Public ideas – Australians on Trump’s return

Michael Liffman

Michael Liffman in his Beyond the Faultlines contribution – Was Mencken right – describes what distresses, frightens and dismays him:

It is that so many people do not perceive, or are not troubled by, or even, in some grotesque way, find comfort in, someone as contemptible, dishonest, narcissistic, inflammatory, demagogic, manipulative, cruel, misogynistic, vindictive (need I go on?) as the man they have elected President for the second time.

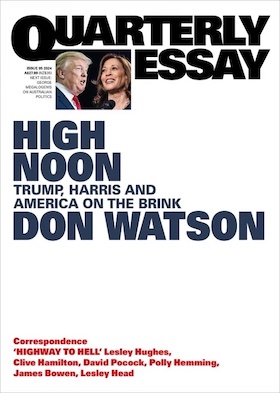

Don Watson

Don Watson’s Quarterly Essay – High Noon: Trump, Harris and America on the Brink – was published only weeks ago, while Kamala Harris was riding high in the opinion polls.

When you read its first 80 pages you encounter a chillingly insightful account of Donald Trump’s successful appeal to Americans. Trump has captured the mood of the Americans who feel left behind: he is “the embodiment of their neuroses” to quote Watson. It’s clear from Watson’s essay that Trump is on a path to victory.

When you read the last 10 pages, however, you read of the tremendous vitality of the Harris campaign. Watson does not make a prediction, but if you had read it before November 5 you would have concluded that a Harris win was close to inevitable.

Watson’s essay is an eloquent account of the way liberal Australians – and no doubt liberal Americans – were thinking. A dispassionate rational analysis pointed to a Trump success, but we could not imagine that Americans could make such a terrible collective decision as to elect someone so crudely ill-mannered, so divisive, so uninhibited in appealing to racists and misogynists, so contemptuous of democratic institutions, so dismissive of the post-1945 world security order, and with an economic platform bound to push his supporters into poverty while enriching his mates in the oligarchy.

In part that’s because it’s difficult to understand the appeal of the authoritarian populist. “Liberals trying to understand Trump’s support might have to look more to the passions than to reason”, writes Watson. He goes on to write:

The autocrat offers to take care of things. He needn’t say how, only that he will do what his followers want done, what is necessary, what is just. His followers give themselves up to his promise. He’ll take care of their needs and (in the other meaning of the term) take care of their enemies: the freeloaders who take real Americans for mugs; the liberal elites who take them for granted; the immigrants who are taking their jobs, their hotel rooms, their safety, even their lives. Their country. The autocrat who derides identity politics practises it in an extreme form.

Further on he writes:

MAGA is 70 million of them handing up their sovereignty to Trump and the movement for the feelings of power that American democracy has denied them. They have been, as it were, dethroned. When Trump abuses and demeans his opponents and all those who are not with the movement, when he dehumanises refugees and immigrants, the MAGA folk feel the power flow through them. Fascism makes the weak feel strong. Those MAGA hats arm them with the power of belonging, grant coherence to their grievances and assert their status as the real Americans. They cry freedom because at last they are safe from it.

If you have read Watson’s essay as a flawed prediction of the outcome of America’s election, it’s worth reading it again as description of the president-elect’s platform.

You can hear Don Watson reflecting on his Quarterly Essay on the ABC’s Year that made me program last Sunday. The episode is mainly about his writings, but it’s also about Trump’s success. The roots of Trump’s victory are very old, he says. Trump has been able to excite people’s racist and misogynistic feelings, and has won over the working class.

His Quarterly Essay raised the possibility of America becoming embroiled in conflict if Trump lost. Because they have won this time, Trump’s followers, who were the instigators of violence in 2020, have nothing to be angry about, but Watson wonders if others will rise to protest against Trump’s authoritarianism.

Arthur Sinodinos, Geraldine Doogue, Jonathon Swan, Carrington Clarke

Is Trump serious about leading America to fascism?

Australians are probably more shocked by Trump’s success than Americans, because we have a biased view of America.

The Americans we meet in Australia, by definition, are those who travel abroad, but only around 45 percent of Americans have a passport, and that 45 percent is concentrated in the west and northeast states – the blue states. By contrast only three percent of people in Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi hold passports. When we travel to America for business, education or recreation we fly over the inland: many Americans contemptuously refer to the “flyover states”. If we are driving through inland America we go from one urban centre to another, never taking the freeway exits that lead to Trump’s America.

Maybe that’s why most Australian journalists are tending to look on the bright side of the election. That Trump wouldn’t be the first politician to be more aggressive in campaign mode than in governing is a common interpretation, and surely he will be constrained by moderating forces.

That may be wishful thinking. On election night Arthur Sinodinos, former ambassador to Washington during Trump’s first term, said that Trump was serious about his promises. Similarly the ABC’s Emily Clark, writing from Washington, takes his promises seriously in her post about how Trump plans to re-shape America. On last week’s Global Roaming program, Geraldine Doogue and Hamish Macdonald have an extended interview with Australian Jonathan Swan, a reporter for the New York Times, known for his Emmy-award winning interview with Trump when he was president: How will Trump rule now? (36 minutes).

As a “shocked and rattled” Geraldine Doogue says on that program, Trump has a decisive mandate, and the America we know may be gone. She identifies Trump’s success as a successful revolt of the working class. (Isn’t that what the left used to try to achieve?)

Swan’s interview has three themes. One is about the Trump campaign. It was professional and data-driven. We shouldn’t be fooled by what we saw on TV – an angry old man surrounded by hillbillies in red baseball caps, incoherently ranting about immigrants eating cats. Behind the showmanship was a well-targeted campaign. The second theme is that we should take his promises seriously: he will move on deportations, even if it is difficult, and he will raise tariffs. The third theme is about the ease with which he will implement his program: he is more experienced than he was 8 years ago; he is more confident; he has his own Supreme Court and a friendlier Congress; and after he has sacked enough public servants he will be surrounded by his own people.

Above all he has a mandate. He has won the popular vote; he didn’t just scrape through. The near-death experience of surviving an assassination attempt has boosted his and his disciples’ belief that he has some divine purpose to lead America to a golden age. And, unlike the situation in 2016, people knew Trump: they knew about his insurrection and his convictions. With Donald Trump's election win, America knew exactly who it was voting for writes the ABC’s Carrington Clarke.

Similarly Trump voters got what they wanted writes Tom Nichols in The Atlantic. They had no interest in a set of policies that may see their conditions improve: that’s what the Democrats were offering. Rather “a majority of American voters chose Trump because they wanted what he was selling: a nonstop reality show of rage and resentment. … Trump voters never cared about policies, and he rarely gave them any”. In fact before the election Nichols pointed out that Trump’s depravity would not cost him the election. “Many Americans know exactly who Trump is, and they like it”.

In time his supporters will be disillusioned: “Those who expect that Donald Trump will hurt others, and not them, are likely to be unpleasantly surprised”, writes Nichols.

Maybe, as the conventional wisdom asserts, the pendulum will swing back, and the Democrats will re-take the presidency in 2028. But such a correction is not guaranteed. Trump has two years at least (before the midterms) to change voting systems to his advantage, to silence voices of dissent, to use social media as a government propaganda channel, and to re-fashion the Department of Justice into an arm of executive government.

Nichols is author of the 2021 book: Our own worst enemy: The assault from within on modern democracy.

Kos Samaras

Kos Samaras, in his Financial Review article – The working class isn’t woke. That’s a huge problem for the left– asks if Trump’s victory points to a broader problem for social-democrat parties the world over.

For those without a subscription the Financial Review’s paywall sometimes lets outsiders in on a once-off basis. If you cannot get into it, the gist of Samaras’ article is that the decline of centre-left parties in democratic countries relates to their spilt constituencies – liberals concerned with social justice and long-term issues such as climate change, and low-income workers concerned with job insecurity, rising prices, declining life expectancy, and stagnant wages.

Populist parties on the right have made significant inroads into that latter constituency, which was once the core of support for social-democratic parties.

That’s not a new idea, but it’s worth asking if it really is so hard for the centre-left to serve both constituencies at the same time. After all, those parties’ engagement with issues of social justice arose from concerns for the lot of the working-class. Marxists and social democrats alike strived to raise class consciousness to help workers understand and combat the methods used by the right to get them to vote against their class interests.

There does not seem to be any basic ideological conflict between the two groups: both strive for a fairer society in which the benefits of economic activity can be shared more equitably.

Maybe reconnection of the parties with their constituencies lies in more mundane measures, such as making party membership more appealing.

Samaras notes that parties of the left are struggling to “pivot back to the economic concerns of working-class voters because they are increasingly made up of activists, staff, and representatives from urban, middle-class backgrounds”. That shouldn’t be too hard to deal with. Shift those staff out of Washington, Berlin, Canberra and other urban centres to where the voters live.

In Australia that means giving more power and delegated responsibility to public servants in all regions, as the Coombs Commission on Australian Government Administration recommended 50 years ago. It may mean re-establishing the Commonwealth Employment Service staffed by public servants rotated between Canberra, state capitals, and other regions. It could involve making more use of information technology to ensure that everyone, wherever they live, can make personal contact with a government employee.

That would put an end to the Trumpian idea of a “deep state” conspiracy, and it could end the phenomenon, observed by Samaras, of voter dissatisfaction with social-democrat parties falling away with distance from state capitals.