Other politics

How we view Albanese and Dutton

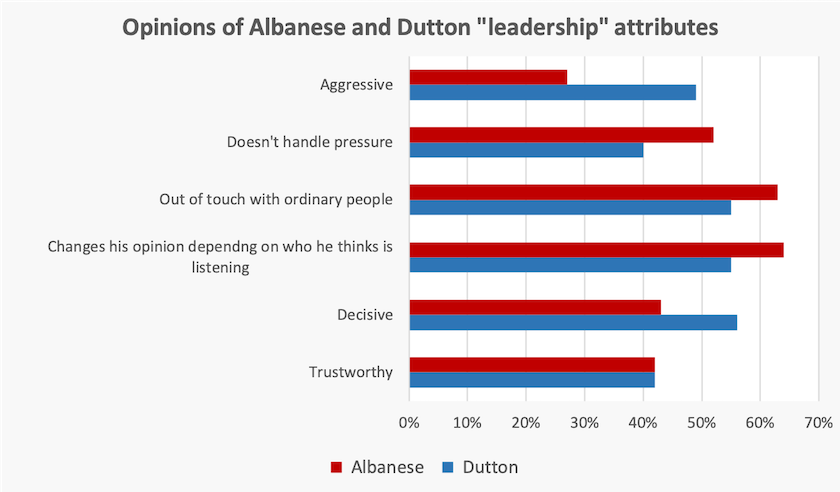

The latest Essential poll surveyed respondents on their assessment of Albanese’s and Dutton’s “leadership” attributes. (Separate hyperlinks).

The chart below combines these responses to see how they compare in terms of those perceived attributes.

Some may be surprised that they score equally on trustworthiness, but that seems to be because older voters assess Dutton as trustworthy while younger voters don’t. There is also a gender difference: women are less likely than men to assess Dutton as trustworthy.

Both score highly on the negative attribute “out of touch with ordinary people”. Notably on this attribute Albanese’s rating has worsened significantly since he’s been in office. There is also a significant age difference: older people seem to find Dutton more in touch.

The difference in handling pressure stands out and does not align with what people have observed in recent media appearances. Dutton rarely exposes himself to the stress of a media appearance. His most recent extended session was on Insiders last weekend, where he came across like an actor who had learned his lines but without any nuance or variation in expression, with the same cold inhumanity as early versions of text-to-speech programs. In contrast Albanese at his January Press Club Address, which was mainly a Q&A session with journalists, came across as fully on top of his brief.

The impression reported in the Essential poll is formed somewhere else – on social media perhaps, or simply the general message, spread by the Coalition and its supporters in the Murdoch media, that Albanese is “weak”. His inexplicable readiness to yield to pressure from the Coalition is probably contributing to that impression of weakness and inability to handle pressure.

This notion of weakness also comes across in voters’ impressions of decisiveness, where Dutton scores much higher than Albanese. Essential classifies decisiveness as a “positive” attribute, but is it really a positive attribute? Other terms that come to mind are “headstrong”, “authoritarian” and “pig headed”. If we want to observe a “decisive” head of government in action, we only have to look at Donald Trump.

Gender and age issues in voting intention – it’s not about cost of living, but what is it about?

Patricia Karvelas has a post on gender politics Is Peter Dutton deliberately blowing the bloke whistle ahead of the election?, in which she goes into worldwide and local gender issues that may show up in our coming election.

In democracies worldwide women, particularly young women, have been more on the “left” than men in their political attitudes. Women have overtaken men in education attainment, and have been more comfortable with workforce and social changes than men. By contrast men, particularly young men with limited education, feel left out and are easy prey for demagogues who thrive in the politics of resentment. It’s now reasonably clear that such young men have been strong supporters of Donald Trump.

On the other hand, Karvelas points out, Liberal Party strategists believe that the Coalition is closing the gender gap, which was particularly wide in the 2022 election. The so-called “cost-of-living crisis” is supposedly at play, because women are more exposed than men to price rises when they do the household’s weekly shopping, an assumption based on traditional gender divisions.

Also, there was something about Scott Morrison that women found particularly creepy. Dutton does not suffer that same disadvantage.

But as shown in the post above, women are less likely than men to find Dutton trustworthy. And in his eager emulation of Trump’s political style he has taken a swipe at the DEI movement (diversity, equity and inclusion), which over the years has undoubtedly helped women advance in the workforce.

You can read Dutton’s comments on DEI in a transcript of his recent speech at the Menzies Research Centre, or if you want a summary of his DEI points, without the rest of his re-interpretation of history and right-wing economic drivel, you can read Jacob Greber’s account: Mirroring Trump, Peter Dutton takes aim at diversity and inclusion workforce.

Karvelas reports that polling published in the Financial Review found there is still a sharp gender gap among young voters, with men far more disposed to Dutton than women are.

William Bowe’s Poll Bludger provides detail on this polling among people aged 18 to 34. One large gender gap is in support for the Greens – women 32 percent, men 20 percent. On primary vote men show a small preference for Labor (Labor 36 percent, Coalition 32 percent), while women show a strong preference for Labor (Labor 32 percent, Coalition 25 percent). It’s notable from these results that young women are close to giving up on the two-party duopoly.

When Kos Samaras converts these results to TPP estimates he finds a Labor lead of 59:41 among young men and a whopping 67:33 among young women. He also finds that as preferred prime minister Albanese leads Dutton by 55 to 37 percent among young men and by 58 to 27 percent among young women. But these are relative rankings: neither Albanese nor Dutton does well on approval.

Although polling disaggregated by gender and age tends to carry a high sampling error, the gaps revealed in these figures are so strong and consistent between different questions that they must surely be meaningful.

Surveys confirm that people in this age cohort are the most heavily impacted by rent prices, general inflation, and for those who have gotten a foothold in home ownership, by mortgage interest rates. If the story about a “cost-of-living crisis” driving people to vote for the Coalition were correct, these struggling young voters would be flocking to Dutton and the Coalition, but they have quite turned off the Coalition.

Because national polling shows lower support for Labor (31 percent), much lower support for the Greens (12 percent), and much higher support for the Coalition (39 percent), and essentially a TPP tie, for these figures about young people to reconcile with national figures, the Coalition must surely be doing very well among older voters, including those who are securely housed and have low or no mortgages, who have been least affected by inflation over the last three years.

Something else is drawing middle-aged and older voters to Dutton and the Coalition. Perhaps it’s his emphasis on culture and symbolism. In the same round of polling Essential ran questions on gender equality, beliefs on who has too much power (e.g. aboriginal Australians, LGBTIQA+ Australians ), and attitudes to diversity, equality and inclusion.

Our responses to these questions reveal us to be a fairly liberal and tolerant people, confirming the way we like to be seen. But when we look at the results by age we see harder attitudes among older people, particularly those aged 55 or more. These are people born before 1970, many of whom would have grown up in a highly gender-separated “white” Australia, where Aborigines knew their place and homosexuals dared not reveal themselves.

That’s where Dutton seems to be consolidating the Coalition’s base. It may help in the short-run, but in the longer run it’s probably leading the Coalition into oblivion.

We’re building more prisons when crime is falling

We have a housing shortage, as 38 000 Australians experiencing long-term homelessness can affirm. And we’re not building enough public housing.

But there is one area where public expenditure on housing is actually running ahead of apparent demand.

We’re spending billions building new prisons, to incarcerate many more people, when the incidence of crime is falling.

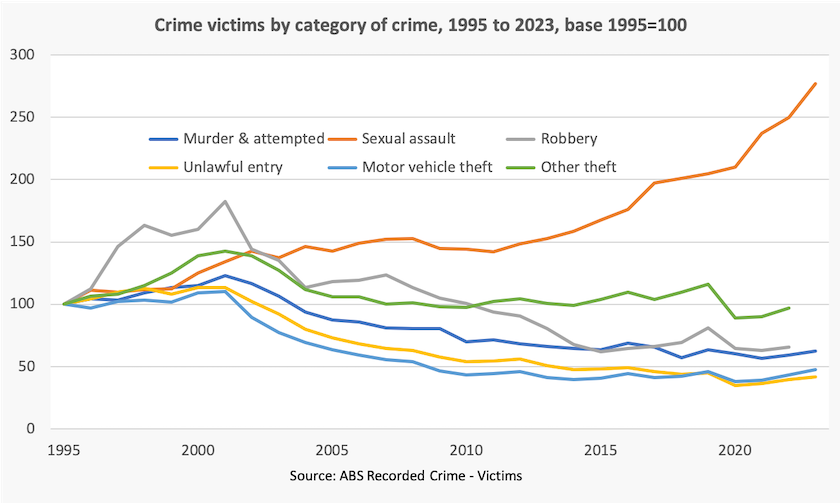

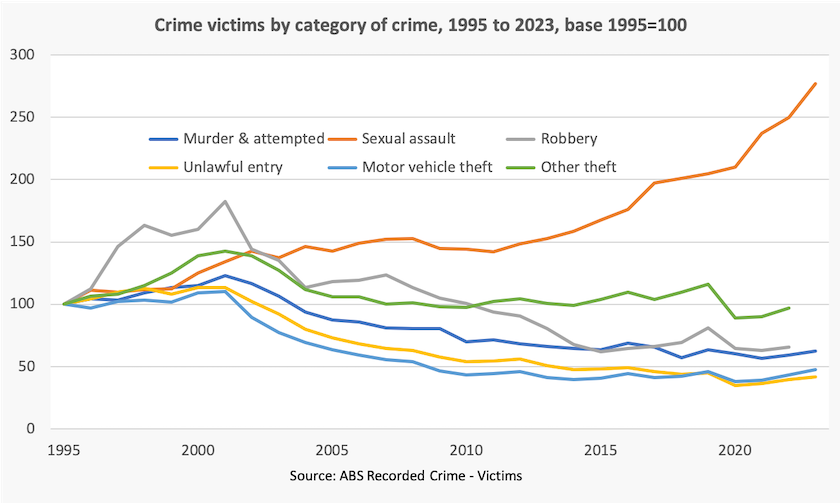

This imbalance is shown in the two graphs below, which is based on categories of crime for which the ABS can construct long and consistent time-series from state data. (Domestic violence, for example, is not included.) The only category of crime that is rising is sexual assault, which is probably explained by much greater reporting. Criminologists generally consider murder to be a good indicator of overall crime rates because it is least influenced by changes in reporting, and the number of murders is definitely falling.

Martyn Goddard in his Policy Post – The great mental health experiment … and why it went so wrong – provides some of the answer. We’re sending the mentally ill to jail.

From the mid nineteenth century until the 1960s, Australia had large institutions, insensitively known as “lunatic asylums”, housing the mentally ill – including many who didn’t really need to be in such institutions.

The “great experiment” was de-institutionalization, which Goddard calls “a 50-year failed experiment”. The ideal was for people with mental illness to be living in “community-based care”, generally involving some form of small-scale supported accommodation.

It worked, for some, but there wasn’t enough of it, and it wasn’t the sort of accommodation that suited everyone’s needs. But there were prisons: Goddard cites figures showing 51 percent of people turning up in prisons have been diagnosed with mental illness. And there were acute-care hospitals, which had to open and expand mental health wards.

The wrong type of public housing: Parramatta Prison

Goddard has written on his post (linked in these roundups) about the way hospitals are accommodating many people who should be in nursing homes. Maintaining mental health wards is another burden on hospitals. His main point is that it is much cheaper, and better for those needing nursing-home care and those suffering mental illness, if they can be provided with their own specialized accommodation. Also, that would free up places in hospitals for acute patients.

So as a result of poorly implemented de-institutionalization, the mentally ill, apart from those who can get access to treatments that allow them to lead normal lives, are distributed between supported accommodation (a fortunate few), jails, acute-care hospitals, and sleeping rough.

Part of the problem probably lies in poor policy coordination. There is also among many mental health advocates a fear of re-institutionalization. But institutionalization is occurring anyway. Jails and the old lunatic asylums have a lot in common.

That goes only some way to explaining the growth in the prison population. Mostly it’s explained by the extension of law’n’order policies, including an increasing tendency by courts to refuse bail, as explained by a group of five academics writing for The Conversation: Prisons don’t create safer communities, so why is Australia spending billions on building them?. They point out, with plenty of evidentiary backup, that while imprisoning people may provide immediate community protection, people eventually come out of prison and re-offend. Imprisonment in itself results in people’s life chances being diminished, and makes a life of crime more likely.

Right-wing populists, offering simple solutions to complex problems, advocate “tough on crime”, “adult crime-adult time”, and mandatory sentencing policies. A fear campaign about crime is easy to run, particularly when the public consistently believe, contrary to evidence, that crime is on the rise.

And there has been a lack of investment in services for troubled young people, particularly indigenous young people. It is quite reasonable that communities find it unacceptable for young offenders go back on to the streets to commit more crime. But it should be equally unacceptable to see young people put in jail. We need other options, that can protect communities while helping troubled young people. Those options involve public investment, which the “tough on crime” populists are unwilling to commit.