Economics

Apart from a misleading statement on inflation, no surprise from the Reserve Bank

The RBA statement accompanying its decision to lower the cash rate from 4.35 percent to 4.10 percent almost reads like an insincere forced concession. It is still defending its tough line:

The central forecast for underlying inflation, which is based on the cash rate path implied by financial markets, has been revised up a little over 2026. So, while today’s policy decision recognises the welcome progress on inflation, the Board remains cautious on prospects for further policy easing.

It seems to be upset “that that labour market conditions remain tight and, in fact, tightened a little further in late 2024”. They don’t want workers to feel too secure in their jobs. (Labor force data that came out two days later showed that there has been very little movement in the labour market.)

It has the misleading statement that “in the December quarter underlying inflation was 3.2 per cent, which suggests inflationary pressures are easing a little more quickly than expected”. That is wrong – in fact, because it is written by some of the most well-educated economists in Australia, it is reasonable to suggest it is deliberately misleading. In the December quarter, the seasonally-adjusted trimmed mean CPI rose by 0.51 percent, which, if annualized, is 2.047 percent – almost at the bottom of the RBA’s target range.[1]

That 3.2 percent is the rise in the CPI over 2024, not “in the December quarter”. The Reserve Bank’s insistence on justifying its decisions with a 12-month lagging indicator, when a more recent indicator passed on the same data set is available, may help explain why it has been too slow to raise rates when it should have and too slow to lower rates when it should have.

The full explanation of the Bank’s decision is in its Statement on Monetary Policy, where it notes, in something of an understatement, that “the election of the new US administration has the potential to lead to significant changes in policy settings.”

That’s about as far as it will go into politics. It does not mention the economic risk of a Coalition government being elected in Australia. But it does tacitly endorse the current government’s fiscal policy where it states “An upward revision to the outlook for public spending growth and a small lift to net exports from the depreciation of the Australian dollar are expected to be broadly offset by a softer outlook for growth in consumption”. That is essentially an endorsement of the government’s fiscal policy.

In relation to public spending it has a special section on the way growth in the health care sector has contributed to competition for labour, but it does not does not engage in the Coalition’s silly assertion that because most of this growth was in the public sector it wasn’t real.

Comments

John Hawkins, of the University of Canberra, has a Conversation post explaining the Bank’s decision. It includes a chart showing that our interest rates, since 2021, have generally been lower than rates in UK, US and New Zealand.

The ABC’s Ian Verrender explains why the RBA poured cold water on future interest-rate expectations. He points out, however, that it is rare for the RBA to make just one decision to raise or lower rates. There is usually a run of adjustments, which is consistent with the Bank’s established pattern of holding on too long before moving and then having to make a series of moves. (That’s possibly a result of their use of a lagging indicator as mentioned above).

Steven Hamilton, commenting on Radio National, explains how the tone of the statement on monetary policy, which was handed to journalists under embargo before the decision was announced, led him to believe that the Bank was justifying leaving rates on hold. The decision, he believes, was far from unanimous. By Hamilton’s analysis the decision is more about yielding to the pressure of market expectations rather than being guided by its own analysis – analysis that puts a heavy weight on what it sees as an overheated labour market. (6 minutes).

In this context it is notable that this was the last meeting of the present RBA board. The next announcement, by a re-constituted board, will be on April 1. By that stage they will have two months of the ABS monthly CPI indicator, a less comprehensive survey than the regular quarterly CPI. The report for January will be released on Wednesday.

On the ABC’s The economy stupid, Peter Martin interviews The Financial Review’s Miriam Robin and the ABC’s Daniel Ziffer number of commentators on the Reserve Bank’s decision. The consensus seems to be that the rate cut will have little impact on household finances, and that the Bank is considerably more hawkish than operators in financial markets.

The Coalition’s response – deliberate misinformation

The least helpful comment was by Coalition economic spokesperson Angus Taylor on Radio National: Coalition says rate relief has taken too long. No one expected him to come out with a frank statement that the Albanese government has done a good job in bringing down the inflation it inherited from the Coalition without causing a recession. According to Taylor our so-called “cost-of-living crisis” is a result of profligate government spending. He assiduously avoids mentioning what spending the Coalition would cut, and he doesn’t acknowledge that the government has been fiscally conservative: the budget surpluses, in his view, result from revenue windfalls. (8 minutes if you can bear it)

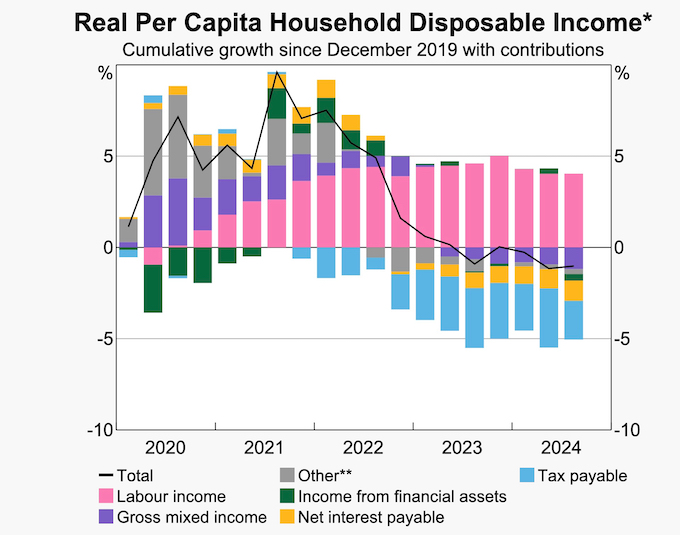

He draws on the finding that real per-capita disposable income has been falling since Labor was elected. He’s right, but he fails to mention that it started to fall on the Coalition’s watch, and he makes the ridiculous statement that this has been “the biggest collapse in our standard of living in history”. (Has he never heard of the 1890s and 1930s depressions? Is his knowledge of history as weak as his understanding of economics?)

Movements in per-capita disposable income are summarized neatly in a graph in the Reserve Bank’s statement, copied below.[2]

The high point in disposable income was during the pandemic: those grey bars in the graph are almost entirely government income-support payments.[2] As the graph shows, our household disposable income is now just a little below where it was when the pandemic broke out in 2020.

That’s consistent with the established trend in the economy. Since around 2014 there has been no growth in real incomes. That’s a reflection of our declining productivity, which in turn relates to a long period, mainly on the Coalition’s watch, in which there has been neglect of economic structural reform.

1. In the December quarter, the seasonally-adjusted trimmed-mean index number rose from 138.2761 to 138.9785.↩

2. The footnotes accompanying the graph are in Box B of the statement. ↩

Whyalla

It’s not a bail-out. It’s a nationalization – for now at least.

On ABC Radio National Breakfast on Thursday the South Australian Government’s rescue of the Whyalla steelworks received considerable coverage – from Premier Peter Malinauskas, whose government arranged for the business to be put into administration, from Edward Hughes, the State Member of Parliament for the Giles electorate which includes Whyalla, from the ABC’s Economic commentator Peter Martin, and from the ABC’s political commentator Melissa Clarke.

It’s not possible to link those contributions because the ABC’s website is a mess: if you wish to hear any of this description and commentary, go to the program’s whole recording (just on three hours), and stop at the following times (HH:MM:SS):

00:08:41 Melissa Clarke’s general coverage;

00:49:54 Peter Martin’s description of the rescue;

01:17:06 Edward Hughes’ account of how the rescue has been enthusiastically received in Whyalla;

01:29:25 Premier Malinauskas who explains the reason for the rescue;

01:42:00 Peter Martin with comments on industry policy and precedents.

Geoffrey Brooks, of Swinburne University of Technology, has a Conversation contribution: With Whyalla steelworks forced into administration, Australia has crucial decisions to make on the future of its steel industry, which goes through the history of Whyalla’s steelworks.

At this stage we don’t know what demands the rescue will put on public finances. The figure of $2.4 billion of joint Commonwealth and state funding has been announced, but some may be loans, some may be forgiveness of debt, some may be support the business would be receiving anyway through industry support programs, particularly the Future Made in Australia program. The Prime Minister’s website lists the support announced for Whyalla: Albanese and Malinauskas Labor Governments saving Whyalla Steelworks and local jobs with $2.4 billion package.

The point Malinauskas and others stress is that it is supporting the enterprise, not its owners. As Peter Martin says, it’s not being supported because it’s too big to fail: that was the gun the banks held to governments during the GFC. Rather, it’s being supported because it’s too important to the national economy to be left in the hands of the owners who have let it run down.

It is important because it is Australia’s only producer of structural steel and rails. The other major steel producer, Bluescope at Port Kembla, produces flat steel products. Australia needs both.

Most of our needs, other than rails, could be met from imports, according to David Uren writing in The Strategist – The strategic importance of the Whyalla steelworks – but he points out that there are also defence capability issues, because the high quality of Whyalla’s steel is suited to specific defence industry needs. In fact the Whyalla steelworks was established in 1941 for wartime strategic reasons.

The other justification for support is that, provided it is well managed, it has everything going for it as a low-cost steel producer. It is located near a source of very high-quality magnetite, it has a port, and a workforce experienced in steelmaking – an asset in human capital that is not easily replaced. It should be an attractive asset for a corporate buyer – Bluescope or a foreign buyer – once its finances are in order.

And it has access to low-cost clean energy: Spencer Gulf has large wind farms, it is climatically suitable for a large expansion in wind energy, and the inland is ideally suited for solar. Most of the renewable energy in the region so far is directed to electricity generation, but it can also be applied to generating hydrogen to heat the blast furnaces, and, in time, to replace coking coal and gas in reducing iron ore, which means Whyalla will become a producer of 100 percent green steel.

There is a great deal of confusion and misunderstanding about hydrogen, as some will have observed on Thursday night when the ABC’s Sarah Ferguson interviewed Industry Minister Ed Husic on the 730 Program. There is a medium to long-term vision which involves hydrogen (or ammonia – NH3) replacing compressed natural gas, to be shipped to distant ports and used to generate electricity. That industry is a long way from commercial feasibility, because so far it’s proven to be expensive to compress and transport hydrogen. Some companies in Australia have cancelled or deferred their plans for investing in hydrogen. The anti-renewables mob claim that these cancelations and referrals are evidence of Labor’s failed green agenda.

But the hydrogen to be generated for Whyalla’s steelworks will be locally produced, transported over a short distance, and used directly rather than as a fuel to generate electricity. Sanjeev Gupta’s plan for a large-scale hydrogen electrolyser supplying a wide market has been scrapped, but the state government still seems to be committed to a hydrogen plant specifically for the steelworks, once it gets the business running properly.

So far the Coalition, apart from making some snide remarks about hydrogen, seems to have supported the rescue. They would know that the Malinauskas government is popular in South Australia, and they know they will have a tough time contesting Adelaide electorates. How Australia has changed when a nationalization raises hardly a whimper in protest!

In fact they may have a battle on their hands in the large federal electorate of Grey, which includes Whyalla. Grey has traditionally been Liberal – they won it on a 60:40 TPP outcome in 2022. But in that election an independent without running a strong campaign picked up 11 percent of the vote. In the coming election an independent, Anita Kuss, will be standing with support from Climate 200.

The Grey electorate has extraordinary opportunities for renewable energy. To date it has been dominated by conservative rural voters, but there is generational change, and the more entrepreneurial people in the region are reacting against the Coalition’s opposition to renewable energy and their idiotic proposal to build a nuclear power plant at Port Augusta.

Wages are picking up, slowly

On Wednesday the ABS released the Wage Price Index for the December 2024 quarter, and on Thursday it released half-yearly Average Weekly Earnings data up to November 2024.

The wage price index shows a nominal rise in wages between 0.6 and 0.8 percent (depending on which specific series is used), which is just above the 0.5 percent in the CPI for the December quarter. Enough, perhaps, for a cup of coffee each week, but not enough for a beer.

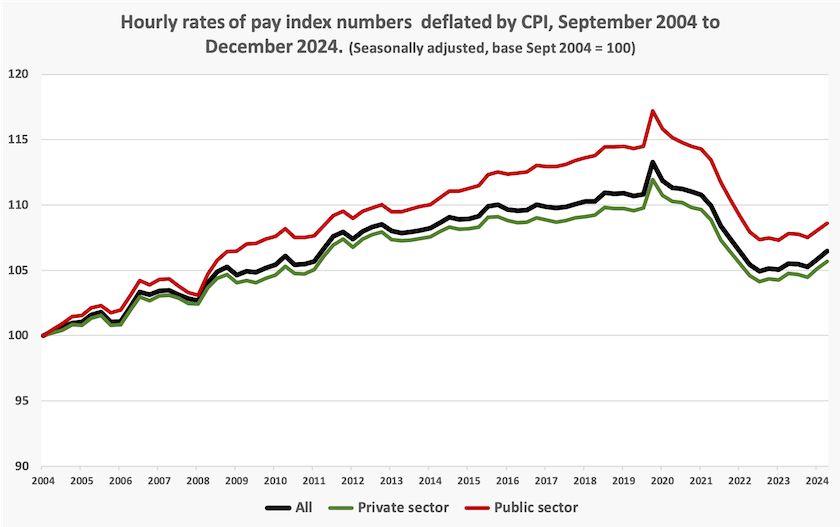

But at least, for the last six months, wages as indicated by the index have been rising, as shown in the graph below. Wages are now about 4 percent below their pre-pandemic levels. Public sector wages, however, have much further to go before they catch up.

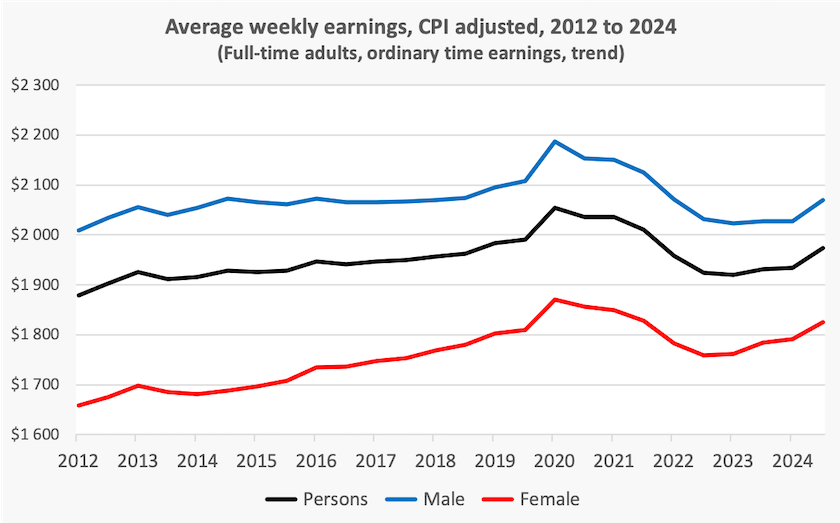

The story on average weekly earnings is similar. It shows for men and women a real rise in earnings of about two percent over the six months to November. Real wages for full time adults are now back to where they were in November 2018.

The wage price index and average weekly earnings can show different movements. Apart from the public-private sector division, the wage price index it is simply an indicator of the cost of employing labor across all industries. The average weekly earnings series is of adult employees only, disaggregated by gender, and it separates full-time from other forms of employment. The wage price index moves differently from average weekly earnings if there are changes in the composition of the workforce.

The economy through voters’ eyes

The latest Essential poll has two questions about how people view and assess the government’s economic management. The first is about people’s awareness of Labor’s achievements and the second is about how people rank the importance of Labor’s achievements.

On awareness, energy bill relief tops the list, followed by student debt relief, renewable energy targets, pay increases for aged care workers, and tax cuts, all of which score more than 50 percent awareness. There are only minor differences depending on people’s voting intentions. But there are gender differences: men are more aware of these initiatives than women. And there are age differences: older Australians are more aware of these achievements than younger Australians. Is this possibly a reflection on the way older people still get their news through traditional media?

On importance pretty well all score highly. Increasing renewable energy targets gets the lowest score, but that’s at a 70 percent score for “very” or “somewhat” important. Differences according to voting intention are strong: Coalition supporters attach far less importance to these achievements than Labor and Green voters do. They are particularly dismissive of renewable targets. Notably, in contrast with responses on awareness, women attach greater importance to the government’s achievements than men do.

Fiscal hawks, who tend to judge governments on the basis of the budget surplus or deficit, would be disappointed to see that of the eight achievements listed, “consecutive budget surpluses” gets the lowest score on awareness and a comparatively low score on importance.

Notably there is no mention in the polling about workplace reforms relating to the Fair Work Act and other employment laws. Perhaps Essential in its pre-survey sampling found that awareness of these changes was too low to survey.

That survey is about our current government. A reader has sent a link to a post by Matthew Davis on 1016 achievements of the Coalition government in its 8 years of office. It’s a truly impressive list. This is what we can expect from a Dutton government’s MAMA (Make Australia Mediocre Again) strategy.

How Australia is travelling – the Coalition’s MAMA vision

How do we perceive Australia to be travelling?

Essential has a time series, going back to early 2022, of responses to the question “In general, would you say that Australia is heading in the right direction or is it off on the wrong track?” For the last two years we have been much more inclined to say we are on the wrong track: about 50 percent say we are on the wrong track while only 30 percent say we are on the right track. Older people are particularly inclined to say we are on the wrong track, and women are more inclined to say we are on the wrong track than men.

Notably, before Labor was elected, older Australians were more inclined to say we were on the right track.

But what is that elusive “right track”? (Why don’t pollsters ask people to say what they think a right track would be?) The Coalition’s slogan is about getting Australia back on track, but what is that track? They don’t tell us much.

The best we can guess is that it’s about putting the Coalition back into office, so that we can carry on as we did under the Howard, Abbott and Morrison governments, perhaps best summarized as MAMA, or Make Australia Mediocre Again.

Australia Community Futures Planning, in their State of Australia 2025 Report, which pulls together 368 indicators of health, wellbeing and security, provides some vision about what that right track would be, and finds we are falling down in most dimensions.

In relation to areas where government policy can have an influence it notes the continuing growth of poverty and inequality, slow progress on climate change, a degraded public sector, serious problems with mental health, a failure to return to a universal health care system, underfunding of government schools and weakening commitment to multiculturalism, particularly in the Coalition’s ranks.

These seem to be areas where the Albanese government has not lived up to the expectations of those who voted for it in 2022. But by any reasonable assessment the Coalition’s MAMA vision would set us back even further.

Understanding productivity

The idea of productivity is simple. Productivity rises when we get more output from the same input, or the same output from a smaller input. It’s expressed as a simple difference equation: If (∆ Output ÷ ∆ Input) > 1, productivity has increased. QED.

Martyn Goddard, in his post Stop worrying about productivity. We’re doing okay takes us, step-by-step, through the meaning of productivity. He starts with the most commonly-used indicator, labour productivity, before explaining the ideas of capital and multi-factor productivity.

That’s the conceptually simple part. Then he gets on to the ways we measure productivity in different sectors. It’s easy to say that if we use a machine to substitute for grunt effort without sacrificing quality, labour productivity has improved. That’s what’s happened in manufacturing over the last two hundred years.

But it gets a bit more tricky when it comes to services, because changes in work practices and the use of informational technology, have changed the nature of services. Most estimates of productivity, including those used in national accounts, are derived from transactions in markets, where the output of a transaction is measured by the price we pay for the good or service. But perversely, if we pay more for a service because there has been price gouging, productivity apparently rises.

It gets even more tricky when we consider services provided in the public sector, because there is generally no price in the transaction – just our willingness to pay tax for public goods.

Finally Goddard gets into the specifics, looking at productivity in health and education. What is the “product” of a school, of a medical consultation?

Goddard bases his “we’re doing OK” claim on the basis of difficult-to-measure benefits of the quality of goods and services produced in the economy, and the services we just didn’t have in times past. For example cars have become cheaper over the years – that’s easily measured – but they have also become safer and easier to drive, much easier to navigate, they last longer, and they have become less polluting. How do we factor all those benefits into our productivity equation? Our rising life expectancy and lower rates of crime are significant benefits, but it’s almost impossible to pick them up in productivity measures.

If, after reading Goddard’s contribution, you feel you have a less firm grasp on the meaning of “productivity”, he will have gotten his message across.

Productivity in housing construction – a cottage industry

The Productivity Commission has issued a research paper: Housing construction productivity: Can we fix it?. While in most sectors of the economy labour productivity has been improving over the long term, in the construction sector, including in the dwelling construction sector, labour productivity has been falling.

Australia is not alone in this regard: this has been happening in many other countries.

The Commission puts this decline down to four factors: complex, slow approval processes, a lack of innovation, a lack of scale in building firms, and what it calls “workforce issues”, a category that includes restrictive and inflexible training for building trades.

It lists seven suggestions for policy reform, with a strong emphasis on simplifying regulation in ways that do not compromise on building quality.

The RBA’s construction problems

Writing in The Conversation, Michael Loosemore of the University of Technology, Sydney, summarises the Commission’s paper while casting a critical eye over some of its suggestions for simplifying regulation. In spite of the Commission’s cautious approach, he warns that they may result in poorer quality: Here’s why increasing productivity in housing construction is such a tricky problem to solve.

Perhaps policymakers need to cast a wider net when they look at the construction industries. Problems of poor scale economies, inadequate innovation, and poor workplace relations must surely relate to the lack of continuity in the industry, an industry where demand is influenced by monetary and fiscal policy settings. Construction – residential and non-residential – has always been the industry expected to expand and contract as directed by government stabilization policies. Firms in the industry therefore lack the continuity in demand that would allow them to invest in innovation, staff training and capital equipment. Steadier demand would allow them to bring services, presently contracted out, in house.

Maybe as the Reserve Bank observes the pitifully slow progress in renovating its Martin Place building it will realize that it has contributed to its own troubles.

Bus fare evasion

Milad Haghani and Neema Nassir of the University of Melbourne have a Conversation contribution about evasion of public transport fares.

In August last year the Queensland government introduced 50 cent public transport fares as a trial. That provided economists with a ready-made experiment which would allow them to estimate the price elasticity of demand for public transport – an important consideration for transport planning. When it lowered fares the government probably didn’t have research economists in mind: it was more like an election pitch. But it was so successful that the incoming LNP government has made it permanent.

Haghani and Nassir have looked at the Queensland data in relation to fare evasion. Economists would expect lower fares to result in less evasion and they do indeed find evasion in Brisbane has fallen significantly, but there are many variables to consider before they can conclude that this is purely a rational economic reaction to a price fall. Changes in the way people assess the risk of detection play a part in evaders’ behaviour, for example.

The other factor they note is the extent to which people trust the transit operators to be attending to their interests. Behavioural economists point out that consumers are interested in the price and the physical quality of a service – the basic Economics 1 model – but they are also concerned about the fairness of transactions. This has lessons for those who design welfare payments systems (Robodebt comes easily to mind), disability services and other public services. If we believe we are being screwed or mistrusted by a private business or a government service-provider, we will respond with equal mistrust, and will seek small ways to get our own back – probably in the ballot box if it’s a government entity.