Housing

Coalition out, Labor up

The Coalition is going for urban sprawl, while the government is more inclined to increasing the density of our existing cities. Building out vs building up is the simplified presentation of the difference.

Sunlit plains extended

Both the government and the Coalition see investment in housing infrastructure as necessary to boost supply, but there the similarity ends. For the Coalition that infrastructure would be in further urban sprawl, and the Coalition has two other proposals aimed at making houses in those new developments more immediately affordable, while imposing long-term costs on buyers.

One is to allow people to dip into their superannuation balances to fund a deposit, up to 40 percent of their balance or $50 000. The long-term consequences are clear: $10 000 in the superannuation account of a 25-year old will be worth about $100 000 when he or she is 65.

The other proposal is to freeze changes to building codes, including those that relate to energy efficiency standards in new housing. In exchange for slightly less expensive housing, home buyers would be saddled with years of discomfort and higher energy costs.

A general assessment of the Coalition’s policies is in Karen Barlow’s Saturday Paper article: The Sukkar interview: How the Coalition plans to fix housing.

Some property developers have welcomed the Coalition’s policy, because it allows them to continue with their established business models, but after initially seeming to support the Coalition’s policy, the Property Council has backed away from supporting a freeze in building codes.

South Yarra transformed

To put the Coalition’s policy in the simplest ethical terms, it offers the prospect of a lower purchase price, while imposing a long stream of costs from the day house buyers turn the key in the door. These include higher energy bills (someone has to pay for all that nuclear power), longer commuting costs (probably requiring the need to own and run a second car), the social isolation of suburbia, and an impoverished retirement. And that’s before considering the demand-side boost to housing prices by allowing people to access their superannuation funds. It’s a lousy deal pandering to people’s weakness in choosing immediate gratification over long-term benefits.

The Guardian’s Sarah Basford Canales outlines the economics and politics of the Coalition’s proposal in her article Pocock condemns “seriously regressive” elements of Dutton’s $5bn plan to tackle housing crisis.

The ABC’s Tom Crowley points out that sate governments are already moving towards densification, in line with the Commonwealth’s policy, but it’s electorally tricky for them because NIMBYism is one of the strongest imaginable political forces: The housing fight has made it to the streets. Now for the hard part. Getting down to the specifics the ABC covers the Victorian government’s announcement for 50 higher-density housing zones in Melbourne. Toorak, Hawthorn and Glenferrie are all on the list.

Core Logic, in its post Making sense of housing policy proposals, makes the point that up to the 1980s state governments used to fund local infrastructure for housing development. Since then local infrastructure has been built into house prices, with a profit margin for developers.

Perhaps it would be fair public policy if funding for housing infrastructure were to be raised by higher taxes on the baby-boomers, most of whom bought houses before 1980, enjoying the contributions of earlier taxpayers who financed their drains, roads and sewers.

The attraction of easy but counterproductive policies

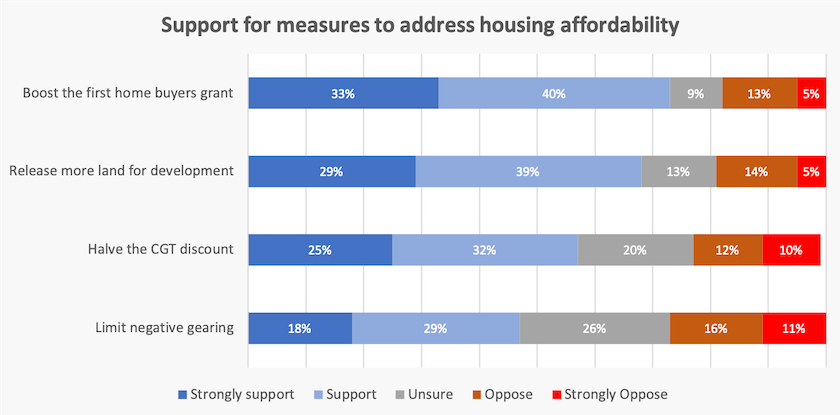

The political economy of housing policy is illustrated in an article by the ABC’s Tom Crowley, reporting on a poll of four possible measures to improve housing affordability.

Responses are shown in the chart below,

Boosting the home buyers’ grant is the most popular but also the most counterproductive policy.

Releasing land for development, the second-most popular response, shows how hooked we are on the 0.1-hectare block in suburbia: have people really thought what ever-increasing sprawl would look like – Los Angeles without the convenience of that city’s freeways.

Halving the capital gains discount is a perennial popular among policy advocates who don’t understand how capital gains and inflation work. Unless the assessment of capital gains is discounted for inflation, any such reduction on the discount will add to the already existing perverse incentives that reward speculation, including housing speculation, over long-term investment. The most economically efficient and fairest reform is to tax capital gains at 100 percent, with allowance for inflation, as was the case before 1999 when the Howard government, yielding to the finance lobby, brought in the present system.

Limiting negative gearing makes sense in equity and economic efficiency, particularly in a situation where a small number of property investors control a large chunk of the rental market. The 80 percent of Australian taxpayers who don’t own negatively-geared properties, including those who have made more responsible investments than housing speculation, have been subsidising these so-called “investors” for 25 years. As Tarric Brooker of news.com.au points out, the most likely group to have negatively-geared property are people with incomes between $500 000 and $1 000 000.

But the government, fearful of scare campaigns, has walked away from reforming negative gearing. That makes some sense fiscally, because as time has gone by and as people have paid down their loans to buy property, the taxation benefits of negative gearing have been lost. Now we are in a situation where people have less spare cash to invest, state governments have set disincentives for property speculation, and property prices have fallen in some markets, all meaning that property has become less attractive for small investors. As for those with 20 or more properties, their day will come: be on the lookout for Porsches and BMWs for sale at distress prices.

One reform that gets the occasional mention is the abolition of stamp duty and its replacement with a land tax, as advocated by the Business Council of Australia who join with a long line of economists and policy experts who have been calling for such a reform. It would not only make housing more affordable for first-home buyers, but it would also make it less costly for people to shift to housing that fits their needs over their lifetimes and it would help in allocating housing space more efficiently. It’s politically difficult, because the cost would fall on established home owners (who one day will regret their opposition to reform when they try to tree-change or downsize).