Public ideas

The lucky country 60 years on

“Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck”.

That’s a quote from Donald Horne’s 1964 book The lucky country, a critique of the Australia he saw at the time – country that was provincial in national character and weighed down by a cultural cringe.

On the ABC’s Saturday Extra Nick Bryant interviews Ryan Cropp, author of the 2023 book Donald Horne: a life in the lucky country.

The interview – The Lucky Country turns 60 – is about whether Horne’s 1960s portrayal of Australia, and his warning that our luck can run out, is still relevant today.

The Lucky Country is still in print. That suggests something about its relevance. It is notable that Horne was critical of our two main political parties for their lack of imagination and their complacency. That was prophetic.

Bryant and Cropp point out that much has changed in 60 years – there was no such thing as “multicultural Australia” in the 1960s, and the White Australia policy was in force. There was a cowering, almost reverential, attitude to Britain and its practices. They reassure each other that we have come a long way since then.

But have we?

We have been too fearful to take on two constitutional changes that would have re-defined how we see ourselves – one on severing constitutional links with the UK, the other on recognizing the original owners of this land. Our national broadcaster maintains a large office in London, and fills its television programs with English shows. Our nominally Labor government invites the King of England to make a state visit.

Our economy is still an extractive one and one of our main political parties believes we should stay that way. We still see land speculation as the path to personal prosperity. We are still the same cultural philistines, preferencing “job-ready” training to a liberal education.

Overlooking our unique natural endowments, we look to other countries for models. Nowhere is this more evident than in the idea that we should build nuclear power stations, because other countries have them and we’re not clever enough to forge our own way to net zero emissions.

Donald Horne may be rather disappointed if he came back today, but at least his message has stuck with some. It would be remiss of me not to mention two books, inspired by Horne’s work, published by the Centre for Policy Development: More than luck: ideas Australia needs now, edited by Mark Davis and Miriam Lyons (2010), and Pushing our luck: ideas for Australian progress, edited by Miriam Lyons (2013).

Do partisan voters really inhabit separate realities?

Writing in Inside Story, Peter Browne describes experiments testing the strength of people’s adherence to false facts: Is that a fact?.

One experiment asked people to provide their estimates of basic economic facts, where there were likely to be partisan differences. There were questions on issues such as the number of immigrants, the rate of inflation and so on. People’s responses reflected partisan differences, confirming the idea that people on the left and on the right live in worlds of different facts. But when people were offered incentives to answer correctly, or to admit that they didn’t know, partisan differences diminished significantly.

(These findings confirm university lecturers’ everyday experience: the reward of a grade tends to eliminate partisan bullshit in students’ assignments.)

This has implications for opinion surveys and polls. When people are surveyed on their beliefs, there is a probability they will provide answers that fit their political perspective, rather than their considered views. We should be careful, therefore, in interpreting polls that show wide partisan divisions. Browne illustrates this with a poll about immigration where people’s perception shifted in response to statements by Peter Dutton.

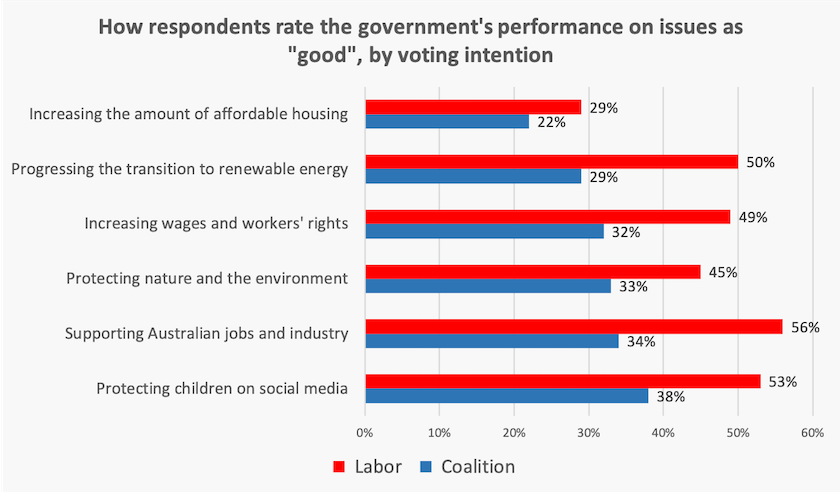

To take a current example where partisan differences may be over-reported, the most recent Essential poll asks respondents to rate the government’s performance on six issues. Responses to those issues, by voting intention (two main parties only), are shown in the chart below.

The partisan differences are clear. The responses on renewable energy and workers’ rights at first seem to be counterintuitive. It is probable that loyal Coalition voters would think the government is prioritising these issues when they shouldn’t be: the rational, informed Coalition voter would think that the government should be directing its resources elsewhere, but he or she would accept that it is doing a good job on these issues. But it seems that Coalition voters are primed to believe everything the government does is bad.

When opinion polls on issues simply reveal partisan prejudices they aren’t very useful for guiding policy.

The perennial ambiguous opinion poll question is “do you approve of the way X is doing his/her job?”. Many people, observing Morrison’s performance in the 2022 election campaign, believed he was doing an excellent job in making himself unelectable.

Opinion polls are tricky: statisticians don’t like them.

Reversing the democratic recession

Two political events have surprised the world in the past few weeks – the election of Donald Trump in America and the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria. Because one involves the elevation of an anti-democratic strongman, and the other involves the deposition of an anti-democratic strongman, we might believe that they conform to no known pattern. But one thing they illustrate is the way regime changes can take us by surprise.

That is one of the messages in Larry Diamond’s Foreign Affairs article How to end the democratic recession: the fight against autocracy needs a new playbook, written in late October before Trump’s election.

He notes that the rate of democratization in the world reached a peak late last century at the end of the Cold War, but over this century so far the trend is towards authoritarian regimes displacing democratic regimes. “The global outlook for democracy is clouded, if not downright disheartening. Political extremism, polarization, and distrust have been on the rise even in long-established liberal democracies”, he writes.

He gives many reasons for this reversal: elections are easy to manipulate in countries that don’t have a bedrock of institutions such as the rule of law; economic and social problems in democracies have been on display to the world while some autocracies, most notably China, have shown huge success in improving living standards; politicians on the right have been able to use social media to their advantage; fear campaigns have flourished; and some dictators simply seem to be very skilled.

But he goes on to outline ways apparently solidly-established autocratic regimes can be defeated. These regimes often experience moments of weakness which can be exploited by a well-organized opposition. Opposition groupings should come together as a single movement and be ready for that moment – they can sort out their differences once they have established a democratic order.

Populists’ path to political power

The well-established explanation for the success of right-wing populist parties lies in the idea that globalization, immigration and other drivers of economic change have left many people behind. The public’s growing support for populist solutions have helped elevate people like Trump, Erdoğan and Orbán to power.

Writing in Foreign Affairs – The populist phantom: threats to democracy start at the top – Larry Bartels of Vanderbilt University rejects this “bottom up” explanation. He finds that there is very little relationship between people’s support for populist ideas, and the success or otherwise of right-wing populist parties.

Right-wing populists generally succeed on the basis of specific factors, most often the poor performance of governments. (That’s in line with the aphorism that oppositions don’t win elections; rather governments lose elections.)

He notes that right-wing populists generally go about cementing their power by weakening democratic institutions. But this is generally of little concern to voters, apart from those with high levels of education. “Ordinary people in most times and places have cared more for their security, their personal finances, and the validation of their social identities than they have for the upholding of democratic norms and procedures”.

Unfortunately, history confirms that assertion. People don’t pay much attention to their governments’ drift to authoritarianism and their destruction of power-limiting institutions, until they are rounded up and put in concentration camps. By then it is too late.

Bartels sees strength in multi-party democracies, such as those in mainland Europe, where right-wing populists have been making small gains in recent years, (the media tend to overstate their gains), but they generally don’t make it into office because other parties form coalitions or minority government working arrangements to exclude the far right from executive power.

That proposition is being put to the test in France right now, and it may be put to the test in Australia next year.

Bartels is author of the book Democracy erodes from the top: leaders, citizens, and the challenge of populism in Europe.

Learning from populism

It’s accepted wisdom that politicians elected on populist platforms will do harm to institutions upholding the global order. Right-wing populist governments are well known for their scorn of UN and other institutions and their tendency to withdraw from multilateral agreements.

Writing in Open Forum Jolyon Ford of ANU acknowledges that view, but he does not believe they necessarily damage those institutions. His article – a kick up the pants – suggests that some of the criticisms coming from the right can force institutions to reform, and they may help mobilize people to come to the defence of those institutions.

Ford is author of Human rights and populism, a work that examines the reasons institutions established to provide fundamental protections for all, become scapegoated for promoting “us and them” divisions and for representing the interests of small, often foreign, minorities”.