The Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook

Here’s where they prepared all this stuff – Treasury building Canberra

The much-awaited MYEFO

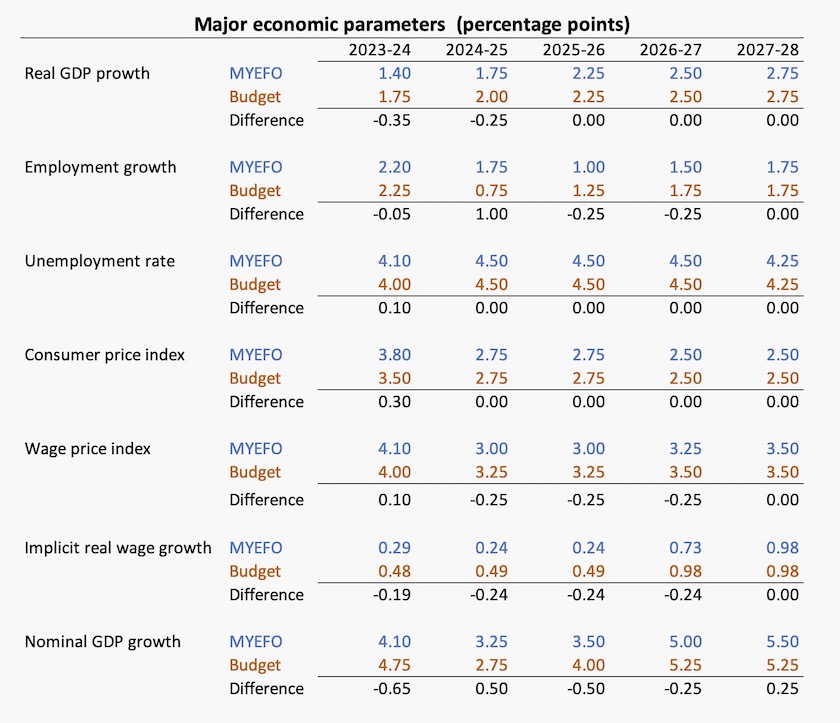

Most media attention is directed to the fiscal outcome and projections of the MYEFO, as if balancing cash out and cash in is the be-all and end-all of economic management (if only it were so simple!). But the most important aspects of the MYEFO are what is says about economic outcomes and projections. These are shown below, with the figures presented in the May budget (in red) for comparison. The significant updates are in GDP growth and employment.

It paints a picture of a weak economy. Even the small GDP growth predicted in the last two budgets hasn’t eventuated. Those budgets predicted small real wage rises of about 0.5 percent, but wage growth is now predicted to be even lower – around 0.2 to 0.3 percent. This a sign of an economy struggling to lift productivity.

Note that the unemployment rate is predicted to remain at around 4.5 percent. The economy is weak, but that weakness is not expected to be manifest in high unemployment. Nor is there any expectation that this comparatively low unemployment rate will boost inflation, which is forecast to remain well within the RBA’s two to three percent comfort zone. Treasury is clearly more confident than the Reserve Bank that we can have low unemployment without causing inflation.

Fiscal forecasts

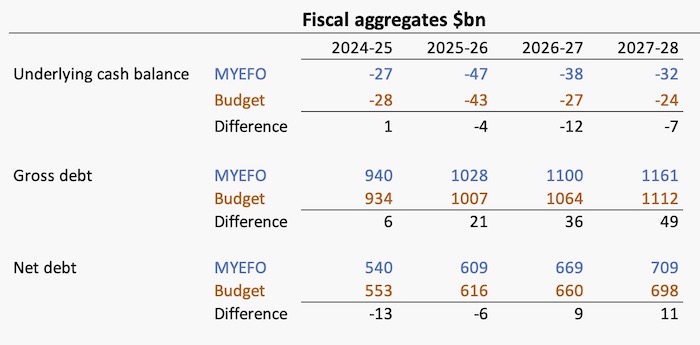

The MYEFO fiscal figures, compared with those in the May budget, are shown below. There are also projections out to 2034, but these, like the Coalition’s plan to spend hundreds of billions on nuclear power, are over the horizon in fantasyland: they are best disregarded.

Fiscal forecasting is politicized territory, evoking hyped-up language about a $22 billion budget “blowout” to quote one ABC newsreader.

That $22 billion figure is obtained by adding the difference between the budget and MYEFO fiscal balances over the next four years. It’s no big deal. The reality is that the deficit remains in the zone of 0.8 to 1.5 percent of GDP. It’s a typical range for Australia, and in comparison with other countries this is a small fiscal deficit – one of the lowest of all “developed” countries. (The only countries now running significant fiscal surpluses are Denmark and Norway, which says something about the economic strength of Nordic socialism.)

Because of “emerging challenges in the Chinese economy” affecting commodity prices and volumes, expectations of company tax receipts have been revised downwards. Nevertheless the outlook for receipts is up over the period of projections, by about $20 billion. That’s probably because inflation is causing some creep in the income tax steps. But payments are up as well, by about $42 billion over the same period. Between them they account for the $22 billion rise in the cash deficit.

John Hawkins of the University of Canberra has a Conversation contribution on the MYEFO – If Treasury forecasts are right, it could be a decade before Australia is “back in black”. He notes that it has substantial projections for “decisions taken but not yet announced”. That’s Treasury shorthand for money set aside for promises to be made in an election year.

The ABC’s Tom Crowley also reports on the MYEFO – Gloomier economy to shape election as government spends another $19 billion – revealing some other details, including increased spending on childcare.

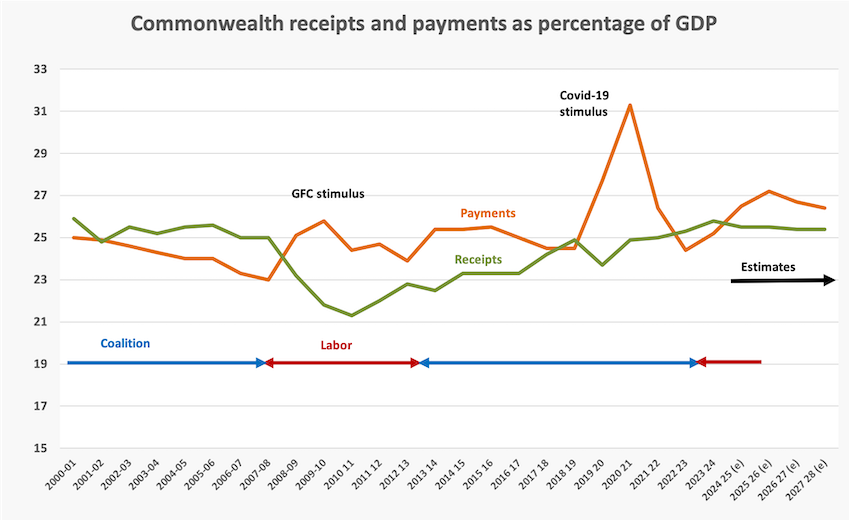

These figures and articles are about the short term. A longer-term perspective, covering this century so far, is in the graph below. If one ignores the Covid stimulus, it’s clear that there is a trend for government outlays, as a percentage of GDP, to rise. That’s understandable in view of the skilled-labour intensity of many government services, a slowly ageing population, and increasing outlays on defence. Receipts (90 percent of which are from taxation), have not risen to catch up with payments.

To her credit the ABC’s Sally Sara has been almost alone among journalists in challenging the government to explain why it has largely neglected tax reform. Finance Minister Katy Gallagher, in response to Sara’s challenge, pointed out that the Coalition and the Greens have blocked legislation to raise taxes on high-wealth retirees, but these are only small measures.

The overall impression one gets from the budget is that there is little the government can do, or could have done over the last 30 months, to improve the economy. The Albanese government took over from predecessors who, over a long period, neglected the task of structural reform, failed to invest in hard and soft infrastructure, and neglected to pursue a necessary energy transition. In this weakened economy the Coalition’s Covid spending boost caused a spike in inflation, and the Reserve Bank’s irresponsibility in holding interest rates too low for too long fuelled housing-cost inflation and a rise in household debt.

The government has also had to deal with a serious backlog in spending on services in the care economy – in health, child care, veterans and aged care. When the government says that most of its increased spending is largely outside the government’s control, this is not just political spin. The Australian people demand that the government attend to these needs, as Shane Wright of The Age-Sydney Morning Herald points out in his article It might look like Chalmers is spending like a drunken sailor, but this is what’s really going on.

Politically people need to shake the belief that the Coalition would do better. In fact the few policies the Coalition has announced suggest that it would subject the country to an austerity budget with consequences for the care economy and education, it would resume its program of reducing real wages, and it would stymie progress towards the country’s energy transition (if its nuclear plan is to be believed).

The slightly expansionary budget approach revealed in the MYEFO seems to be appropriate for an economy with no growth and little risk of inflation. An increased deficit of $22 billion over four years is not a problem, but the need to raise more revenue over the medium to long term is a problem, and the government can do something about it.

There seems to be plenty of opportunities to raise more tax, particularly from the well-off, who are unbothered by the so-called “cost of living crisis”. Those opportunities lie in the revenue the government isn’t collecting because of various concessions, covered in the next section on Treasury’s Tax Expenditure and Insight Statement.

Treasury’s new budget document – the Tax Expenditures and Insight Statement

This year’s Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook was preceded by a new Treasury publication, the Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement. In short, it “highlights revenue the government does not collect due to certain tax expenditures”.

For those unfamiliar with the term Tax expenditures, Treasury states:

A tax expenditure arises where the tax treatment of a class of taxpayer or an activity differs from the standard tax treatment (tax benchmark) that would otherwise apply. Tax expenditures can include tax exemptions, some deductions, rebates and offsets, concessional or higher tax rates applying to a specific class of taxpayers, and deferrals of tax liability.

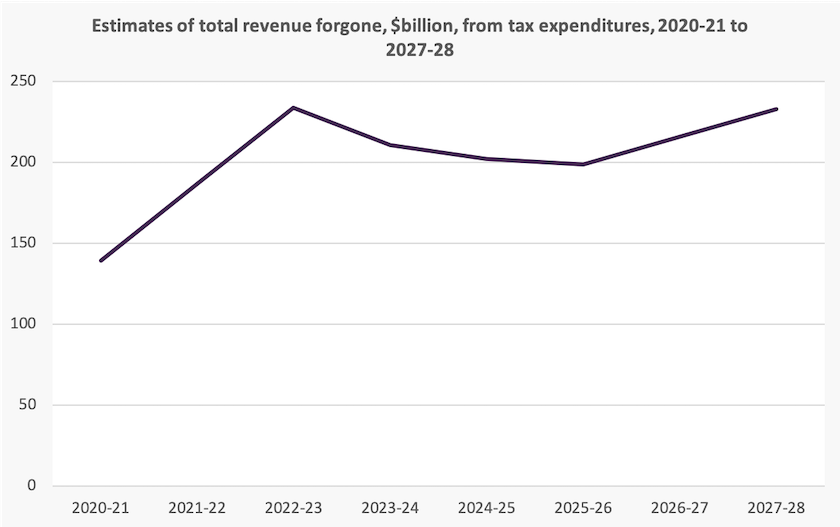

Tax expenditure statements are a regular aspect of budget documentation, with estimates of revenue forgone as a result of the application of 51 concessions (such as those applying to superannuation), and 7 areas of extra revenue gained because of certain extra tax payments (such as the Medicare Levy Surcharge).

The total cost to revenue of tax expenditures is estimated to be $202 billion this year. They rose particularly strongly during 2021-22, the last full year of the Coalition government, and a quick scan of the figures suggests that much of this growth was in concessions for businesses and trusts.

To put that $202 billion into context, total government receipts this year are about $700 billion. Tax expenditures are a significant aspect of our tax system, particularly our income tax system.

As in other years, the biggest tax expenditures relate to superannuation: $31 billion a year for concessions on contributions and $24 billion for concessions on superannuation earnings. Other large tax expenditures include exemption of people’s main residence (the “family home”) from capital gains tax, family trusts, and work-related expenses.

A simple, but wrong, interpretation is to consider all tax expenditures to be rorts. Some, such as the $2 billion for child care services, are designed to make the tax and transfer system fairer.

This new document includes a distributional analysis for 16 tax expenditures. There is a huge amount of data for public finance nerds avid analysts. Three examples, without any claim that these are the most important, follow.

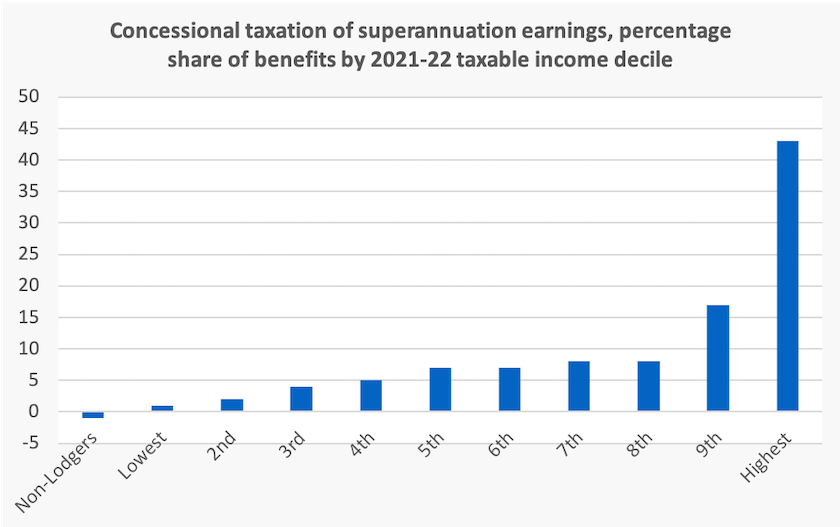

First is a chart of the distribution of benefits from concessions for superannuation earnings, showing that 43 percent, or $10 billion of those $24 billion of benefits, go to the top 10 percent of taxpayers – predominately well-off “self-funded” retirees. (Because for many their superannuation accounts have been funded by concessional contributions and inheritances, the term “self funded” is a misnomer.)

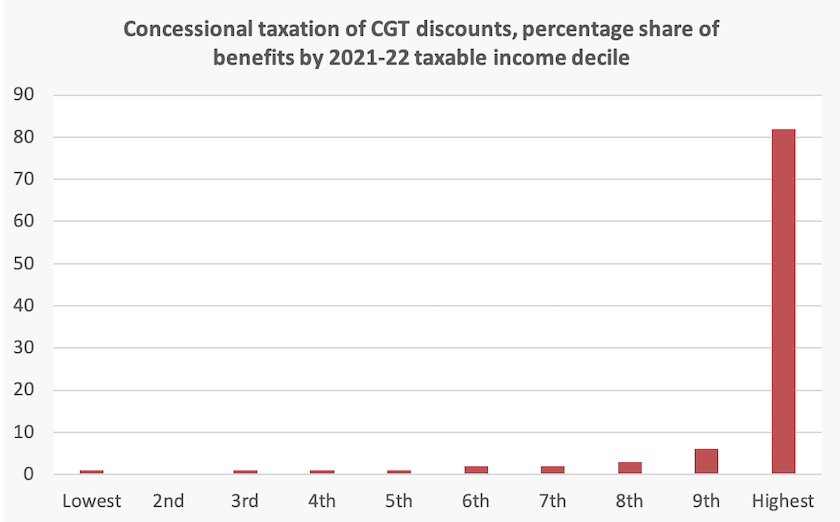

Second is the distribution of capital gains tax discounts, showing that 82 percent of those benefits – about $18 billion – goes to the top 10 percent of taxpayers.

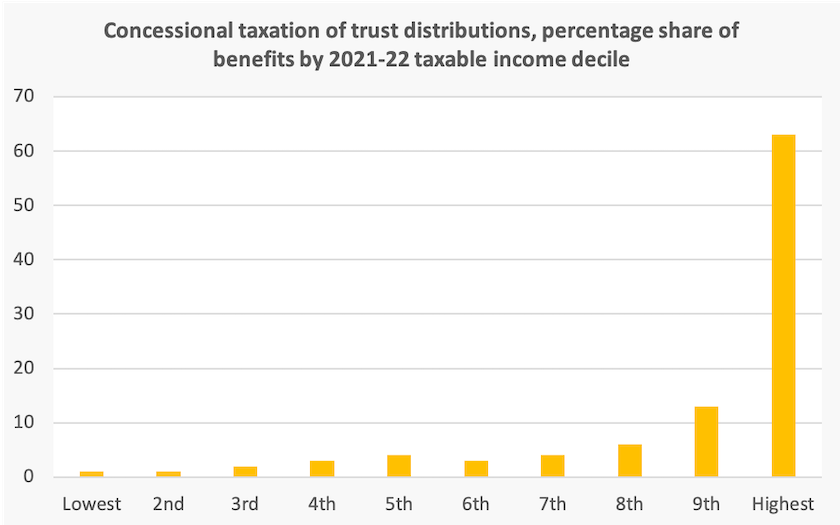

Then there is the concessional treatment of trusts, the tax-avoidance mechanism favoured by small business who distribute earnings to family members on low marginal tax rates. The chart below tells only part of the story, because it relates to the $67 billion of trust income declared by taxpayers, while many trust beneficiaries do not have to lodge a tax return because their income is below the tax threshold.

These three charts suggest that there is something inequitable about our tax system, but simply showing that some benefits go disproportionately to the most well-off does not lead to the simple conclusion that they should be abolished.

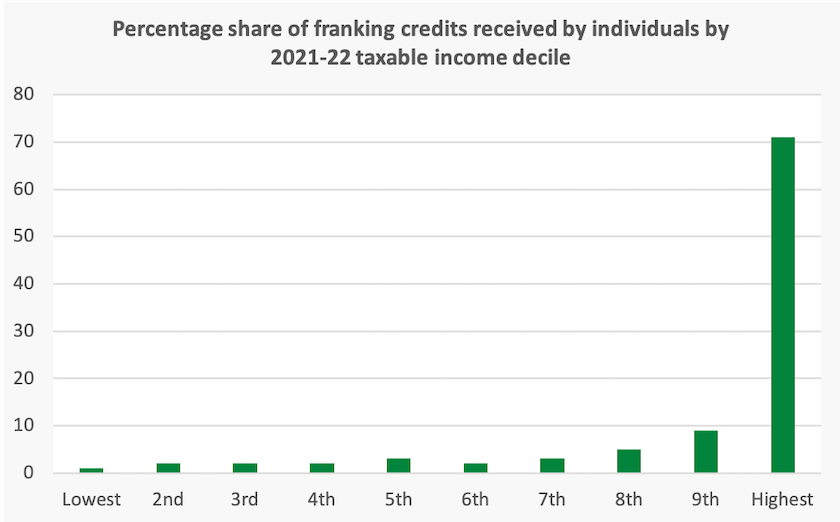

For example another chart shows the distribution of $23 billion of franking credits to individuals, and this appears to be highly inequitable. Just since the Treasury’s document was released there have been suggestions that the government should disallow refunds of franking credits.

But franking credits are simply refunds of tax already paid by corporations. They benefit the very well-off because these include wealthy self-funded retirees paying zero or at most 15 percent income tax. Rather than abolishing franking credits, as the Labor opposition proposed in 2019 (to its unnecessary political cost), it would be more equitable and would collect far more revenue if the income of those retirees were taxed at normal income tax rates.

Franking credits allow Australia to maintain a high company tax rate for foreign owners of companies, while keeping the effective tax rates for Australian owners of companies down around 15 percent. They encourage investors to put their funds into equities: abolition of franking tax credits would see many of those funds diverted into housing speculation, which most would agree is undesirable.

This is a cautionary tale to wannabe tax reformers, warning them not to focus on any one tax expenditure or other concession, without considering the whole range of taxes and transfers and their interactions, as has been the consistent message from reformers such as Ken Henry and Ross Garnaut.