Public ideas

Nicholas Gruen seeks to seize a Magna Carta moment

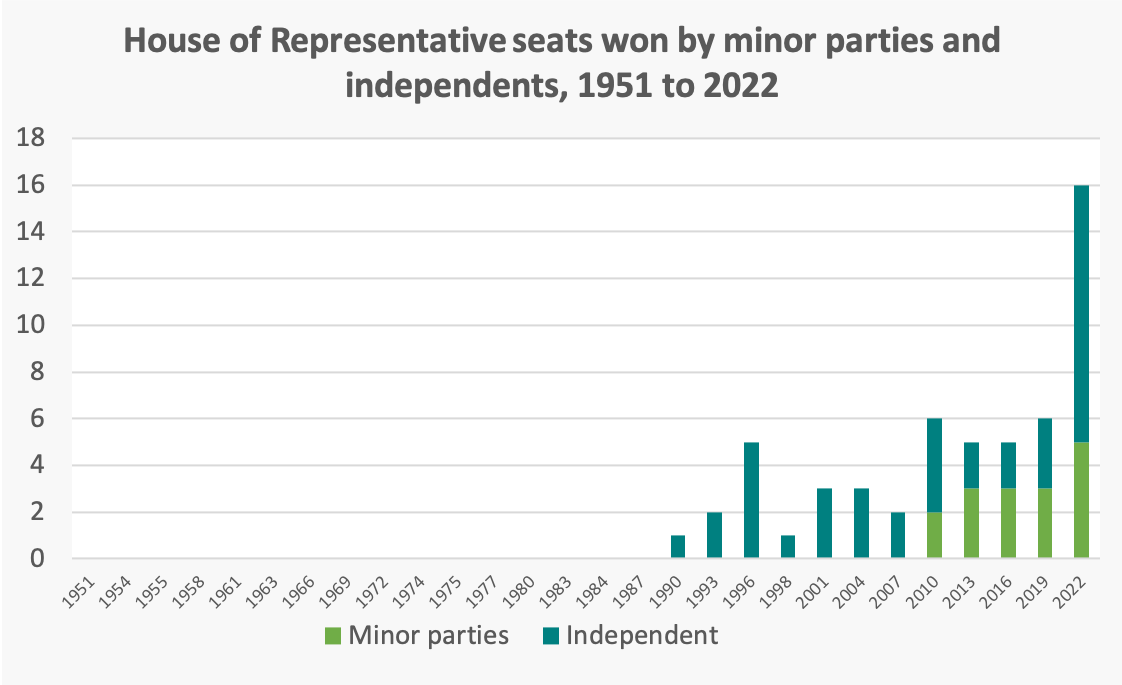

Over the last 75 years the combined Labor plus Coalition vote has fallen from 98 percent in 1951 to 68 percent in 2022.

Because of the way our voting system works – known as “ranked choice” or “preferential” voting – it has taken time for growing support for minor parties and independents to manifest itself in terms of seats won in the House of Representatives. The Greens made the initial inroads, but particularly noticeable in the last 15 years has been the success of independents.

Most political observers believe that this trend is established, and that it is unlikely that either of the old established parties will be able to form a majority government in the coming or subsequent elections. As Nicholas Gruen says in his Substack contribution – The logic of democracy (both kinds) – in this situation “the crossbench becomes kingmaker”.

In this context he hopes (and expects) to see greater use of citizen assemblies. Independent Allegra Spender is proposing one on tax reform, and others want to see assemblies on housing.

Citizen assemblies make a useful contribution to democratic processes, as Gruen acknowledges in a following article (same hyperlink) about the use of citizen assemblies to help governments deal with difficult and contentious issues, such as they did with abortion and same-sex marriage in Ireland. But as a means of reviving people’s trust in democracy they have their limits. They leave no institutional trace he says, and they are in a pre-democratic mode of the governed bringing their supplications to those who govern.

Gruen sees the problems of elective democracy as intrinsic to the way competitive elections operate: elections will always reward “performativity, manipulation and dissimulation”, rather than selection of lawmakers who serve the public interest.

That’s why he seeks to see “a standing citizen assembly effectively operating as a third house”, in parallel with established democratic institutions.

In a separate Substack contribution he presents a half-hour discussion with Gene Tunny of Adept Economics, who asks Gruen about details of how such a chamber would work – whether members would be paid, whether they would be able to seek expert briefing, and so on. It’s probably premature to get into too much detail, but Gruen stresses two important points. The first is that like legal juries, members would be chosen by lottery (an ancient principle). The second is that the citizen assembly should have only advisory powers.

Towards the end of the discussion Gruen outlines the political virtues of his proposal, including its inherent protection against corruption and against adoption of the gamesmanship strategies that plague professional politicians.

He sees a citizen assembly as an idea whose time has come, which is why he likens it to 1215, when the Magna Carta marked a major step in the development of democracy. In order to protect against democratic backsliding it is time for another Magna Carta moment. He acknowledges that it may appear radical to many people, but if we see it in action we will probably like it, which is why he uses as a metaphor a scene from When Harry met Sally. For those who are bamboozled by the talk about orgasms in restaurants, here is the relevant 3-minute clip.

Gruen refers to the Belgium model of standing citizen committees, described in a newDEMOCRACY paper The Brussels Deliberative Committee Model.

As Gruen points out, the constitutions and conventions guiding democratic processes were generally written at another time. A randomly-chosen citizen jury appointed today could have many more years of schooling than one appointed 100 years ago. Another factor worth considering is that it would probably give governments, protected by their Praetorian Guard of party insiders and professional public servants, early warning of seething discontent, so that the political class isn’t taken by surprise by events such as Britain’s vote for Brexit, or America’s election of Trump (twice).

Liberalism isn’t dying, but it could erode away

On the Persuasion website is an excerpt from Alexandre Lefebvre’s book Liberalism as a way of life.

The left is gloomy about the future of liberalism, as they observe the incapacity of liberal democracies to deal with difficult and urgent problems, and as they observe widening inequality and economic injustices. The right never had much faith in liberalism anyway.

But has it not always been so, asks Lefebvre?

From its inception liberalism has been under threat, but it is sustained by social norms of decency and cooperation, rather than by specific contracts or public policies. Those norms, or social mores, are deeply embedded in our lives. “They have a duration all of their own”, she writes. “Anchored as they are in one’s self-conception and routines, they can be stubborn and resilient”.

She warns, however, that we shouldn’t take her work as an optimistic assurance that liberalism will always thrive. It may not.

She refers to the enduring power of norms, but they are under severe assault. We need only to look at Trump’s behaviour, and at the people who justify it. Closer to home we can observe the behaviour of Dutton and his acolytes, who have re-defined politeness, tolerance and respect for others as “woke”: that’s an excuse to justify their own disgusting behaviour.

Lefebvre is a professor of politics and philosophy at the University of Sydney. Liberalism as a way of life is published by Princeton University Press.