Public ideas

Always look a gift horse in the mouth

The actual proverb is “Never look a gift horse in the mouth”, generally interpreted as advice not to criticize something good on offer.

The counter to that proverb is Milton Friedman’s advice that “There’s no such thing as a free lunch” – one of Malcolm Fraser’s favourite aphorisms.

Friedman would be gratified to know that people seem to have heeded his advice. That is confirmed in a study reported by Andrew Vonasch of the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, in a Conversation contribution Too good to be true? New study shows people reject freebies and cheap deals for fear of hidden costs.

The research Vonasch and his partners have undertaken finds that when people are offered what look like reasonable discounts for goods, they take them up: that’s in line with Economics 1, Lecture 1. But when price offers or discounts are extremely generous, people’s suspicions set in: there must surely be a hidden cost somewhere. The same applies to those (tautological) offers of “free gifts” associated with purchases. If the gift is too lavish, we walk away from the offer, unless there is some plausible reason for the generosity (slightly damaged stock, for example).

The same finding applies to job offers. If we are offered a job with what looks like an unreasonably high salary, we start to think it may involve unreasonably high workload, some danger, or a requirement to compromise our moral principles.

This research is a useful contribution to behavioural economics. Like all findings in behavioural economics, they apply to a majority of people: there are still people who fall for teaser offers, get-rich-quick programs, and too-good-to-be-true scams. Companies selling ongoing services, such as insurance policies and newspaper subscriptions, still hope they can trick enough people with cheap introductory offers.

A race to enlightened sanity

If you spend any time in the USA, sooner or later you will be called on to fill out a form on which you are asked to classify yourself to a “race”. Those who realize that the concept of “race” has no scientific meaning will probably write “human”, or if they believe it has some residual meaning will probably write “mongrel”.

But Americans take race seriously. Kamala Harris, we learn, is Black – note the capital B – even though her skin colour looks much the same as most other Americans’. Donald Trump is white, even though his skin is a pinkish brown: he shows no signs of anaemia.

It’s all rather confusing, particularly in a country whose founding ideas can be traced to the Enlightenment. But then Jefferson, Hamilton and all that mob had a few difficulties with the Enlightenment, because it was difficult to reconcile Enlightenment values with slavery. Enlightenment lite perhaps.

Americans have been struggling with the ideas of “race” for some time. The Civil War, which was meant to settle the matter, effectively carried on until 1964 with the passing of the Civil Rights Act, 103 years after it started – and they’re still grappling with its aftermath. They find it too hard to come to grips with the consequences of slavery and systemic discrimination, because that may get them thinking about dangerous Marxist ideas about enduring economic disparities and even class. It’s safer to stick to “race” and its variants, such as “people of color”.

To guide us through this confusion – or perhaps to show how complicated it all is – Waleed Aly and Scott Stephens discuss the idea of “race”, first with each other and then with their guest Coleman Hughes, on The Minefield: Coleman Hughes, “colourblindness”, and the contentious politics of race.

The initial discussion between Aly and Stevens is about the Voice and why it failed. They put forward the idea that while the proposition was simple (provision of a voice to the original owners and occupiers of this land), during the campaign it became mischaracterized as something much bigger. In the public mind it came to be seen as a means of making amends for past wrongs.

They attribute this mischaracterization to the way the campaign was infected by an American discourse about race, even the idea of critical race theory (CRT). The CRT frame establishes an “unanswerable” conflict, because racial disadvantage, and advantage, are set in immutable structures. It’s not a very attractive concept to people deciding how to vote in a referendum.

Perhaps they’re stretching the point. CRT didn’t actually get much airing in the campaign, and most Australians who have taken the trouble to study CRT find it to be junk political theory, because it is incapable of being subject to any test that may confirm or falsify it.

Aly and Stevens are adept at stimulating ideas, and at introducing different perspectives to public policy issues. Their idea that the Voice failed because it became in the public mind something much bigger than it actually was is a valuable insight. But this idea didn’t just drift in as their passive-voice statements suggest. There was agency: it was Peter Dutton who decided to make it about “race” rather than indigeneity, a representation that paved the way for a scare campaign – the idea that “they’re coming to take your land”, and that indigenous Australians would enjoy privileges denied to other Australians.

Hughes comes in around the middle of the session. His perspective is American, and in a style reminiscent of Martin Luther King he argues for a classic liberal idea of colour-blindness. He is not opposed to special treatment for the disadvantaged in order to improve equality of opportunity, but any such treatment should be on the basis of hard socio-economic criteria, not on skin colour or “race”.

His discussion about guilt, particularly the idea that in “western” societies people feel pressured to make amends for the sins of past generations, is most insightful.

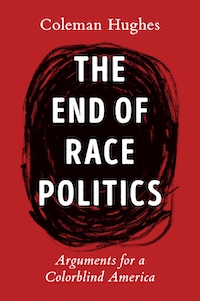

Hughes is the author of The end of race politics: arguments for a colorblind America.

We may feel smug that although our ancestors, like in the US, took land from its original owners, we didn’t have a slave-based economy. (That is if we don’t regard kidnapping south sea islanders for forced labour in cane plantations as “slavery”.) Writing on the ABC website Annabel Crabb reminds us of our dark history of racial and ethnic discrimination: Punishing people because of their culture or background should be behind us. Yet it's a mistake Australia keeps making. We should not forget some of the vile accusations made against Chinese Australians during the Covid pandemic, for example.

She writes about the recent outbreak of anti-Semitism. Some assert that is unprecedented, but Crabb reminds us of the disgraceful instance of the Dunera incident, when Jews fleeing persecution in Austria and Germany were incarcerated as enemy aliens. She writes:

This impulsive fear and punishment of innocent people on the grounds of their appearance or garments or last name is a phenomenon you'd hope had disappeared along with polio, a relic of less enlightened times.

And yet. We did it again and again. We're still doing it