Economics

The Chalmers-Taylor debate

Two well-qualified people, one with a PhD in Political Science, the other with a Masters in Economic Philosophy from Oxford, as well as a string of undergraduate degrees between them, come together to discuss economic policy. One is from a party with a social-democratic tradition, the other is from a party with a more free-market tradition.

Give them 20 minutes to argue in a civilized manner and there should emerge contrasting ideas about minimum wages, preferences for fiscal or monetary policies, the role of government in health care and education, choices between progressive taxation and redistributive welfare, and specific ideas about Australia’s future – whether we can sustain a long-term high rate of immigration, whether we need to restructure the economy away from dependence on mineral commodities, how we should handle future pandemics, and how to decarbonise the economy.

What we got instead was a waste of airtime in the Chalmers-Taylor debate.

The first 7 minutes were about fiscal matters – the bookkeeping of economic management. They would still be arguing about debt and deficit if the compere, Sarah Ferguson, had not told them to move on to housing policy. That discussion went over already well-grazed ground. And then on to energy, where Taylor gave ridiculously low-cost estimates for constructing nuclear reactors, and said that Coalition’s nuclear power plan would result in a “44 percent reduction in energy prices”.

Out of all of Taylor’s silly statements, that claim about prices is the most blatantly untrue. The Coalition’s modelling predicts a 44 percent reduction (from AEMO’s forecast) in the nation’s electricity bill, not the price of electricity. That 44 percent reduction assumes that there will be only very slow growth in electricity demand. Furthermore the modelling is about electricity only, not energy – people would still be paying for gas in separate bills. And the modelling does not say prices will fall by 44 percent. One’s electricity bill is a function of price per kWh and the number of kWh used, and it is quite possible that a 44 percent lower bill is associated with an even higher price. Chalmers tried to intervene on this deception, but the compere blocked him from making that point.

Taylor tried to defend the Coalition’s once-off cash injections – the $1200 tax rebate, and the 12-month cut in excise – as necessary cost-of-living relief. It was a pathetic defence: why does the economy need two fiscal injections, one of which is targeted to a small number of people who own oversize vehicles, when the Reserve Bank is in the process of giving more widespread relief through lowering interest rates. In fact unnecessary fiscal injections could cause the Bank to pause its interest-rate reductions.

Taylor did a brave job trying to defend the Coalition’s idea of allowing mortgage interest to be claimed against income, and its reversal of promises not to give the economy a sugar hit with tax breaks. We should have some sympathy for him: it takes a certain amount of verbal dexterity to defend ill-considered proposals made on the fly. The LLB he picked up along the way has turned out to be a useful qualification.

Trump’s damage to the Australian economy

Treasury has produced its Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook. (Not to be confused with the Parliamentary Budget Office Election Costings, which we probably won’t see until 24 hours before the polls close and most people will have voted).

With the election coming straight after the budget we would not expect there to be any significant change. There has been the Trump tariff disruption, however. The PEFO acknowledges that this has added to global uncertainty and will have a particular effect on China, our major trading partner. Nevertheless the changes on economic and fiscal outlooks are so minor that they make no significant change to the post-budget outlooks, covered in the roundup of March 29.

It should be remembered that in the budget there is the assumption that iron ore prices will be $US 60 a tonne, allowing plenty of room for a fall in prices, which are still close to $US100. This means that come this time next year the treasurer will probably have less opportunity to pull fiscal surprises out of the hat.

Trashing the Greenback

Contrary to Trump’s rantings, the world has been very kind to America. The status of the US dollar as the world currency, and the world’s faith in American economic stability, has allowed the country to borrow at low interest rates from the rest of the world. This, in turn, has allowed the US to have an ongoing trade deficit (the deficit that’s upsetting Trump), and a large fiscal deficit. Varéy Giscard d’Estaing, French Finance Minister in the 1960s, called that situation America’s “exorbitant privilege”.

That fiscal deficit is now around 6.6 percent of GDP, and net government debt is about 100 percent of GDP. For a perspective on those figures Australia’s fiscal deficit is about 1.5 percent of GDP and our net government debt is about 20 percent of GDP. Imagine how the world’s financial markets would deal with Australia if we had America’s figures, if we were looking forward to adding another 2 percent of GDP to our fiscal deficit to finance tax cuts, and if we were governed by an ignorant narcissistic madman with eccentric economic theories. The consequences would be some combination of a dramatic devaluation of the $A, very high interest rates, runaway inflation, and a policy response of extreme austerity involving high unemployment and savage cuts to government services. (Fate gives countries some choice over which of these pestilences they will suffer.)

According to The Economist – A flight from the dollar could wreck America’s budget – that’s a possibility America now faces, or has just narrowly avoided. Trump’s tariff moves have demonstrated that his policymaking is “arbitrary and capricious”, and there is sense of unease that goes beyond economics:

Mr Trump’s willingness to defund universities that house his critics, to withdraw government business from law firms which work with his legal opponents and to deport migrants to a prison in El Salvador without a hearing appears to threaten the norms on which American society has been built.

The Economist has a fairly thick paywall, but Gareth Hutchens covers much of the same ground in his post Are Donald Trump's tariffs destroying America's “exorbitant privilege”?

Trump was able to laugh off the stock market crash. But he wasn’t able to laugh off the subsequent rapid rise in government bond yields. As domestic and foreign traders sold American shares they weren’t putting the proceeds into US government bonds. Suddenly it looked serious, because the world’s traders were losing faith in the US as a safe haven. That fear of a run on the dollar was probably the reason for Trump’s backdown on tariffs.

As Hutchens says, if the US loses that exorbitant privilege, it isn’t easy to restore it.

In past times, when the world has been in turmoil, the US has enjoyed comparative economic stability, even when the US itself has caused that turmoil, because people have seen the US economy and the $US as safe havens. There is now no guarantee, however, that such a fortuitous situation will prevail.

Hutchens draws on Barry Eichengreen’s 2011 book Exorbitant Privilege: The rise and fall of the dollar and the future of the international monetary system to suggest that if the US dollar does fall out of use, either precipitously or slowly, it won’t be replaced by another currency, such as the Euro or the Renminbi. Rather there will most probably emerge a multi-polar world with multiple reserve currencies.

The strength of the US dollar, and its global acceptability, has been a matter of prestige for Americans, even when that was not in the country’s economic interests. In 1944, at the Bretton Woods Conference, Keynes warned the US against allowing its dollar to become the world currency, because that exorbitant privilege carried too much moral hazard. The US ignored his advice.

Hutchens’ analysis is pretty well in line with the way most economists have looked on America’s “exorbitant privilege”. On Late Night Live, however, David Marr interviewed Yanis Varoufakis – once an economics lecturer at the University of Sydney and for a time the Greek Minister of Finance – who is known for his well-argued views that often go against the macroeconomic mainstream.

His description of the global finance system, and the recent moves in the US dollar and bond markets, align with the mainstream, but where he differs from others is his belief that Trump actually wants to see the US dollar substantially devalued, and he wants to see an end to foreigners propping up the bond market. After all, a low-valued currency is a form of protectionism, without the hassles of administering a tariff system. That’s still in line with mainstream thinking, but Varoufakis describes a way, involving crypto-currencies, in which the US dollar would no longer be the world currency, but the US would still be able to exert a strong role in financial markets. (That part is well beyond my pay grade.)

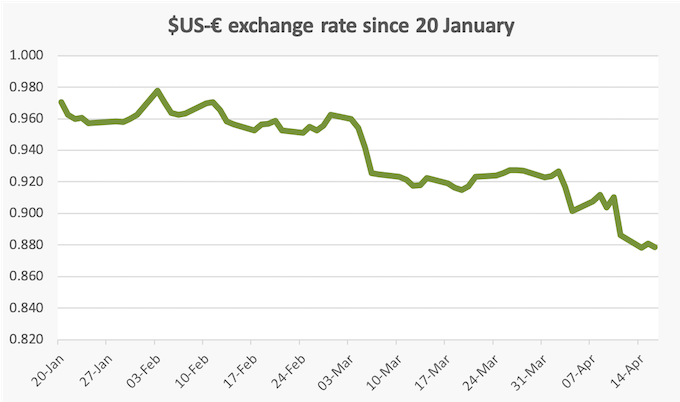

Australians who keep up with the news learn every day what is happening to the $A-$US exchange rate. That has been somewhat volatile, but it masks what has been happening to the $US against other currencies because at times in the last couple of weeks our dollar has been moving in sync with the US dollar. We get a better picture of the $US moves if we look at it in relationship to another major currency, the Euro. Since Trump’s inauguration, January 20, the US dollar has fallen by 9 percent against the Euro. Varoufakis seems to be on to something.

Varoufakis’s most recent book is Technofeudalism: what killed capitalism.

Where are house prices headed?

There is a broad view that house prices will rise for the foreseeable future. The logic is simple: Demand > Supply, and all the proposals announced by the established parties are tilted more to demand than supply.

But do we think house prices should keep on rising?

Peter Dutton made the provocative statement on Monday that he wants house prices to increase steadily to protect home owners. That statement should have provoked a strong response, but Dutton has been saying so many stupid things lately that the press hardly noticed it.

Most reasonable people would reject Dutton’s statement straight away: housing is a basic right, not to be treated in the same way as a share portfolio. We do not want to see the commodification of housing. Nor do we want to see housing become even more unaffordable.

But the idea of rising house prices is worthy of a little more consideration. If we compare houses built today with those built 25 or 50 years ago, there has been a definite improvement in quality, particularly in terms of convenience and size, such as two or more bathrooms becoming a norm. Sometimes as a result of regulation new houses have higher standards of insulation and fire safety. (Economists refer to these changes as “hedonic”, making for difficulty in constructing meaningful price indexes.)

For these reasons we would expect the prices of houses to rise in real terms. Also there have been improvements in safety standards on construction sites, which probably come through as higher prices.

But those are all about construction costs, rather than the price of land, which rises because of scarcity. It’s not a geographical scarcity – Australia is not Hong Kong – but it’s scarcity because of amenity, which relates back to a neglect of national spatial planning.

They actually depreciate in real value over time

And what is Dutton referring to – nominal or real house prices? Because economics isn’t his strong point it would be unreasonable to expect him to make the distinction. But there is a case for the nominal price of houses to at least keep up with inflation generally. In that way the real value of people’s outstanding mortgage debt slowly falls, making up for borrowers’ tendency to become over-committed when they first take a loan. Older Australians will remember that in the 1980s nominal housing interest rates were around 15 percent, but inflation was around 10 percent, which meant that the real interest rate was only about 5 percent and the value of outstanding loans was falling at 10 percent a year.

That’s not to advocate a return to 10 percent inflation. But it is a warning about what happens when inflation becomes too low, which is why the government and the Reserve Bank agree that CPI inflation should be within a band with upper and lower limits, that lower limit being 2 percent.

But it’s doubtful if that’s what Dutton was talking about. His attempt to make a scare campaign out of Green calls for reforms to capital gains tax and negative gearing suggests he is talking to his base – the people who hold multiple “investment” properties. And he is probably counting on what economists call the “wealth effect” of rising house prices, which applies even to owners of only one property, although it is only the illusion of inflation. The Coalition’s embrace of the wealth effect was most clearly manifest in John Howard’s statement that he had never met anyone who complained about their house going up in value.

Unless we are about to sell our house its price should be of no concern and even then, if we’re moving into another house, its price will probably have moved in a similar direction. Only if there are big regional differences in house price changes should sellers and buyers be concerned about house prices.

Measuring financial stress

The e61 Institute has published a short research note on measuring financial stress.

Over the last couple of years normal talk about making ends meet has morphed into a story about a “cost of living crisis”, preparing the ground for the Coalition to talk about “Labor’s cost of living crisis”. So prompted, it has been easy for people to respond to attitudinal surveys confirming the idea that almost everyone is really doing it tough.

The e61 researchers have gotten around this limit of self-reporting by looking at payment failures as indicators of financial stress. These are failures to pay rents on time, disallowed direct debits, and so on. Their research has focussed on direct debit failures.

Such incidents were at their lowest during the Covid pandemic, when there were specific income-support measures in place. They shot up in late 2022 as the post-Covid inflation began, and have stayed at that level since then.

In their search for possible drivers of payment failures they have looked at the different experiences of renters and mortgage holders, based on the supposition that interest rates would affect the former less sharply than the latter, but they find no conclusive evidence supporting that proposition. Both inflation and interest rates seem to have been contributors to financial stress.

They found that 21 percent of respondents had experienced a direct debit failure during the last month. Some of these failures may have resulted from disorganization, but the researchers noted that those who missed direct debits also manifested other indicators of financial stress, such as having less than $100 in the bank.

There is nothing in this study to state categorically that X percent of the population is suffering financial stress. Its main finding is strong evidence that financial stress rose and stayed elevated during a period of inflation and high interest rates.