Three elections, common patterns

The ACT – Labor loses ground but no joy for the Liberals or Greens

ACT elections don’t raise much interest nationally. Even in Canberra, were it not for the proliferation of corflutes along every major road, even locals might not be aware when the territory is going to the polls.

Capital choices

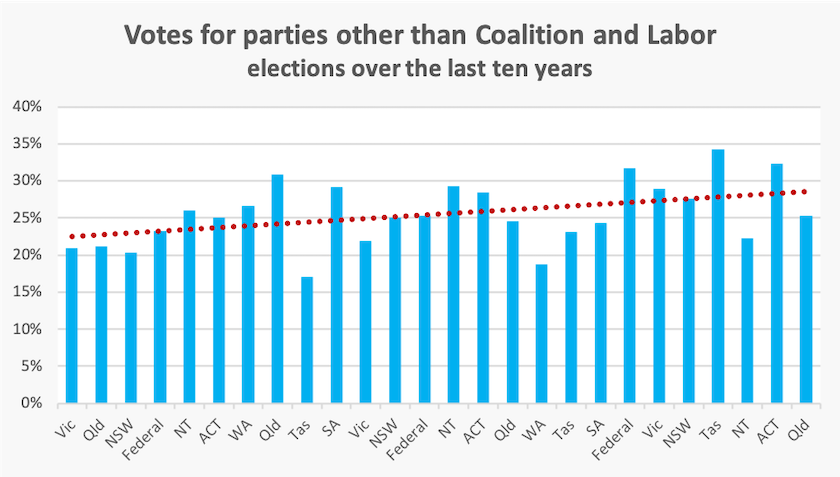

Although the rest of Australia tends to consider the ACT as some left-wing haven, out of step with the rest of the country, the outcomes of the territory’s election on October 19 election were in line with national trends, particularly the loss in support for established parties.

Labor won a seventh consecutive term in office. As in all but one of those six previous elections, it will be governing in minority, with 10 seats in the 25-member Assembly, while the Liberals have 9 seats. The only change in party representation is that the Greens now hold 4 seats, down from 6 seats, their places having been taken by 2 newly-elected independents.

This outcome arises from the ACT’s Hare Clark electoral system, which is similar to Tasmania’s. The ACT has five electorates, each electing five members on a proportional representation system (described in James Glenday’s article Is ACT Labor becoming Canberra’s “forever government”? ). In order to win 13 seats, the minimum for majority government, a party would have to win 3 out of the 5 places in at least 3 electorates. That’s a big hurdle.

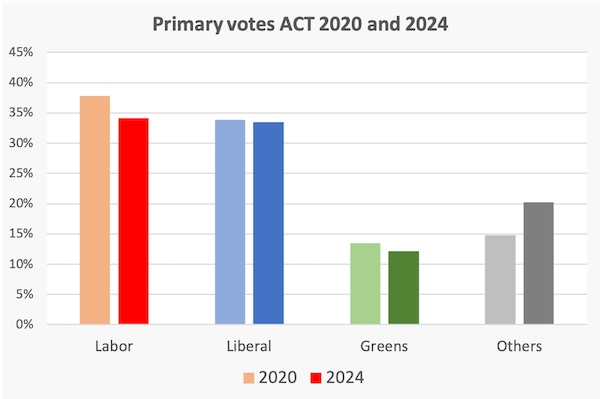

Behind that minor change in representation there has been a significant shift in voting pattern, which can be found on Antony Green’s election website, summarized in the graph below.

All three established parties lost support: Labor’s vote is down 3.7 percent; Liberal’s vote is down 0.4 percent; and the Greens’ vote is down 1.3 percent. Balancing these losses, support for independents is up 5.4 percent.

Different electorates showed very different swings. The ACT has two electorates, Kurrajong and Murrumbidgee, just to the north and south of Lake Burley Griffin. Kurrajong is a prosperous, established electorate, where support for the Liberals is low – 24 percent. Kurrajong and the eastern part of Murrumbidgee are the equivalent of what in Melbourne and Sydney would be called Teal territory.

In both electorates all three parties lost support. The swing away from the Greens was particularly strong in Kurrajong, the more densely urbanized of these two electorates. Each elected one of the territory’s two new independents, replacing sitting Greens.

In the Brindabella electorate, 20 km to the south of the city in its own valley, the story is different. There was a 6.9 percent swing away from Labor and a 4.7 percent swing towards the Liberals.

Brindabella, in many regards, is characteristic of outer suburban regions in the rest of the Australia. It was developed in the late 1980s, and is now ageing. Nationally, the Liberal Party would be encouraged by this result, particularly because people in this electorate probably don’t have high mortgage debt and therefore won’t feel better off when interest rates start to come down.

At the other end of Canberra, however, in the northern reaches, the story is different again. The suburbs are newer, and people are therefore likely to be carrying comparatively high mortgage debt, but there was no swing to the Liberals in these electorates.

This contrast between two outer-suburban electorates does not align with the idea that interest on mortgage debt is the main driver of voters’ discontent. Age and ethnicity, for example, may be the main drivers of these differences.

These results tend to confirm general impressions of national voting trends. There is little chance that the Liberals will be able to take back prosperous inner-city seats. They may do well in some outer urban regions, but not all such regions are the same. And surely the Greens will feel chastened by their loss of two seats: the people of Canberra have had a ringside seat watching their childish behaviour in the federal Senate and have been highly impressed by their independent Senator David Pocock..

But why have these results put Labor back in place?

As the numbers firmed, the idea that Labor would form government was unquestioned. Antony Green, renowned for his caution in calling elections, said there was no viable path for the Liberals, led by Elizabeth Lee, to form government.

But why not? At that stage the Liberals had 9 seats, the Greens had 3, and the 2 independents would probably describe themselves as progressive. An observer presented with these numbers, making no ideological assumptions, could imagine a Liberal government with 9 seats, and up to 6 others ready to join a coalition or at least to guarantee confidence.

Fanciful? Such coalitions are common in European democracies, particularly in Austria and Germany.

The fact that it is so unimaginable in Australia says something about our parties, particularly the Liberal Party, which is so solidly in the hands of the extreme right. Elizabeth Lee herself would be described as a “moderate”, but on the backbench of the ACT party are hard right-wingers, one of whom is has successfully challenged Lee for the leadership. The ACT Liberal Party could be heading for the same strife that is tearing the party apart in most southern states.

Queensland – a win for the LNP. Now for the hard policies

The general media interpretation of the Queensland election is that Labor did surprisingly well, because it didn’t suffer a catastrophic loss as had been predicted in some of the polls.

That probably says more about opinion polls than it does about voter sentiment. The media love portents about political catastrophes, particularly if they relate to bad news for the Labor Party. But as is revealed in the difference between pre-poll votes and votes made on the election day, there does seem to have been an improvement in support for the Labor government as polling day got closer.

In fact this was a bad defeat for the Labor government. Although its primary vote, at 32.7 percent, was almost the same as its national vote at the 2022 federal election (32.6 percent), Labor had little support from preferences in the state election. The Green vote was down, there were no strong “Teal“ independents, the LNP’s primary vote was 42 percent, and there was an 8 percent vote for One Nation, effectively giving the right a 50 percent base.

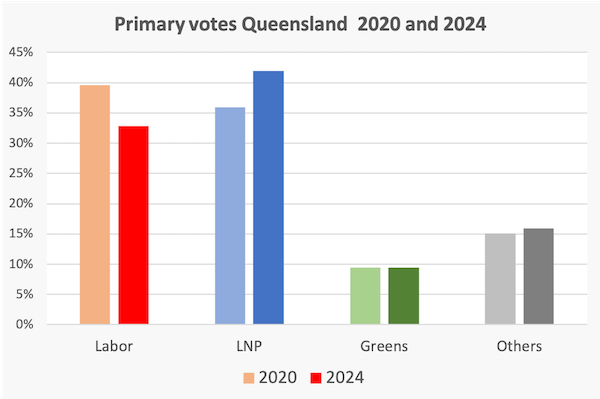

The two-party outcome therefore was 54:46, a 7 percent TPP swing against the Labor government. The primary votes are shown on the graph below and full details are on Antony Green’s election website.

Those are state-wide figures. What stands out is that the primary vote swing against Labor (6.8 percent state-wide) became stronger the further one got from the Brisbane CBD, and Labor was defeated in large coastal cities that were once Labor strongholds.

The ABC’s Casey Briggs appearing on the Insiders’ program on Sunday morning, gave a breakdown of the broad regional swing against Labor:

- 6 percent in the Brisbane City Council region (much larger than other city LGAs)

- 8 percent in the outer suburbs

- 10 percent in the rest of Queensland.

Casey Briggs reported that in Queensland apart from Brisbane Labor’s primary vote was only 26 percent, while the LNP’s vote was 44 percent and the One Nation vote was 12 percent. That’s a hard-right base of 56 percent in a region that includes substantial cities with populations over 100 000, including Townsville, Cairns and Toowoomba. It’s not just a rural-urban divide: electorally these cities are not scaled-down versions of Brisbane, where Labor held almost all its seats.

Those are some of the basic hard facts on the election. As is generally the case there are plenty of experts on hand offering explanations for the outcome. Two of the more detached are Paul Williams of Griffith University, interviewed on Radio National (15 minutes), and Patricia Karvelas, who offered several insights on The Insiders’ program, linked above.

Williams mentioned the main issues in the election – youth crime, cost-of-living, housing, hospital ramping and abortion – all but the last helping explain the swing against the government.

Youth crime, which was also a major issue in the Northern Territory election, is one issue where the state government clearly bears some responsibility for the voter reaction. As in the Northern Territory it allowed the issue in the public mind to become one where the government had sacrificed public safety to the interests of uncontrolled children. Solutions that met both needs were not in place.

The Crisafulli government is under great pressure to implement its “adult crime, adult time” policy, and to lower the age of criminal responsibility, particularly as the summer wave of youth crime approaches. Locking up offenders is an easy solution, with immediate effects, but if it is within the criminal justice system, its medium and long-term costs are huge, in terms of fiscal outlays, community safety, and social division. This problem isn’t going to go away.

Cost-of-living, housing, and hospital ramping are issues of concern to many Australians, although the so-called “cost of living crisis” is actually a problem of inequality: most Australians are doing very well for themselves. They are issues over which state governments have little control. Nor does the Commonwealth government have much control in the short-term. They all relate to many years of poor public policy at the Commonwealth level – years in which successive governments, mainly Coalition governments, neglected reforms to taxation and economic structure, allowing productivity to fall and inequality to widen.

Abortion became an issue late in the campaign, and it may be a reason why the polls tightened during the campaign, and why pre-poll votes were much less favourable to the government than votes lodged on election day. The government allowed a scare campaign to develop (“Risk to women’s reproductive rights”), but as Karvelas points out, there is some substance to the idea that Coalition parties are likely to pursue a toughening of laws on abortion, and Crisafulli has prevaricated on the issue.

Abortion seems to have become an active issue because of hard-line proposals by Katter Party politicians on abortion and on corporal punishment, which came to voters’ attention late in the campaign. Premier Crisafulli msut be relieved that he has scraped through with a majority, rather than having to rely on the Katter Party’s elected members. But the issue won’t necessarily go away, because there are plenty of hard-liners in the LNP.

Closely-related is the question of early voting and the span of political campaigns, particularly in the farcical situation where parties’ election costings are published when half or more of the electorate has voted. In a democracy all parties should have an opportunity to put their proposals to the electors, but we have allowed the development of an electoral system which means that many people, a majority in some electorates, cast their votes before they have had a chance to be fully informed.

One notable feature of this election, missed by most commentators, is that Queenslanders reverted to a traditional two-party vote, shown in the graph below. That could be a result of the long period for pre-poll voting, because small parties and independents have fewer resources to man pre-poll voting centres.

Karvelas mentions the poor outcome for the Greens, as does the ABC’s Elizabeth Cramsie: Shock result for Queensland Greens. (3 minutes). Kos Samaras suggests that their strategy of cooperating with the Coalition to wedge Labor is failing.

Nuclear power hardly featured in the election campaign, but it has become an issue because of a conflict between the federal and state Coalition parties. Th ABC’s Tom Lowrey reports on these tensions: Coalition confident new Queensland government will back nuclear power. Writing in The Age – Lessons from the Queensland election that should worry Peter Dutton – David Crowe explains how the nuclear issue will become a difficult issue for the federal Coalition, because two of its reactors would be located in Queensland.

Finally there is the possibility that the LNP did well because in its campaign it was politically moderate. The commentariat said that Crisafulli presented a “small target” – a rather meaningless way to describe any campaign. A more likely explanation is that Crisafulli was not shackled by association with the corruption of the Bjelke-Petersen government or the right-wing extremism of the Campbell Newman government.

It’s unfortunate that in all elections there generally develops a common narrative, ascribing the outcome to one dominant cause – a narrative that disrespects the complexities of a democracy in which the old economic class divisions no longer hold sway. Sometimes studies by university schools of public policy find that those hastily-agreed narratives are just plain wrong, as was the case with the common idea that Labor’s proposals on housing taxes cost it the 2019 election.

Much of the public discussion has been about the implications for the federal election next year. It’s been a big swing against Labor, particularly in outer suburbs which have been the party’s main source of support. But there are particular Queensland factors. Karvelas raises the “it’s time” factor: Australians don’t often give governments a fourth term in office. Youth crime is an issue manly north of the Tropic of Capricorn: it is far less an issue in the rest of Australia.

In any event Labor has little to lose in Queensland: its primary vote in 2022 federal election was only 27 percent. It holds only 5 seats in Queensland, 4 of which are in the Brisbane region.

The state election was a victory for the LNP, a party dominated by and representing a non-urban constituency. The hard work of fighting a federal campaign from opposition next year will be up to the Liberal Party, which holds only 25 seats in the 151-member House of Representatives.

The blue waters of Pittwater turn teal

If Bob Menzies were to turn up in Australia in 2024, he would almost certainly identify Sydney’s northern beaches as Liberal Party heartland. They stretch out on a peninsula from Mona Vale to Palm Beach, with the Pacific Ocean on one side and the Ku-ring-gai National Park and Pittwater on the other. This peninsula roughly defines the state electorate of Pittwater, which in state and federal elections has traditionally come in solidly for the Liberal Party – usually 15 percent or more above the state or federal average.

In a state by-election on October 19, the independent Jacqui Scruby won the seat from Liberal candidate Georgia Ryburn, a by-election necessitated by the resignation of the previous Liberal Party member. She won the seat convincingly with a 55 percent primary vote. There was no Labor candidate.

It’s a classic “Teal” story. Scruby is a sustainability consultant and former environmental lawyer, who has previously worked as an adviser for federal independent MPs Zali Steggall and Sophie Scamps (whose federal electorate of MacKellar includes the state electorate of Pittwater). Scruby contested the seat in the 2023 state election but was narrowly defeated by pre-poll votes.