Other economics

Inflation in Australia is dangerously low

The Consumer Price Index for the three months to September, released on Wednesday, shows that the CPI over those months rose by 0.2 percent. That’s an annual rate of just over 0.8 percent. The seasonally-adjusted change in the CPI over those three months, was only 0.1 percent, or just over 0.4 percent annualized.

These are the best estimates of the present rate of CPI inflation. In fact we have no way of knowing what inflation is now; all we can go on are figures covering some recent period.

But that is not the way the media reports the CPI. The common story, including the way the ABC reports on ABS CPI data, is to assert that CPI inflation is 2.8 percent. In fact, when the Reserve Bank reports on Melbourne Cup Day next week, it will almost certainly say that CPI inflation is 2.8 percent.

In fact that 2.8 percent is the change in the CPI from September 2023 to September 2024. No one, including the Reserve Bank, has any authority to use that figure as an indicator of what inflation is now. As the Australia Institute’s Richard Denniss says on a Radio National interview – What new inflation figures mean for interest rates – the RBA should pay less attention to figures that lie behind us and pay more attention to the economy’s needs.

That emphasis on timing may appear to be nitpicking, but it’s an important point in a period when CPI inflation is falling. If inflation were kicking along at about the same rate, year-to-year, it would be OK to use the rate over the last twelve months as a rough indicator of the current rate, but not now when some of those price rises are behind us.

As an analogy, imagine you have driven the 300 km from Sydney to Canberra, keeping within the 110 kph speed limit on the Hume and Federal freeways. You have arrived in Canberra’s outer suburbs, keeping within the 50 kph suburban speed limit. But a cop pulls you up, and insists on seeing your car’s computer, which reveals that on your trip your average speed has been 90 kph, and books you for speeding. You would be rather pissed off, and all Australians should be pissed off at the way the media and the Reserve Bank use dated data to report inflation. It’s deceitful, even if it’s not intentional.

Also, because this past 12-month measure overstates present inflation, it feeds into inflationary expectations, and sustains the narrative that we are in some ongoing “cost-of-living crisis” with high inflation, when in reality we are seeing a sustained reduction in the inflation the present government inherited from its predecessor.

Electricity and rent

Some naysayers, determined to put the government in the worst possible light, will point out that the low CPI rise in the September quarter results from a fall in the electricity index, pulled down by various government rebates.

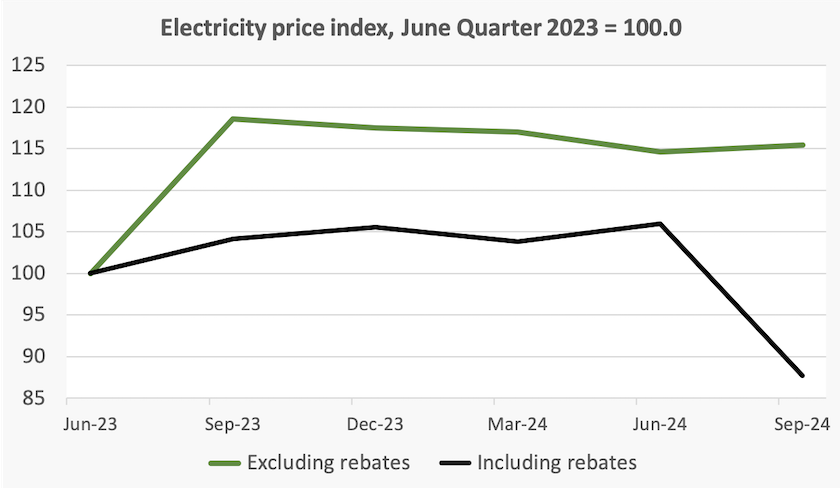

The graph below (which also appears in the ABS site), shows the electricity price index over the last 15 months, with the rebates (black line) and without the rebates (green line). The index typically rises in the September quarter, reflecting annual changes in the regulated default market offer. That is clear in the steep rise in the September 2023 quarter, where the 19 percent rise was reduced to a 4 percent rise because of the rebates in the year.

It is notable that this year the pre-rebate electricity price has not risen: in fact it is down by about 3 percent over the year, and it rose by less than 1 percent in the last quarter. There is nothing in these figures to support the Coalition’s claim that electricity price rises result from an increasing penetration of renewable energy. In reality it is just the opposite. If successive Coalition governments from 2013 to 2022 had pursued a responsible energy policy without waging a war on renewable energy we would not be needing those rebates.

Also notable in the CPI figures is that the inflation in rents is coming down. It’s still too high, at 1.6 percent in the quarter (6.6 percent annualized), but that’s down from 2.5 percent at its peak last year (10.4 percent annualized).

The ABC’s Ian Verrender explains more about specific causes of Australia’s recent bout of inflation, rebutting the simple economic model that seems to be driving the RBA’s interest-rate decisions: Who is to blame for Australia's inflation problem and stubbornly high interest rates? He concludes:

While economists and the Reserve Bank talk about "sticky, homegrown inflation", the problem isn't because people suddenly have a craving for a hospital stay. It's because the increased demand from a growing population hasn't been matched with a corresponding lift in the amount of service providers.

You could raise interest rates to 20 per cent if you like. But that won't fix the problem.

The RBA, when it meets next week, will probably focus on what it calls the “trimmed mean” CPI, which rose by 0.8 percent over the quarter (annualized 3.2 percent), and will probably use that to argue that it has to keep rates high. Writing in The Conversation John Hawkins of the University of Canberra explains how the RBA will probably interpret the CPI data: Inflation is sinking ever lower. Now that it’s official what’s the RBA going to do?.

That’s about another problem in the RBA’s way of doing its work, about which there will undoubtedly be a great deal of comment after it announces its decision.

All you need to know about money, taxation and government spending

Fred Schilling has brought to our attention five short YouTube clips by Peter Murphy of Sheffield University:

What is the real reason why we pay tax? It’s not the reason you think.

The government can never run out of money. No it really can’t.

Government surpluses don’t create cash piles waiting to be spent. A demolition of the idea that a budget surplus is an unmitigated good.

There is no such thing as taxpayers’ economy. A neat explanation of how governments create money.

Modern monetary theory is not a policy. It does not advocate a particular policy direction; rather it’s an explanation of how a fiat currency works.

The term “Modern Monetary Theory” is often misunderstood. People accuse its proponents of inciting economic recklessness and promoting inflationary policies of countries like Venezuela. But in fact, as Murphy describes, it’s an explanation of how public revenue works, in established terms of double-entry bookkeeping. Most importantly Murphy emphasizes that in an economy money is the “enabler” of economic activity: it is not to be confused with the economy’s real resources. And he explains the fallacy, often voiced by right-wing and neoliberal politicians, of likening public finance to private finance such as applies to businesses and households.

My own comment on Modern Monetary theory is that it’s all in line with basic, orthodox economics. (Why do they call it “modern” and scare the horses?) MMT proponents try to get the bean counters in treasury departments to think of real resources, rather than fiscal aggregates. Before deciding to spend money on housing, for example, governments should find out if there are enough tradespeople: if there are too few tradespeople available for employment there will be inflation. At the same time there will be other areas of the economy with underutilized resources, where failure to spend results in an opportunity cost.

That shouldn’t be radical, but it has to be stated because successive Commonwealth governments of all persuasions pretend that fiscal management is the be-all-and-end-all of economic management, when it’s really only the bookkeeping.

Illustrating this dysfunctional obsession there have just been two elections, in the ACT and Queensland, in which the government and opposition have been subject to the task of providing fiscal costs of their policies. Voters would be far better informed if political parties had to account for the economic costs of their policies in terms of demands on real resources.

Tobacco economics

Smoking is an expensive pastime. With a typical pack costing about $40, the addicted smoker, getting through a 20-pack a day, spends about $15 000 a year to support the habit. Pastimes like skiing in Switzerland or competing in the Sydney-Hobart yacht race would be cheaper to sustain – with better health consequences.

It’s hardly surprising that a black market has developed, even though cigarettes, in comparison with other hard drugs, are bulky and difficult to conceal.

The extent of that black market is revealed in government finance figures: last year the government expected to collect $12.85 billion in tobacco excise, but by the time the budget was presented they had revised that down to $10.50 billion.

In a post on the ABC website, Jane Norman explains that two Queensland Coalition MPs – Llew O’Brien and Warren Entsch – have called for the government to cut tobacco excise, in order to remove the returns for black marketers, to reduce the burden on law-enforcement authorities, and to protect genuine retailers .

Norman’s post goes through the politics and economics of tobacco excise, pointing out, unsurprisingly, that the Cancer Council has no desire to see the excise rate dropped.

One has to question the motives of these two politicians. Both represent rural electorates. Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reveals that older men in non-metropolitan regions are the highest smokers. As for tobacconists, it’s hard to shed a tear for those who try to make a living by selling lethal addictive drugs: they could turn their skills in retailing towards something useful. And it’s strange to hear politicians from a party that’s always had a tough-on-drugs policy become so lenient.