Politics

The two-party dirty deal – a first step to restoring the duopoly

Independent members of Parliament and non-partisan observers have pointed out that the Labor-Coalition deal to “reform” election donation laws is grossly unfair. Even more seriously these “reforms” seek to shore up the old two-party system, with its tendency towards polarization. As we are seeing in the USA, a polarized democracy can give way to an authoritarian populist regime, paving the way for fascism.

In last week’s roundup there were links to immediate reactions from independents Zali Steggal and Helen Haines, who pointed out how candidate spending caps could be supplemented by much larger spending by political parties, and a link to Anne Twomey’s comment that the legislation is so unfair that, if challenged, it could be knocked back by the High Court.

Michael West has granted the deal the status of scam of the week. One aspect to which he draws attention is the agreement around the donation disclosure cap, which is presently $16 900. Labor went to the 2022 election promising to drop the cap to $1 000. But under Dutton’s insistence, that cap is now $5 000.

Kim Wingerei, also writing on Michael West Media, reminds us that the deal includes a disclosure carve-out for donations to “nominated entities”, such as the Liberal Party’s Cormack Foundation and “Labor Holdings”: The American way. Electoral reform bill to entrench major parties’ power. Wingerei sees this so-called “reform” as heading the American way – a political system characterized by low voter turnout, difficult voter registration, voter suppression, weak electoral laws, gerrymandering, and limitless donations.

It’s apt comment. Practices that set us apart from America – compulsory voting, a national electoral commission, and preferential voting – are legislated rather than enshrined in the Constitution. They are not safe.

Of these, preferential voting is probably the strongest protection against having a fully polarized two-party system. Historically preferential voting favoured conservative parties in Australia, when the United Australia Party and the Country Party were separate, and later it favoured the Coalition when the Democratic Labour Party split the Labor vote. More recently, with the rise (and demise) of the Democrats, and the rise of the Greens, preferential voting has favoured Labor. But it is possible to imagine a development where the Labor and Coalition vote settles around equal levels for each party, and they combine to abolish preferential voting.

We may be inclined to believe that the two-party system is a natural order. But in fact, as Frank Bongiorno shows in his Conversation contribution Splits, fusions and evolutions: how Australia’s political parties took hold, since and even before Federation, parties have risen and fallen. There have been changing alliances between parties and slow shifts in voter loyalties.

Where is this all going? Most observers believe Australia is heading towards a multi-party system, provided Labor and the Coalition don’t manage to stop it.

In his contribution on The Future of Everything site, The changing polarity of Australian politics, Tim Dunlop draws on Bongiorno’s essay and other sources to present a different framing of Australian politics. He suggests that for a long time there was a simple split – Labor vs non-Labor, which has flipped to a Coalition vs non-Coalition division.

He suggests that as Labor’s primary vote has fallen away, a new collection of left interests is slowly being assembled:

This opens a demand on the progressive left for a representation that Labor no longer seems willing to provide, especially around climate action, tax and housing reform. And then, as the LNP goes further right, pursuing the anti-progressive conservatism they are sure exists in the outer suburbs and in rural and regional Australia, a space has opened up for a gentler, more socially progressive formation amongst the professionals of the inner cities, a space that community independents arrived just in time to fill. They supplemented the role that was already being played by the Greens, but in electorates neither the Greens nor Labor were ever likely to win.

His premise is that there will always be some binary split, but is it really so simple?

That scary headline about Dutton becoming PM

The ABC’s coverage of YouGov’s poll, with the headline Peter Dutton most likely to be next prime minister, according to YouGov poll, looks scary for anyone concerned with the future of Australia’s economy and the risk that Dutton’s Trumpist, divisive political style might be vindicated.

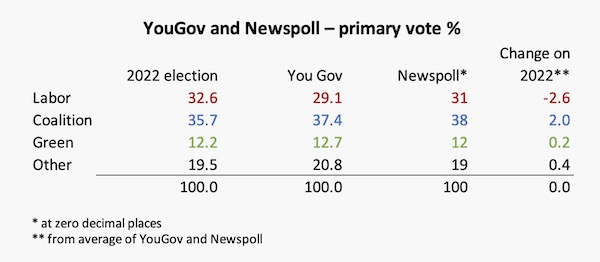

It’s a well-conducted poll. Its sample size – 40 689 – reduces the sampling error to a very low level. That means it’s more credible than recent polls (Morgan, Freshwater and Redbridge) that have estimated he Coalition primary vote at 40 percent or higher. It’s also close to the latest estimates published by Newspoll, which has a good track record for accuracy. These comparisons are shown in the table below.

That table shows that Labor’s support since the 2022 election has slipped, while the Coalition’s has risen, but not to the same extent. These are not the numbers associated with landslide shifts.

But the model built on the YouGov poll shows a very large shift to the Coalition in terms of seats it could win off Labor. At first sight this makes little sense. When one looks at national figures, it’s clear that a two to three percent swing isn’t going to deliver many seats to the Coalition: a three percent swing would deliver only 7 seats, according to the Tally Room’s pendulum.

The model is more sophisticated than simply applying national figures, however. It uses an established statistical technique of estimating the voting inclinations among different demographic groups (those with and without university qualifications, people in different age brackets and so on). For each of our 151 electorates the demographic characteristics of those electorates are used to estimate how those particular electorates will swing. In the article on the YouGov poll, linked at the beginning of this section, Casey Briggs explains the technique in more detail.

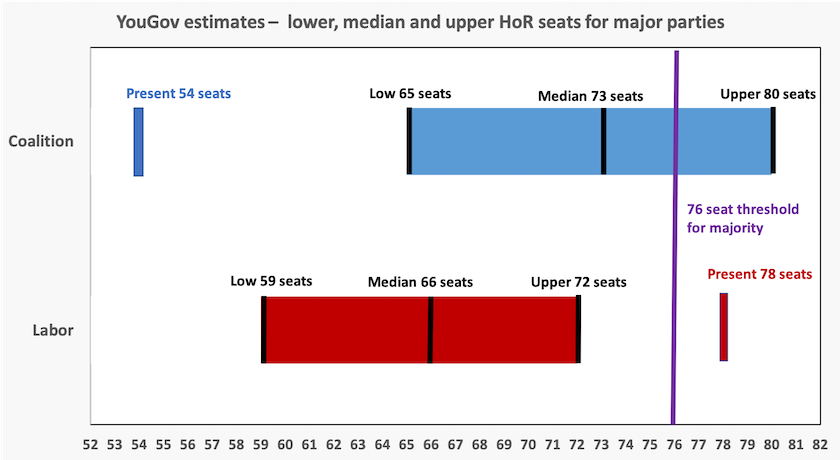

The statistically best estimate, based on adding all the electorate outcomes, gives Labor 66 seats and the Coalition 73 seats. There is a small chance the Coalition would win up to 80 seats – enough for a majority government, but there is no way, according to this model, that Labor would win majority government. This is all summarized in the chart below,

What stands out in the chart is the large number of seats – 19 – that the Coalition would have to win to meet this median. In simple terms that’s because while Labor holds only 7 seats on a three percent margin, it holds another 12 seats on a three-to-six percent margin. The model predicts that there could be such high swings in the outer suburbs, which brings the total up to 19.

More amazingly, the Coalition’s gain of 19 seats would be achieved without winning a single seat back off independents.

Assuming the model is mathematically correct, it’s an extraordinary confirmation of Dutton’s strategy of abandoning the Coalition’s once “heartland” constituents, avoiding any reference to economic policies, and relying on people’s gut feelings, mainly the idea that Australia needs to be “back on track”. That message has traction, even though the Coalition’s track record in office is of economic neglect – a failure to address the country’s mounting structural weaknesses, particularly in our tax system. But the Coalition does not have to explain itself, because everybody knows that they are the better economic managers.

Will Dutton’s “everybody knows” strategy work through to the election?

There are reasons to be cautious about interpreting what this survey can tell us about the outcome of the coming election. That’s not because of its methodology: it’s more thorough than the regular opinion polls, and its mathematics seem to be as rigorous as possible.

But outer-suburban Australia is more heterogenous than can be detected in a set of demographic characteristics. There are local factors affecting elections. For example the YouGov model classifies the Sturt electorate, covering Adelaide’s established eastern suburbs, as “safe Coalition”. Sturt, however, is about as “teal” as any electorate can be, and just in the last few days independent candidate Verity Cooper, backed by Climate 200, has emerged as an independent candidate. It will be a very hard seat for the Coalition to hold: in 2022 they won against Labor on a 0.5 percent margin.

Also in Adelaide YouGov is classifying Boothby, a relatively inner-city seat won by Labor in 2022, as “Lean Coalition”. But the Liberal Party in South Australia has been faring poorly for the Coalition. Similarly YouGov sees the Liberals winning Lyons off Labor, even though the Liberal Party in Tasmania is in a mess, and Lyons, covering the middle of Tasmania, has an established record of fickleness.

Then there is the possibility that the campaign will turn to policy issues. If the government or the media can force Dutton to explain what “back on track” means, he will have to explain what a Coalition government would do about power prices, to cost its nuclear power scheme, to explain what government services it would cut (health or education?), to lay out a plan to boost housing supply, to show how it would cope with our infrastructure backlogs, to explain how it would undo the government’s workplace reforms without allowing wages to fall, and to show how it would deal with skills shortages. That slender poll lead can easily slip away.

In sum the YouGov poll is just what it claims to be – a mathematically rigorous simulation of what the outcome would have been had an election been held sometime between January 22 and February 12 – the sampling period, before many independent candidates had started to make their presence felt. Fortunately there was not an election in that period. As Bob McMullan, writing in Pearls and Irritations reminds us “One thing that can be said with certainty is that the best polling in the world cannot make definitive predictions three months out”.

What will our next Parliament look like?

By now it’s reasonably certain that neither Labor nor the Coalition will have a majority in the House of Representatives. Also, as the YouGov poll (referred to above) shows, it’s likely that all independents will be returned and perhaps a few new ones will appear. The YouGov poll was conducted before the independents started to ramp up their campaigns, and before some had even started their campaigns. (Climate 200 has announced that they are supporting 35 candidates in the coming election.) And as Casey Briggs points out, the technique used by YouGov probably understates support for Greens and independents.

To illustrate the point that the election outcome is highly unpredictable, the Dickson electorate in Queensland was won by the LNP on a margin of 1.7 percent. The YouGov model classifies it now as “Safe Coalition” by a 54:46 percent TPP margin. But since the YouGov survey was conducted an independent candidate Ellie Smith, claiming to have backing from Climate 200, calling herself “maroon” rather than “teal”, has emerged, standing on mainly local issues.

That’s Dutton’s electorate.

Dutton losing his seat is perhaps at the extreme end of speculation, but it illustrates the difficulty of making too many seat-by seat predictions about the coming election. Just in the last few weeks there has been a surge of activity by well-resourced and well-organized independents. It’s too early for their influence (or lack of it) to show up in the polls. In fact, for reasons to do with mathematical limits of sampling, we may not learn much more about how independents are travelling.

From these numbers, who would form government?

Dutton has asserted that if the Coalition were to win more seats than the Labor Party he would expect crossbenchers to assure his party confidence and supply. It’s a predictable pitch – any opposition party would make it – but there is no such rule or convention governing the formation of government.

Laura Tingle, in her regular political segment on Late Night Live, goes through the possible strategies independents would adopt in a Parliament where no party has the clear numbers to form government. There are too many outcomes to summarize, and independent MPs are too politically savvy to give advance notice of their intentions. Indeed, they might not have clear intentions at this stage, because they would be waiting to interpret what the election tells them about the people’s expectations.

Also we should remember that the independents are not a party: they have won their seats through strong local campaigns. Apart from electoral reform, where they all have a stake, their issues vary. The “teals” are strong on climate change, administrative integrity, and seem to be united on gambling reform, but there are independents with their own strong issues, for example Allegra Spender on tax reform. There is no reason to suggest they lean towards Labor or to the Coalition: they lean towards issues.

Laura Tingle suggests that there are some issues, particularly his opposition to renewable energy, on which Dutton has invested so much effort that he will not budge. But is Dutton the only person who might lead a Coalition minority government? If he were to lose his seat the Coalition would have an opportunity to clean the hard right out of its ranks, and to embark on an economically responsible policy path. That could see independents endorsing the Coalition in a minority government.

Another possibility is that the Coalition does reasonably well, and Dutton holds his seat, but the independents grant support to the Coalition only if it dumps Dutton and other members of the hard right. That has a precedent in the 1922 election, when the Country Party, holding a balance of power, refused to join a coalition with the Nationalist Party unless its leader Billy Hughes resigned. The Nationalist Party yielded.

If, as is likely, the Coalition is a long way short of forming government, Labor could reasonably claim that it will continue in government until and unless it loses the confidence of the House, or is denied supply (by either chamber). There may be no need for a formal agreement with independents, who could assert their interests through private members’ bills.

Also overlooked in the discussion is the outcome in the Senate. Three independent Senators (Tyrrell, ex Jaqui Lambie Network, Thorpe, ex Greens and Payman, ex Labor) continue in office. If the outcome for the 40 contested Senator positions is the same as in 2019, the Senate composition will be unchanged in terms of party representation. The numbers would still pan out slightly in favour of Labor rather than the Coalition.[1] In the interest of having a government able to pass legislation, that would favour Labor forming government in the House.

1. That outcome would be as follows. NSW, Vic, SA, WA: 3 Coalition, 2 Labor, 1 Green. Qld: 3 Coalition, 1 Labor, 1 Green, 1 PHON. Tas: 2 Coalition, 2 Labor, 1 Green, 1 JLN (Lambie): NT: 1 Coalition, 1 Labor. ACT 1 Labor, 1 independent (Pocock). ↩