Economics

Albanese’s economic pitch

It wasn’t billed as a pre-election pitch, but Albanese laid out his government’s broad agenda in his address to the Press Club on January 24.

If you have a spare 75 minutes you can follow the entire presentation. But the first 25 minutes are pretty much as one would expect – a list of achievements and an announcement about support for apprentices. There is a link to a transcript of his prepared speech. (Can the government bring back Don Watson?)

That doesn’t mean those achievements are insubstantial. In the Saturday Paper John Hewson gives the Albanese government high praise for its economic program: Labor’s soft landing is working. Hewson contrasts the government’s economic program with the Coalition’s disjointed economic policy based on spending cuts and a hugely expensive nuclear power plan.

Hewson’s economic credentials are strong – he has a PhD in Economics from Johns Hopkins University and was Dean of the Macquarie Graduate School of Management. And his political credentials are strong: he was leader of the Parliamentary Liberal Party from 1990 to 1994. (Imagine the headlines in the Murdoch media if the political tables were turned, and Keating was writing about Dutton’s economic competence.)

It is notable that 50 minutes of that 75 minutes are devoted to Q&A. He contrasts his own willingness to be scrutinized by the media, with Dutton’s reluctance to face questioning:

He doesn’t like questions, because he doesn’t have any real answers. He’s obsessed with talking Australia down, to try and build himself up.

Albanese’s performance is impressive: it’s worth looking at the video (skipping the speech) to see him fielding questions, including a particularly hostile set of three questions from Geoff Chambers of The Australian (at about 51 minutes), and a solid rebuttal of the Coalitions’ charge that he is “weak” (at about 45 minutes).

Sydney Morning Herald journalist David Crowe has a summary of the session: Three sharp jabs and one blunt question: Albanese fights to win you back.

Inflation – now at two percent, the bottom of the RBA’s band

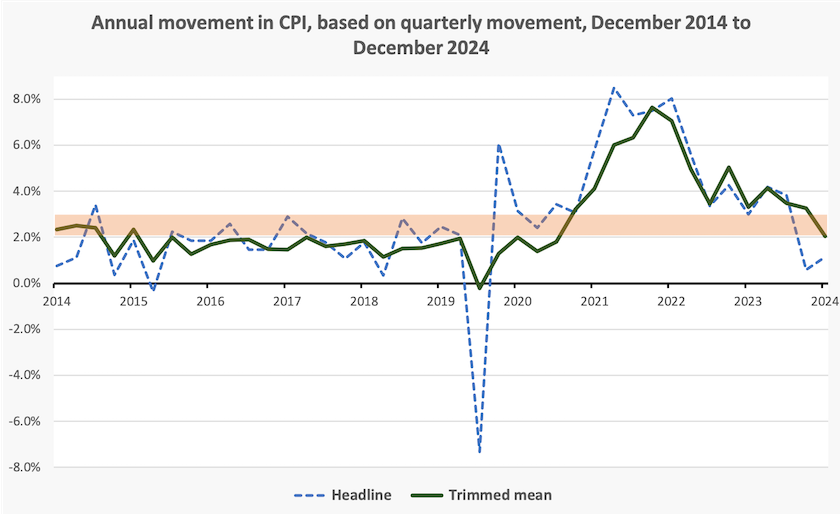

The CPI for the December quarter has come in line pretty well within market expectations. It shows the “all groups” or “headline” CPI to have risen by 2.4 percent over 2024, and the “trimmed mean”, a figure excluding volatile items which some say measures underlying inflation, has risen by 3.2 percent over the period.

A common interpretation of these figures is for journalists and others to write “headline inflation is 2.4 percent”, or that “trimmed mean inflation is 3.2 percent. But those figures relate to the whole year, over which time CPI inflation has been falling. In the latest quarter the headline CPI has risen by only 0.22 percent, or about 0.9 percent (0.22 X 4) if that same rate of inflation were to continue for four quarters. Similarly the trimmed mean has risen by only 0.51 percent, which would come to about 2.0 percent annualized. [1]

These numbers, compiled over one quarter, may have some seasonal factors, but the ABS provides a spreadsheet called “analytical series”, which includes seasonally-adjusted tables for both the headline and trimmed mean series. The graph below shows both series, based on quarterly data, annualized, over the last 10 years, with the RBA’s two-to-three percent comfort band shaded.

The headline movement is very bumpy: that’s why the ABS uses a series that tones down the volatile items. The main point is that inflation, as indicated by the latest CPI data, seems now to be around two percent, at the bottom of the comfort zone.

It will be no time before the Coalition starts warning that Labor has driven the Australian economy into a dangerous deflationary spiral, from which we have to be saved by immediate construction of seven nuclear power plants and a free Toyota HiLux every small business.

The message for those who have a basic understanding of economics is that the RBA should start cutting rates at its next meeting on February 17-18. The ABC’s Michael Janda asks if the RBA has any choice but to cut rates.

1. At these low numbers it’s pretty safe simply to multiply the quarterly numbers by 4 rather than compounding. ↩

We don’t have a “cost of living crisis”, we have an inequality problem

The prevailing idea that we are all experiencing a “cost of living crisis” gives people the impression that we are all bearing some shared sacrifice, distracting us from serious problems of injustice in the distribution of income, wealth and opportunity.

In fact, as pointed out in several of these roundups, there is no “cost of living crisis”. Some Australians, perhaps about a fifth, are doing better than they ever have done before. Many, probably around a half, have seen their incomes stagnate or fall back a few points, but it would be hard to describe that as a “crisis”.

It’s easy to for people to feel hard-done-by. As Ross Gittins points out, financial setbacks, such as higher prices, register more strongly in our consciousness, than financial gains such as tax cuts or regular pay rises: What’s happened to the cost of living is trickier than you think.

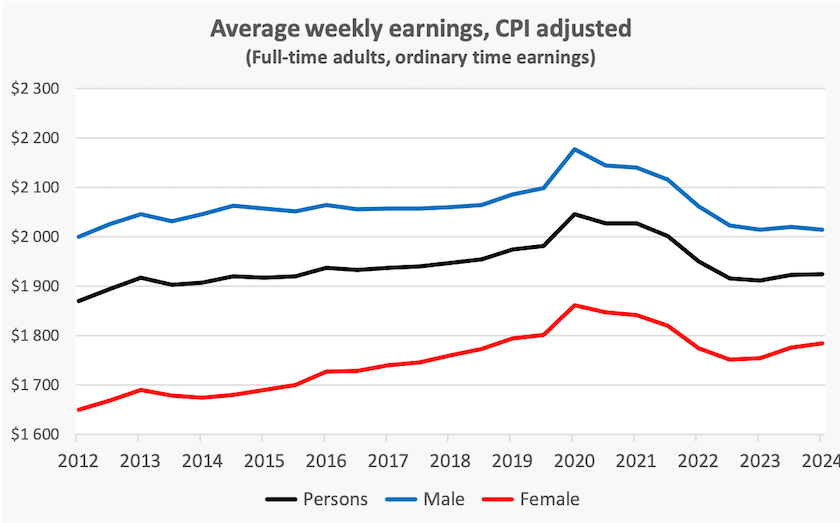

There may also be some gender issues in people’s grizzles. The graph below, constructed from ABS weekly earnings and CPI data, shows movements over the last 12 years in weekly earnings. Men’s earnings are back to where they were in 2012, while women’s earnings are back to pre-pandemic levels. (Explanations probably lie in wage rises in the care economy.)

But another 30 percent or so, including people trying to get by on social security payments, students and young workers who don’t have parental support for accommodation, and people who became financially over-committed when interest rates were low, are having trouble making ends meet. As the ABC’s Daniel Ziffer points out “The economy of 2024 was incredibly uneven, spectacularly unfair and grinding in its relentlessness”. There is a serious and widening generational split, mainly (but not only) to do with housing: 2024 was the Great Divergence as young people copped an economic whack.

The wealth gap

Saul Eslake has a short and data-rich slideshow – Widening the gap – an intergenerational lens on wealth inequality in Australia. While income inequality has remained fairly steady over this century so far, wealth inequality has risen, mainly because our tax system is easy on assets, tough on incomes, and we don’t have an inheritance tax. Intergenerational wealth inequality, therefore, has increased significantly. As Eslake points out, “Older Australians disproportionately have financial assets and owner-occupied property – while younger Australians have most of the liabilities”.

Eslake’s presentation is about the average wealth in each of five quintiles, with around 4 million adults in each quintile. Many people are concerned about these differences because of a sense of fairness, and a concern that those in the poorest quintiles probably don’t enjoy the same opportunities as those in the higher quintiles.

The super-rich

There is another dimension of wealth inequality, relating to the growth of a small number of extremely high-wealth individuals. For example the Forbes rich list has 50 Australians with assets of $1 billion or more.

A group of 270 billionaires has written an open letter to the economic and government leaders gathered at the World Economic Forum, demanding that they introduce wealth taxes to help pay for better public services and to reduce extreme inequality. “Elected leaders must tax us, the super rich. We’d be proud to pay more”.

Billionaire Chuck Collins, one of the signatories, notes that the super-rich have an undue influence in politics. To quote from his article in Fortune, World leaders at Davos need to tax millionaires like me. The fate of our planet and democracy depends on it:

Billionaires made no secret that they funded Trump’s second ticket to the White House to protect and expand their financial interests, whether through tariffs, deregulation, or individual or corporate tax cuts.

…

The ultra-wealthy pose a threat to other facets of our lives besides our democratic institutions. With their extravagant, jet-setting lifestyles, they are disproportionately responsible for fanning the flames of climate change, which contributed to the disaster in Los Angeles. They control what we read, see, and think by owning and purchasing traditional media outlets, social media platforms, and think tanks and academic institutions. And some even manage to single-handedly change the course of history in one fell swoop, as Elon Musk did in September 2022 when he deliberately deactivated his Starlink satellite internet service near the coast of Crimea to thwart a Ukrainian drone attack on a Russian naval fleet.

Their report, Proud to pay more, goes into detail about taxes on the wealthy, and not just the super-rich. For example a survey of people with more than $US1 million in financial assets, a category that would include almost a million Australians, found that two-thirds of them would be willing to pay more taxes “if they knew the revenue would be used to provide better public services, a stronger workforce, and a more stable economy in financial assets.”

Maybe it’s altruism, and maybe it’s a realization that when capitalism replaces democracy with an oligarchy it’s on a fast track to self-destruction.

The public sector has grown – that’s good economic news

“More than four out of five jobs filled in the past two years have been in public service, health and education”.

This is the opening statement in an article by Sydney Morning Herald journalist Millie Muroi: Why a boom in public service jobs has economists worried, quoting economists and others for their views on our economy having been kept out of recession by a fiscal boost.

Among those she quotes there are three views. Some economists are concerned that the public sector is crowding out the private sector: this is hampering economic progress because real value-added jobs are to be found only in the private sector. Some others accept that at this stage of the economic cycle the economy needs a fiscal boost but they see public sector jobs only in terms of fiscal stabilization: they share with more conservative economists the view that they are not real jobs.

The third view is that the services provided by the public sector are of value in their own right. Just as we need food, housing, clothes and cars, provided mainly in the private sector, we also need health care, education, defence and roads, provided mainly in the public sector. The people who provide these are in real jobs.

This third interpretation makes sense – so much sense that it shouldn’t need to be asserted. But it’s an enduring view. In fact the idea that there is no value in public services is specifically stated in the Liberal Party’s statement of beliefs, where it is written that “businesses and individuals – not government – are the true creators of wealth and employment”.

So widespread is the view that government is just some unproductive overhead, that in 2015 Miriam Lyons and I made the case for government in our book Governomics: can we afford small government? – a work explaining the orthodox economics of the public sector, written for non-economists.

In line with his party’s platform, Coalition economic spokesperson Angus Taylor is on record as asserting that as a fundamental economic principle there can be no economic growth unless the private sector is growing faster than the public sector.

Taylor is no economic slouch – he has a Master of Philosophy in Economics from Oxford – but how does he reconcile that view with the fact that in most successful economies there has been a long-term growth in the relative size of the public sector over the last 120 years? That defies the mathematics of his supposed rule.

Why the relative size of government grows

The explanation for the relative growth of the public sector is straightforward, and was explained by economist William Baumol in the 1960s. Technological progress has brought huge productivity gains in the production of goods, but many services remain intrinsically labour-intensive. Think of the real price falls in cars, electronic equipment and so on, and contrast that with the stable or rising price of a haircut or the services of a plumber. Because of various limitations of markets (“market failure” in economists’ terms), the public sector has many services which remain intrinsically labour-intensive. These include health care, education and policing.

If, over time, we are to sustain the same level of publicly-provided health care, education, policing and other government services, the relative cost, and therefore the relative size, of the public sector has to grow, even if there is no expansion of government into new areas.

Besides this productivity-induced change, known as the “Baumol” effect, there are two others drivers of a larger public sector. One is ageing: what we save in education costs is not enough to offset the higher costs of health and disability care. Another is that as our needs for private goods becomes satiated, we are likely to start demanding more collective goods and services. As people’s material living standards improve, they are more likely to become more willing to share their fortunes with others.

Of course there is always a push for improved efficiency in the delivery of public services, but we only need to consider the reaction to Robodebt to see the limits. We want teachers and health care professionals to have labour-saving technologies, but we also want the human service. AI is one of those technologies, but it will not displace humans in the foreseeable future.

The DOGE movement

From a safe distance we can observe an experiment in progress in the USA, as the Trump-Musk administration pushes through with its DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) initiative. Harvard’s Kennedy School asked ten of its faculty to describe how they expect to see DOGE turn out. Their predictions vary, but there are general themes. It is easy to cut: you just have to sack people and cut off appropriations. There are savings to be made, and parts of the bureaucracy are top-heavy and encumbered with practices that hold back productivity improvements, but it’s easy to over-estimate those savings, and many services are already cut to the bone. That means substantial savings can be made only with deep cuts to services. Public opinion surveys reveal that people consistently over-estimate the bureaucratic size of the public service. There are too many TV programs about ministerial staff and not enough about Centrelink workers.

Dutton has not hesitated to jump on to the DOGE bandwagon. In fact he is trying to outdo Trump by proposing to appoint two government waste ministers, but he struggles to identify any “waste” he would cut. Jacinta Nampijinpa Price is on the job however: her proposal to abolish Welcome to Country ceremonies would save every taxpayer 1.5 cents a year.[2]

The opposition has had a superficially attractive message based on the expansion of public service employment and on the expansion of jobs on the public payroll since the Albanese government was elected. The figure of 36 000 is now being thrown around as the target for job cuts.

The trouble, as Finance Minister Katy Gallagher explains, is that most of these jobs are in direct service delivery. The government is making slow progress in improving service delivery times – everything from Centrelink payments through to new passports. It is filling vacant positions in home affairs and policing. Any cuts would have immediate consequences.

Not all those public service jobs are in direct services. Some are in areas such as policy analysis and research, where the Albanese government has been bringing functions previously outsourced to highly-paid consultants into the public service. The immediate cost savings are clear but that is not the only reason for bringing work back in-house.

The longer-term benefits are in terms of re-establishing a professional and capable public service, with established expertise. For many reasons to do with time-horizons and commercial incentives, consultants can never take the place of a professional public service. Loss of public service capability has been one of the causes of poor administrative decisions over the years since contracting out became the norm.

The issue of public sector capability is one that should transcend the small-government/big-government debate, because it starts with the question “is our public service capable of doing the job we expect of it?”

As soon as anyone admits that the public sector is failing in some way, however, right-wing opportunists jump in advocating cuts and privatization, and as a defensive reaction unions and others with a stake in the public service close ranks and a stalemate develops.

Joe Walker has drawn our attention to work by the Niskanen Center, and its concern with strengthening the state’s administrative capacity. It’s in a US context, but its way of thinking is relevant to any country. The public sector is a vital part of our economy, and we should strengthen its capability. Not a radical idea, but it’s a long way from those who see the public sector as an intrinsically inefficient overhead, and it cannot be placed on some left-right spectrum.

So far the Albanese government has been able to accommodate an expansion of the public service without contributing to the deficit or to inflation. But it has to face the fact that Australia has a public sector that is almost the smallest out of all “developed” countries, and that just to sustain existing services will require larger outlays. It has to collect more revenue.

There is a risk that in the election campaign the Albanese government will allow itself to be backed into a corner, promising tax cuts or “no new taxes”. That would leave income tax bracket creep as the fall-back for tax collection, pushing meaningful tax reform another three years down the track.

2. The Coalition claims that Welcome to Country ceremonies have cost $450 000 over two years. Divide that by two for an annual cost, and divide it by 15 million taxpayers. ↩

Dutton’s feudal fetish

It is hard to shake Australians from certain beliefs that persist in the absence of evidence, such as the belief that family violence occurs only in poor and uneducated families, or that Coalition governments are competent at economic management. The most recent Resolve Poll, reported by Adrian Beaumont in The Conversation, finds that the Liberals lead Labor by 42 to 23 percent on economic management.

The latest instalment of Coalition economic idiocy is Dutton’s proposal for small businesses to provide meals and entertainment for employees and business associates without incurring fringe benefits tax. It’s clever, because it benefits not only small businesses taking advantage of the breaks, but also the thousands of cafes and restaurants at risk of going under because of Labor’s mismanagement. So the justification goes.

Writing on Michael West Media – Sir Lunchalot Dutton and some uncomfortable truths – Michael Pascoe demolishes this bit of misinformation, and Michael West himself, in his regular scamwatch, details ways the scheme can be rorted.

Crispin Hull, in his post – Dine out on this pathetic tax policy – reminds us that 40 years ago the Keating government got rid of this rort.

Proposed lunch tax deduction to hurt productivity, warns Eslake is the headline of Michael Read’s Financial Review article covering the policy.

Saul Eslake has been a consistent critic of the “fetish for small business” that has seen a swagful of unjustified breaks for small business, distorting resource allocation.

In increasing demand for restaurants and entertainment venues the policy would be inflationary. Prices in those restaurants and entertainment venues would be set by business clients, making them more expensive for lesser mortals who do not have expense accounts.

Corporate perks also have an anti-competitive effect. The free lunch and the invitation to the VIP box at the football carry an implicit obligation, as every salesperson knows, biasing beneficiaries of hospitality from assessing bids on the basis of value-for-money.

As Bernard Keane writes in Crikey, Dutton’s business lunch idea takes the piss out of the entire notion of worthwhile public policy.

The strongest revelation of the Coalition’s warped way of thinking is in Read’s statement that “Mr Dutton has billed the measure as a way for employers to take their staff out to a venue to celebrate a milestone event or acknowledge their hard work”.

This is Dutton’s master-servant view of business. It’s about the boss rewarding the underlings, who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford such luxuries. Compare that with the Friday afternoon pub session, where everyone chips in, regardless of their rank, because they are all motivated by the value of the work they are doing, rather than the boss’s paternalistic incentives.

Dutton, like so many of his colleagues in the Federal Liberal Party, is trapped in a feudal time warp.