Politics

Noel Pearson and Bridget Archer on The Voice

Noel Pearson, who has spent years knocking on conservative doors to build support for The Voice, has called Dutton’s categorical hard position a Judas betrayal. Dutton has become “an undertaker preparing the grave to bury Uluru”.

Bridget Archer speaks for the few reasonable people remaining in the federal parliamentary Liberal Party. “We need to elevate this issue beyond divisive, nasty politics” she says. Dutton’s decision has tested her faith in the Liberal Party. She is no lone advocate: there are others in the Party supporting the Voice including the Premier of Tasmania. She does not see the Liberal Party in its present form as a credible alternative government.

The Aston by-election: no way for the Coalition to spin it

There are two main interpretations of the Aston by-election result.

The minority interpretation, held by most (but not all) of the 26 remaining Liberals in the House of Representatives, and by most in the National Party, is that the party just didn’t try hard enough to get its message across. We heard that on ABC Breakfast from Jason Wood, member for LaTrobe, who spent his eight minutes on air telling us how the results would have been so different if only the Party had sold Dutton and the party’s message more vigorously.

That has a ring of the philanderer spinning the “my wife doesn’t understand me” line.

The view that seems to be held by the majority of voters in Aston, by most independent journalists, and by many prominent members of Liberal Party who are speaking out – including Malcolm Turnbull and Simon Birmingham – is that the electorate really does understand what the party stands for, and doesn’t like it. It’s the political equivalent to the “your trouble is that your wife does understand you” response to the philanderer.

As if the gods are sending a confirmatory message to the parliamentary Liberal Party, Monday’s Newspoll was another shocker for Dutton and the federal Coalition.

There is little point in going through all the opinions, some informed, some simply gut feelings, on the reasons for the outcome and on what the Liberal Party needs to do now. But it is informative to look at some of the hard numbers, and to consider how the media has presented the by-election loss to the public.

The hard numbers expose a party that has lost its capacity to represent urban Australians. And the media response has been driven by journalists obsessed with Dutton, the “leader”, oblivious to the possibility that Australia is in an early stage of re-grouping of centre-right politics.

The hard numbers – a dismal message for the Liberals and the Coalition

It’s hard to find anything positive for the Liberal Party or the Coalition in the Aston by-election. The party’s primary vote is down by 4.4 percent, and its TPP vote by 6.5 percent. This is on top of a primary vote loss of 11.3 percent and a TPP loss of 7.3 per cent in the same seat in last year’s general election. That’s a cumulative loss of nearly 16 percent in primary vote, and 14 percent in TPP vote. Usually, after a strong swing in an election, there is some compensating swing in the subsequent election – a “regression to the mean” in statisticians’ terminology – but not this time. As with the general rule that the government does not win a seat from the opposition in a by-election, another political verity broken.

One might reasonably have expected that without Alan Tudge on the ballot paper the Liberal Party vote would have improved, and it could hardly have chosen a better candidate than Roshena Campbell. But that improvement didn’t happen.

In an interview on Insiders the morning after the election, Dutton’s main rationalization was to suggest that the Liberal Party has particular problems in Victoria, where the party’s vote has been falling since 1996 and where the state branch is particularly shambolic.

But it is wrong to see this as a Victorian problem. Rather, it’s about a problem the Liberals have in all Australia’s large cities.

In Melbourne the Liberal Party holds only 2 of the 22 seats that the Electoral Commission classifies as “Melbourne urban” on its map, but this lack of representation is not unique to Melbourne. The figures are proportionately the same in Perth (where the Coalition holds 1 seat out of 11) and in Adelaide (1 seat out of 7). The Coalition is doing a little better in Sydney (6 seats out of 25) and in Brisbane (the LNP holds 3 seats out of 10), but these are miserable figures for a highly urbanized country.

To collate these figures, in all four of our largest cities – Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth – the Coalition holds only 13 seats, while by contrast it holds 17 seats in Queensland outside Brisbane.[1] More generally there is a heavy Queensland over-representation in its ranks: Queensland has 20 percent of the nation’s population but 38 percent of Coalition members of the House of Representatives.

If the party’s strategists really believe that what happened last Saturday is a Victorian peculiarity they might try persuading the member for Cook to resign. With a 62.4:37.2 TPP margin in Morrison’s seat, surely they have enough up their sleeves to test the idea in a Sydney electorate that has much in common with Melbourne’s Aston.

These figures provide a snapshot of the Coalition’s position, but it takes a movie to show where the Coalition is heading. In last week’s roundup there was a table showing how the Coalition’s has lost support in 21 of the last 22 selections. The decline has been an average of 5 percent loss in primary vote in each successive election.

Some of that loss is demographic. The Coalition has always enjoyed strong support among older people, while younger people have been more attracted to left or progressive parties. For a long time that older cohort was replenishing itself: as Coalition voters died, people passing into middle and older ages would become more conservative and shift their support to the Coalition, but that transition seems to have stopped about ten years ago.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that this demographic trend is costing the Coalition party about two percent of the vote at each election.[2]

We don’t know why that replenishment has stopped. Perhaps people are still becoming more conservative as they age, but they don’t necessarily see the Coalition to be embracing conservative values – respect for the institutions of democracy, respect for learning, respect for truthfulness, and respect for those holding different opinions.

In view of this trajectory of decline it’s hardly surprising that journalists such as Andrew Probyn suggest that the Aston outcome “points to an existential crisis for Peter Dutton’s depleted and withered Liberal Party”. (That word “existential” has been over-used ever since some journo re-read Sartre a few years ago and thought it was a pretty cool word.) But in plain language, Probyn warns that the party in its present form is in terminal decline. It can quietly die, or turn towards “reinvention and renewal”.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s David Crowe summarizes the party’s problems:

The weakness in the Liberal Party is structural and profound: the party has lost power across mainland Australia, the membership is low and the branches are mesmerised by conservative culture wars. And Sky News sends out a beam of light every night to lure the branch members even further to the right – like a lighthouse on the wrong rock.

The challenge for the media – think beyond “the leader”

Following Dutton’s blustering and defensive appearance on Insiders, in which he essentially said that the Liberal party doesn’t need to change a thing, three experienced journalists – Raf Epstein, Niki Savva, Phillip Coorey – gave their interpretations of the by-election.

They believe that Dutton’s modus operandi – oppose everything, set traps for the government, and blame the government for everything that goes wrong – is not working with the electorate. That may be correct, but why are they so focused on “the leader”?

Dutton himself contributed to that focus when he described the election as an assessment of his performance. In the Insiders interview he accepted personal responsibility for the loss. That may be a gracious gesture to an unsuccessful candidate, but he is surely over-stating his own importance. In his post-mortem interview Jason Wood assured us that Dutton is really rather warm and cuddly once you get to know him, but that has little to do with the party’s problems. A moment’s reflection on our political history confirms that there is little connection between a politician’s personal behaviour and his or her party’s electoral support.

The Liberal Party is more than Dutton – much more. Many of its problems go back to its branches, its declining and unrepresentative membership, and the attempts by some of those members to pursue agendas that have little to do with any realistic concept of the national interest by any “left” or “right” criteria. At the parliamentary level many of its policy shortcomings seem to relate to its subservience to the mining industry and to the Murdoch media.

Having successfully scapegoated Morrison for its failures, is it going to do the same with Dutton? The media seem to be pushing it in that direction.

Don’t think that the political future will be like the past

Speers and the journalists he gathered around him for that post-mortem are some of Australia’s finest political journalists, but they seem to be too constrained by the inertia of past patterns.

They knew that something big had happened when a government won a by-election from the opposition, but they seemed to treat this as something of an outlier, ignoring the clear trends indicating that our political landscape, particularly on the right-of-centre, is going through a re-alignment.

Last Saturday’s election loss should be seen as something like the 1986 Chernobyl explosion – a spectacular event that brought to the world’s attention the decrepit state of the Soviet Union. The USSR had been decaying for years, and it would still be a few years before Gorbachev was to kick in the rotten door, but it took the Chernobyl disaster to draw the world’s attention to that decay.

The slow erosion in the two-party vote, the rise of “Teal” and other independents, the Coalition’s continuing losses in 21 of the last 22 state and federal elections, the Liberal Party’s accumulating losses in our big cities, and the loss of both main parties’ traditional voter base, have been going on for years, in plain sight but as unspectacular and incremental developments. The Aston by-election should be our Chernobyl moment, but we’re not seeing it that way. John Howard expressed the general feeling when he tried to reassure the party faithful that there will be some return to normal.

When the journalists on the Insiders panel went on to contemplate what might happen from here on, they offered their speculations, but they were unimaginative, as if the perpetual existence of a Labor Party and a National/Liberal coalition is written into our constitution. Mostly the discussion was about a possible leadership challenge some time in the future as the party muddles on – again the focus on “the leader”.

They didn’t raise other possibilities – the party falling apart; the party going through a root-and-branch re-constitution as it did under Menzies in 1944; the party splitting as Labor did in 1955; the Liberal and National Parties going their own ways; a new party coalescing around disillusioned party members, centre-right independents, and defeated candidates like Roshena Campbell.

It is telling that hardly anyone in the political establishment saw the Aston result coming. Had Dutton been well-informed he surely wouldn’t have called the by-election a verdict on the leaders, and Albanese would have been close at hand in Melbourne on Saturday night to appear on TV with a victorious Mary Doyle, but it was Dutton who was on hand to appear with Roshena Campbell. If Doyle had just scraped over the line these misjudgements would be understandable, but such a gross failure to read the electorate says something about pollsters, journalists and politicians. One journalist who went against the tide, however, was Paul Bongiorno, whose Saturday Paper contribution – Dutton sweating on Aston by-election result – did not rule out the possibility of a Labor win.

The whole response suggests that our journalists have so much invested in the established two-party arrangement that they cannot see its fragility.

1. Among these 17 seats are Dickson, Fadden and Forde, classified by the AEC as “Brisbane surrounds” rather than as “Brisbane urban”. ↩

2. There are about 17 million Australians on the electoral roll. Each year about 170 000 Australians die. That’s one percent of voters. Assume all are over 55, and that two-thirds of them are Coalition voters. That means each year the Coalition vote falls by two-thirds of one percent, or by two percent in three years between elections. OK it’s a rough calculation, but it starts to explain some of the Coalition’s long-term problems. ↩

Can the Liberal Party learn in defeat?

Federal

Within 12 hours of the party’s defeat in Aston Peter Dutton was on Insiders assuring viewers that he intended to learn nothing from the unexpected outcome.

His general line was the patronising assertion: “I know something that you and your viewers don’t know, but I won’t reveal my sources”. He knows that many women are deeply worried about LBGTQI issues and that it’s the main thing on their mind. He knows that the government’s safeguard mechanism will force Australia’s steel and cement industries to shift offshore. He knows that business people are publicly voicing support for the government’s policies not because they agree with them but because they fear retribution if they don’t support them.

That’s the tactic of shysters and conspiracy theorists: make a claim that’s unable to be verified or falsified. It’s the political equivalent of “sovereign citizens” asserting that 5G is ruining our health in some way that’s so mysterious that it cannot be disclosed.

Speers eventually asked “what does the Dutton-led Liberal Party stand for”, evoking the reply:

We stand for aspiration, we stand for entrepreneurship and small business. We stand for national security obviously, and we also stand for cleaning up a Labor mess when we get back into government.

No reflection. No acknowledgement that the government elected last May is cleaning up the mess his party left after nine years of failing to address the nation’s economic structure.

Instead of acknowledging the need for policies that match society’s needs, Dutton trotted out the same old Liberal Party line that a Coalition government will allow voters “to keep more of their own money”. That’s code for low tax and austerity in public services.

It’s also blatantly deceitful. Indeed, under the Coalition’s policies voters may pay $X less tax, but because of cutbacks in health, education and infrastructure they will have to pay more than $X in private health insurance, private school fees, university debt, road tolls, damage to their cars on potholed roads, and to deal with the consequences of climate change. It’s a blatant lie for anyone in the Coalition to claim that their policy of small-tax-small-government will allow people to keep more of their own money.

A 6-minute interview with Dan Tehan, member for Wannon in western Victoria, on the ABC 730 program revealed a great deal about the Liberal Party’s problems. His responses to Sarah Ferguson’s questions brimmed with self-assurance: the Labor government is responsible for cost-of-living problems, “our values have made us the best political force in Australian politics since the second world war”, “we have always governed knowing that a strong economy is what has really been one of the fundamental things that has defined us”. There was not the slightest hint that Australia’s present economic problems stem from the Coalition’s economic values, particularly its “small government” obsession. It was like hearing a member of Afghanistan’s Taliban government justify its gender policies.

The most revealing aspect of the interview came in response to a question about his support or otherwise for a Voice to Parliament. He had talked about how the party needs to get out and talk to voters, but when asked about that specific issue he said “I will listen to what my colleagues have to say”: his and the party’s “position” will be determined by discussions with the party’s inner core.

Tehan’s interview confirmed the saying that a party that listens only to itself cannot be elected.

New South Wales

Last week the New South Wales branch of the Liberal Party has been licking its wounds after losing the state election. The election campaign had been far less rancorous than last year’s federal election. But according to a long article in The Saturday Paper by Mike Seccombe, rancour has emerged in the post-election conflicts within the Liberal Party: He’s not Bambi: how the Liberals lost NSW.

After an election defeat the party dynamics become ugly as all the tensions that had been suppressed during the campaign come to the surface, but at least there is usually some attempt to reflect on what went wrong and on what went right.

That’s not so in New South Sales, because the right faction of the party is quite sure of what went wrong: Dominic Perrottet and his Treasurer Matt Keane had taken the party to the left.

Seccombe’s analysis and accounts of bitter confrontations and accusations give some insight into why Perrottet immediately stood down as party leader and why Keane did not stand for leadership, even though many independent observers credit Keane for limiting the extent of the government’s defeat. Seccombe reports on Keane’s reason for choosing “to spend some time with his family”:

He needs a little time, he tells The Saturday Paper, to “decompress” and recover “from all the beating I got from News Corp, the Minerals Council et cetera. That stuff that takes its toll.”

The reaction of the party’s stalwarts to the election loss is that it should move to the right. Seccombe goes on to observe that:

A coalition of forces – fossil fuel companies, gambling companies, small government ideologues, social and religious conservatives, and populist media that see commercial value in stirring division – were fighting for vested interests and against a changing society.

It was hard enough for reasonable, decent people like Perrottet and Keane to deal with these forces when they were in government. In opposition they wouldn’t have a chance to stand up against them.

As an aside, now that it’s clear that Labor will be governing in minority, it’s informative to take a look at the so-called “crossbench”. The ABC’s Heath Parkes-Hupton has a set of short political biographies on the people on whom Labor will be dependent for passing legislation: Who's sitting on the crossbench in NSW parliament, and what they'll be asking from Labor. There may yet be hope that the new government will be forced to enact strong gambling reform, which would be a benefit for all the country.

Polls – the Voice and war powers

The Voice

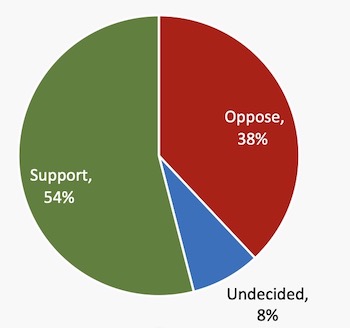

William Bowe reports on a Newspoll published on the morning before Dutton decided to make the referendum a gladiatorial campaign between Albanese and himself.

Support is at 54 percent, opposition at 34 percent.

Because for a referendum to succeed there has to be a “yes” vote in a majority of voters and a majority of states, attention should be paid to state support. Support is strongest in South Australia (60 percent), Victoria (56 percent) and New South Wales (55 percent), while in Queensland support is only 49 percent.

We can expect Dutton’s scare campaign to focus on Queensland and two other states judged to display soft support. Votes cast in the territories, the ACT and the Northern Territory are included in the overall count, but these jurisdictions don’t count as “states”..

Essential Report – we still love Albo, but we don’t trust him to declare war

The fortnightly Essential Report finds that 90 percent of us believe that “the prime minister should be required to get approval from parliament before making a decision to go to war”. Other questions cover the usual political topics, and there are some specific questions on cost-of living. The survey reveals few other surprises:

- Albanese is still enjoying high approval, but his net approval has been falling over his ten months in office.

- Many people, particularly those with a mortgage, are struggling to meet housing expenses, and that people older than 55 find it easier to meet expenses than younger people.

- Most people believe that the federal government can have a significant impact on the cost of living (but that belief doesn’t seem to have influenced Aston voters).

- People would like the government to do many things to cut the cost of living – cap electricity prices, increase the minimum wage, cut income taxes … It’s not a particularly informative question, however, because it fails to link those preferences to attitudes to taxes to pay for them: any reasonable person would welcome all these measures if they were free. Surprisingly, Green voters are more in favour of cutting fuel excise than Coalition, Labor or “Other” voters.

- About half of respondents feel financially secure while the other half don’t, but over the past year there has been a growth in the proportion of people who feel insecure. Women feel less financially secure than men, but there is no discernible difference by age.

- More of us believe that Australia is doing enough to address climate change. There are strong partisan differences on this question – for example 31 percent of Coalition voters believe we are doing too much. Younger people are more likely than older people to believe we are doing too little.

- On questions about actions to address climate change, Labor and Green voters are much more inclined than Coalition voters to support specific initiatives, such as a national authority to manage the transition to renewable energy.

True crime stories

We all know that crime rates are increasing, don’t we? That’s why we reasonably urge our governments to be tough on crime, and it’s why political parties hardly ever fail with a “law’n’order” platform.

The trouble with this perception is that it’s wrong. Rates of violent crime are falling, and have been for many years.

Specific crime rates are hard to measure, because of changes in reporting, but homicides don’t go unnoticed or unreported. Over the last 30 years, since 1990, homicide rates have fallen from around 1.8 per 100 000 people to 0.8 per 100 000, shown in the graph below. (Note the Covid blip.)

This trend, and details by state, relation of victims to offenders, use of weapons, motivation of offenders, and a range of other cross-tabulated data is published in the Australian Institute of Criminology Homicide in Australia 2020-21, compiled by the Institute’s Samantha Bricknell.

One finding that is almost always revealed in such reports is that overwhelmingly the perpetrator and the victim are known to each other. There is only a small rate of homicide by strangers, at around 0.1. to 0.2 per 100 000.

Men are both the perpetrators and victims of homicide, but men are far more likely to be the offenders. The trends are slowly converging: in particular the rate of women being murdered by their intimate partners is falling quite steeply.

Also unsurprisingly, indigenous Australians are much more likely to be victims of homicide than other Australians.

The AIC report is straightforward and factual, without any interpretation. In The Conversation Terry Goldsworthy and Gaelle Brotto of Bond University provide a summary of the report and some context: Australia’s homicide rate is down over 50% from the 1990s, despite a small blip during Covid. They point out, for example, that the homicide rate in the USA is now ten times the rate in Australia.

They also point out that in spite of the objective data showing an ongoing fall in crime (assuming homicide is a robust indicator of all violent crime), our perceptions of crime and fear of public spaces remain high.

That’s why “law’n’order” campaigns work.