Social cohesion and political participation

How representative are our political parties? Not very and becoming less so

The South Australian state electorate Chaffey, covering the area around Renmark and Berri, is pretty safe territory for the Liberal Party: Tim Whetstone won the seat in the 2022 state general election with a two-party preferred vote of 67 percent.

Late last year Whetstone was challenged in a pre-selection. He easily survived the challenge, winning 62 percent of the vote in the Liberal Party branch.

A preselection in a safe state seat is hardly newsworthy, but what is, or should be newsworthy is the small number involved. Only 65 party members turned out to vote in the preselection.

The full story of this pre-election is in an ABC post by Will Hunter Political apathy leaves SA political candidates in the hands of engaged few, in which he reports comment and analysis by University of Adelaide politics professor Clem Macintyre.

Macintyre explains the arithmetic, and it’s straightforward. Membership of the state Liberal Party is only about 5 000, down from numbers in the tens of thousands in past times. Because South Australia has 47 electorates, that suggests each branch of the Liberal Party has about 100 members. On that basis the party faithful of the Renmark-Berri region seem to be a fairly dedicated lot. The only trouble is that there aren’t many of them.

The South Australian Liberal Party hasn’t been enjoying good fortunes lately: it has performed poorly in by-elections against a sitting Labor government, and there are plausible reports that members of Pentecostal churches have been stacking its branches.

Many would consider that what’s bad for the Liberal Party is probably good for Australia, but the more serious issue, as Macintyre explains, is that all political parties in all states are losing membership: it’s an Australia-wide and world-wide phenomenon in democracies.

According to Hunter Fujak of Deakin University, in a 2022 Conversation contribution – The major political parties have a membership problem – the Liberal Party nationally has only 40 000 members, down from about 200 000 in the 1950s. The Labor party does a little better with about 60 000 members. As a back-of-the-envelope calculation, allowing 50 000 for the Greens and Nationals, that suggests membership of our political parties is around 150 000 or 0.6 percent of our population.

By comparison the Chinese Communist Party has about 96 million members, in a population of 1.4 billion. That is about 7 percent of the population. On these numbers one could assert that the CCP is at least 10 times more representative of the population than all the Australian political parties combined, and the same poor comparison would apply to many other democracies. Numbers alone don’t tell us how well those 96 million CCP members represent their constituencies, and it is likely that CCP membership opens up opportunities that membership of the Chaffey branch of the Liberal Party doesn’t. But that doesn’t detract from the fact that our political parties are becoming less representative of the wider population.

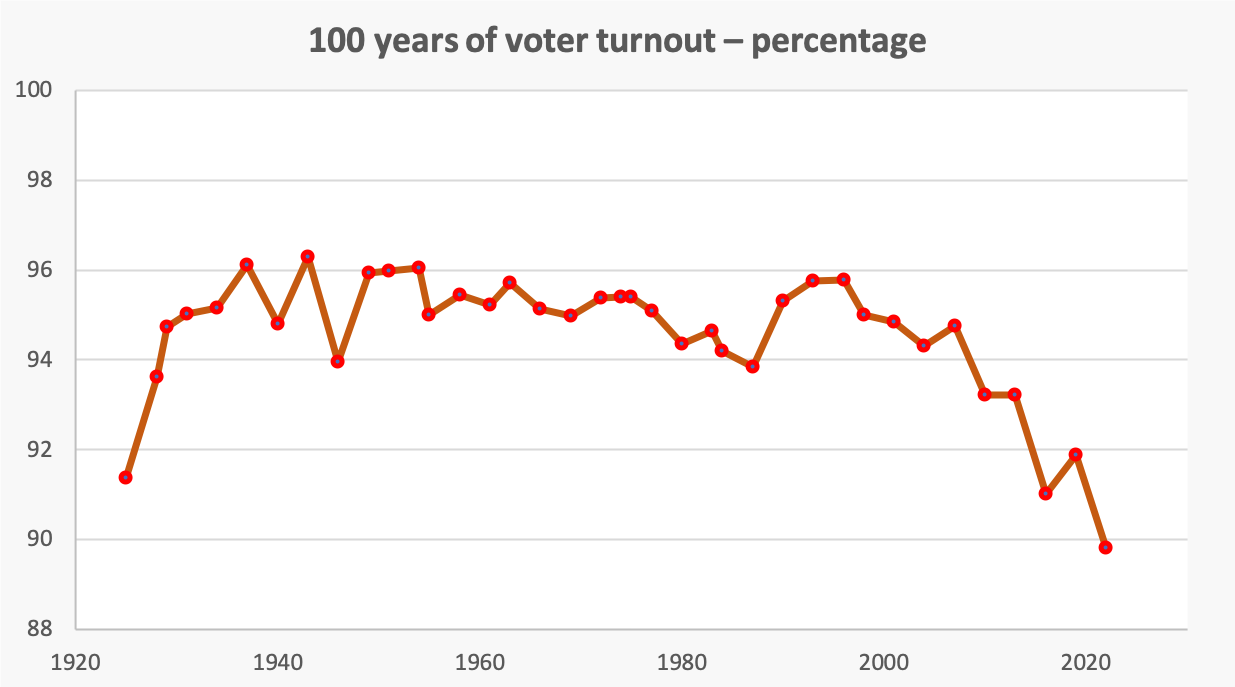

There is evidence that Australians are turning away from political participation, not only in terms of joining parties, but also in voting. The graph below, constructed from Electoral Commission data, shows the percentage turnout for House of Representatives elections over the 100 years since we have had compulsory voting. The fall over this century so far is notable. At around five percent that fall is much larger than the small TPP margins by which political parties have won recent elections.

Low voter turnout could cost the government the seat of Lingiari, which it holds with a one percent margin. Lingiari covers all of the Northern Territory apart from the Darwin urban region. In the Northern Territory election last year there was extremely low turnout at non-urban polling places.

Similarly, the ABS General Social Survey shows a decline in the proportion of adults involved in “civic and political groups”, from 19 percent in 2006 and 2010, to 9 percent in 2019. Unsurprisingly it was even lower in 2020, the year of the pandemic, but there has not been a later survey that might track any possible recovery. The Scanlon Institute’s Social Cohesion Survey, however, suggests that by 2024 “Political participation” had recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

For anyone concerned with the health of our democracy, these hard and soft indicators must be disturbing. Political party membership was never much fun: as Oscar Wilde said “the trouble with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings”.

There is also the problem of “tipping”, as described by Thomas Schelling, and as misunderstood by many popular writers.

We can imagine a party pulled together by people whose politics, on average, are a little to the right of centre. But those whose politics are to the right of the group’s average are just a bit more zealous in turning up to meetings and paying their dues. Those on the group’s left start to drift away, and a positive feedback develops until a party is left with only a hard core on the far right. This is probably what’s happened to the Federal Liberal Party, and the US Republican Party. Many political analysts suggest there was a mirror-image development in the British Labour Party until it undertook the reforms that allowed it to win the 2024 election.

That same dynamic explains why a party branch never recovers from branch-stacking, unless there is some intervention from a higher authority in the party. Unfortunately for the Federal Liberal Party (and for Australia), there is no higher authority that may pull it back from its drift to the far right.

The numbers referred to above relate to what is formally counted, such as attendance at party pre-selections. But we may be changing our forms of political participation, Just in the last week large crowds have turned out at gatherings organized by independents – a form of participation not covered in formal surveys.

Preferential voting, in allowing new parties to flourish, has given Australia an opportunity to compensate for the dynamic of a pair of old, established parties drifting away from the electoral centre. It has also given a leg up to independents whose “preselection” process, if we can call it that, is quite different.

Tim Costello in a MAGA hat: social cohesion in Australia

Is social cohesion at risk in Australia? asks Nick Bryant on Radio National’s Saturday Extra.

Social cohesion is fraying, but it isn’t torn apart, is the answer given by his guests, Tim Costello of the Centre for Public Christianity, and Anthea Hancock of the Scanlon Foundation Research Institute. (16 minutes)

Much of the discussion is about the Scanlon Institute’s 2024 Mapping Social Cohesion Report, linked in the November 23 Roundup. Also Noel Turnbull has a short summary of the Scanlon survey in Pearls and Irritations: Australian social cohesion under threat.

Anthea Hancock interprets the report as a revelation that Australia is remarkably cohesive, downplaying evidence that cohesion is falling.

Perhaps the most positive aspect of that report is that there is high support for multiculturalism, but for most indicators the trend is in the wrong direction, particularly in relation to national pride and a sense of belonging. Australians’ sense of belonging displays a steep age gradient, suggesting that young people see Australia as a land for old men (and women). That’s a fair perception when one considers the effect of policies on housing, student debt, health insurance and taxation of “self-funded” retirees, which strongly favour older Australians.

Contrary to talk about a “cost of living crisis” having developed over the last three years people’s responses on their financial well-being have been fairly stable over the last six years. That doesn’t mean Australians are contented, however. There is declining belief that Australia is a land of economic opportunity; there is a similar decline in belief that hard work leads to a better life; and there is a strong belief that income disparities are too high.

Almost half the people surveyed see “the economy” as the most important problem facing Australia. As concern for “the economy” has risen, concern for “the environment and climate change” has waned, suggesting that many do not understand the close relationship between the economy and the environment: the false idea of a trade-off seems to have traction.

There is discussion about the present wave of anti-Semitic attacks. The survey shows that even before these incidents, Australians’ views about Jews and Muslims were hardening and polarizing around party lines. Those who voted for the Coalition in 2022 have become more negative in their attitude to Muslims, their negativity having risen from 37 to 44 percent. Among voters for Labor and the Greens there has been a rise in negative attitudes towards Jewish people, but much lower – from 6-10 percent to 15 percent.

The Scanlon survey finds that during the Covid-19 period people put a great deal of trust in government. Costello notes that the nation seemed to become more fragmented as each state went its own way on quarantine (probably based more on geography than ideology). At the same time, as shown in the study, many people found more cohesion at their neighbourhood level.

Much of the discussion on the program is about political polarization and the way groups, including the present Commonwealth government and immigrants, have become the scapegoats for the nation’s real and imagined woes.

Costello and Hancock agree that the defeat of the Voice referendum was associated with a heightened sense of political polarization – a polarization that has not abated in the 15 months since the referendum. They acknowledge that there was a great deal of misinformation about the Voice, but no names are mentioned. It’s as if that misinformation mysteriously appeared on the landscape.

Their failure to call out Dutton and his followers for this polarization is understandable. The discussion is about findings, not root causes. Also there is a risk in calling out individuals, because it pushes to the background the social and political conditions that allow right-wing demagogues to arise.

But they missed the opportunity to turn the discussion to the way the “no” campaign trashed norms of civilized political disagreement, which they could have done without naming names. The referendum provided an opportunity for people to put their arguments and views, based on reason and evidence. It wasn’t an election campaign: its success or failure wasn’t going to decide who would occupy the Lodge or sit on the treasury benches.

But one group decided to use the “no” campaign as an opportunity to split the country into two camps – a move straight out of Trump’s playbook. They saw the referendum not as an opportunity to put their views, but as an opportunity to damage Albanese, and took it, regardless of the consequences.

The key event is not the loss of the referendum, but the political process that led to its defeat. If Dutton and his followers had put up reasoned arguments against the Voice, rather than relying on lies and appeals to ignorance, the referendum may still have been lost, but would that loss have left a trail of bitterness and resentment?

That Trumpian process has continued, on issues to do with national security, energy policy, anti-Semitism and immigration – all issues where we need a civilized political argument. We might ask if the Liberal Party is serious about public policy, or if it simply wants to boot out the Labor usurpers and re-occupy the Lodge as an end in itself, rather than to use the election as an opportunity to articulate a coherent policy platform.

We still need a serious public discussion about how we do politics in this country.

And why was Tim Costello wearing a MAGA hat? You’ll have to listen to the discussion.