissimilar situation, has responded with a super profits tax on oil and gas suppliers. Callum Foote of Michael West Media is urging our government to do the same: Labor’s first mistake? No windfall tax on oil and gas. This could provide the funds to keep prices under control or to compensate households for high costs. Buckley supports the idea, and warns that Labor could face political consequences if it does not implement such a tax.

That’s a reasonable argument, but it does not take into account our particularly toxic political environment. If we had an opposition party concerned for the national interest, it would be hectoring the government to take action, either through a super profits tax or through fixing the royalties system. But the last time a Labor government tried to implement a resource rent tax or a super profits tax on resource companies the Coalition opposition joined with the resources industries in a hysterical scare campaign.

If the history of the last fifty years is any guide, the Coalition will stop at nothing to render a Labor government powerless, even if that means incurring a huge cost to the national interest. We can imagine what would happen if the government were to follow the UK example and impose a super profits tax: there would be accusations of a “socialist government posing sovereign risk”. Johnson’s Conservative government can do it because UK Labour is not going to oppose it, but it’s quite different for our government.

But perhaps the public mood now is different and the Coalition is weaker than it was in Rudd’s time.

(This article is about the short-term issues in electricity supply, precipitated by a spike in world prices. In the Public ideas section there is an article about the basic design problems in the NEM – a market designed by ideologues rather than by people who understand energy.)

The Reserve Bank stakes its ground

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe appeared on ABC television last week in a long (16-minute) interview with Leigh Sales. He justified the Bank’s decisions during the pandemic, including its decision to reduce rates to 0.1 percent and its promise to hold rates until 2024. (His explanation for having made that promise is not entirely convincing, and he is a little less than clear when he explains why the bank took so long to break that promise.)

Notable is his statement “We will do what is necessary to get inflation back to two to three percent”. Perhaps he is heading off any suggestion that the bank’s mandate on inflation should be more nuanced. He accepts that, even though inflation may hit 7 percent by the end of the year, it would be unwise to move too quickly, but the “two-to-three percent” target remans, without any mention of the cost of achieving that goal if it results in high unemployment. He does no more than hint that the remedies for demand-pull, cost-push, and imported-goods price rises may be different: his focus is on inflation whatever its source. He also dismisses any suggestion that monetary and fiscal policy should be coordinated. In all it’s a strong declaration of independence.

Health policy

Coronavirus

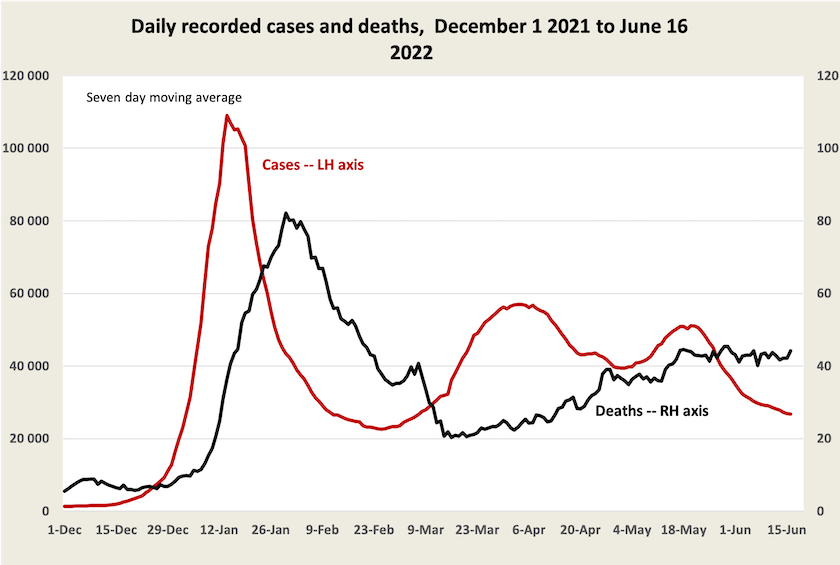

It is still with us. Although recorded case numbers are falling, 40 people a day are still dying of or with Covid-19.[1]

Perhaps the number of deaths – an indicator not only of distress but also of the load on hospitals – will start to decline because recorded cases have been declining for a few weeks. There is generally around a three-week lag between infection and death. But perhaps there has been no significant reduction in cases, just a reduction in recorded cases. Perhaps the protection offered by vaccines is waning. Or perhaps the more infectious strains of Omicron are finding it easier to get through to the unvaccinated.

It is notable that a disproportionate number of recorded cases and deaths are in Victoria. Over the last fortnight Victoria recorded 2.6 daily deaths per million population, while the rates in other states were between 0.8 (Tasmania) and 1.9 (Western Australia). All these rates are high in comparison with those in other “developed” countries, where rates are generally between 0.7 and 1.0 daily deaths per million. Notably New Zealand has a high death rate: is it possible that what we are witnessing is a low summer rate in the northern hemisphere and a high winter rate in our hemisphere? It is also notable that some “developed” countries that succeeded in suppressing the virus early on are now experiencing high death rates. Deaths are high in Portugal and Taiwan for example.

Or is there something peculiar about Victoria? Is there an association between hook turns and Covid-19, or between a football obsession and Covid-19?

If we discovered that Victoria had a rate of automobile deaths twice that of New South Wales, and that the whole country’s automobile death rate was higher than in other “developed” countries, government transport departments would be on to it, with grants to universities, joint projects with insurers, academics and public servants. Is it that public health is still the poor cousin of health care?

Influenza and other infections

Authorities are warning people of the need to get the influenza vaccination. Some states have made it free. The Commonwealth Department of Health Influenza Surveillance Report shows that after quiet years in 2020 and 2021, when public health measures against Covid-19 were suppressing influenza, it is back with a vengeance. Early indicators are that it could be as bad as it was in 2017, one of our worst influenza years in recent times, and it has had an early onset. In 2017, 1200 Australians died with or from influenza. That’s still much lower than the 14 000 who will die with or from Covid-19 this year if our current death rate is sustained.

Also there seems to be an unusually high number of people turning up at hospital with serious manifestations of other viral infections.

1. For comprehensive data on recorded cases, deaths, hospitalizations and more, see the website maintained by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues: Covid-19 in Australia. Data on vaccination is on the ABC’s vaccine tracker, maintained by Inga Ting and her colleagues. The Guardian’s data tracker has further select data, including reported infection rates in regions within states. ↩

The wage case

John Buchanan of the University of Sydney has written in The Conversation summarizing and analysing the Fair Work Commission’s determination on minimum wages. He writes that this 5.2% decision on the minimum wage could shift the trajectory for all workers.

In lifting the minimum wage a little above CPI inflation the Commission is generally in line with other minimum wage decisions over the last ten years, and this increase will flow indirectly to workers on enterprise agreements, over-award payments and individual contracts. Most importantly “it has implicitly challenged the strictures placed on wage increases by both federal and state governments over the past decade”.

Wellbeing

How have we fared through the pandemic?

A group of researchers at Deakin University have pulled together a number of wellbeing indicators, published in The Conversation as 5 charts on Australian well-being, and the surprising effects of the pandemic.

The surprising effect of the pandemic is that there wasn’t really any discernible effect. In fact we seem to have felt a little better off in 2020 and 2021 than we were in the two years just before the pandemic.

The other four charts confirm many of the generally-accepted beliefs about wellbeing. Living with one’s partner is better than living alone, and living with parents leaves much to be desired. Unemployment is lousy, but the idle years of retirement are OK. Retirees find themselves to be no worse off than students, people doing “home duties”, and people who are employed. There’s no sense of “I really miss my job” among retirees, and no sense of an enjoyable life for those who get by on the unemployment benefit, but the temporary “Jobseeker” boost seems to have been appreciated.

On the relationship between income and wellbeing the findings of behavioural economists are confirmed. There’s not much joy from an increase in income, but a lot of grief from a reduction in income – that is, unless our income is low, in which case a rise does count. It looks like the Fair Work Commission, in deciding to provide a proportionately higher increase to low-paid workers, got it right on Wednesday.

The report card from the productivity guardian

The Productivity Commission has updated its performance reporting dashboard – one of its ongoing reportingseries. It reveals a patchy set of outcomes that are at least partly influenced by government policy. For example we’re falling behind on reducing homelessness and reducing rental stress. Enrolment in post-school education is falling. Life expectancy is improving, but the life-expectancy gap between indigenous and other Australians is not closing. There are many indicators into which one can drill down for detail, with disaggregation by state in many cases.

The pandemic does not provide an excuse for falling short in many areas: most of these indicators are long-term.