Other economics

National accounts

The Reserve Bank seems to be succeeding in its mission to smash the economy. The headline figures from the ABS tell most of the story: GDP over the last quarter rose by only 0.3 percent, bringing growth for the year to 0.8 percent.

Lower commodity prices saw our terms of trade fall, contributing to falls in activity by the mining and manufacturing industries. Our GDP was kept in positive territory by public spending – capital spending mainly on transport infrastructure by state governments and recurrent spending on health care, child care and education.

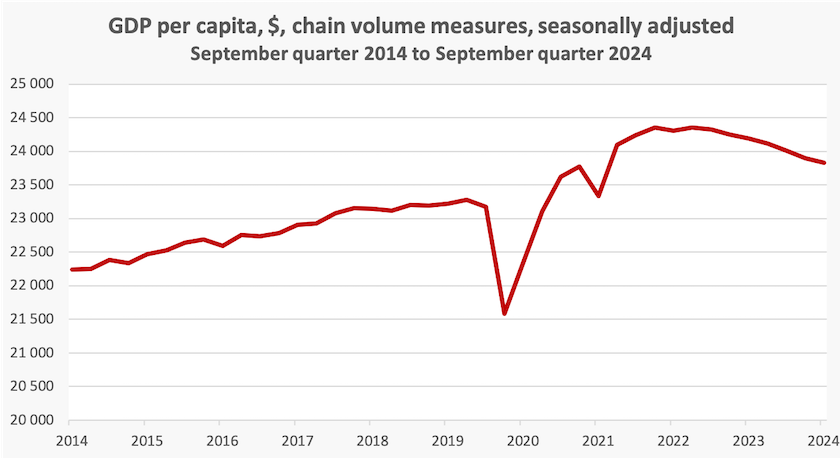

Much of the story of our economy is captured in the graph plotted below – our GDP per-capita in constant prices.

The short-term story – the partisan story told by the Coalition, by partisan media, and by lazy journalists who talk about “a cost-of-living crisis” is that our GDP per-capita peaked in June 2022, just as the Coalition was handing over a healthy economy to Labor, and has since fallen by 2 percent. There have been seven consequent quarters of negative per-capita economic growth. That would count as a “prolonged recession” in any country that didn’t have Australia’s population growth.

That’s all correct, but it’s in a partisan frame.

The longer story is that per-capita GDP, after strong growth earlier in this century, almost stopped growing in 2017. In 2020 the pandemic hit, and for a couple of years the numbers made little sense. It’s now clear that that rapid rise up to 2022 was due to loose monetary policy over a long period (which led to many households taking on too much debt), and excess fiscal stimulation during the pandemic.

A freehand line drawn along that 2017 to 2019 period, projected out to the present, suggests that we are probably now back to that trend of glacially slow growth. The government’s fiscal caution and the RBA’s aggressive monetary policy have probably compensated for that stimulus.

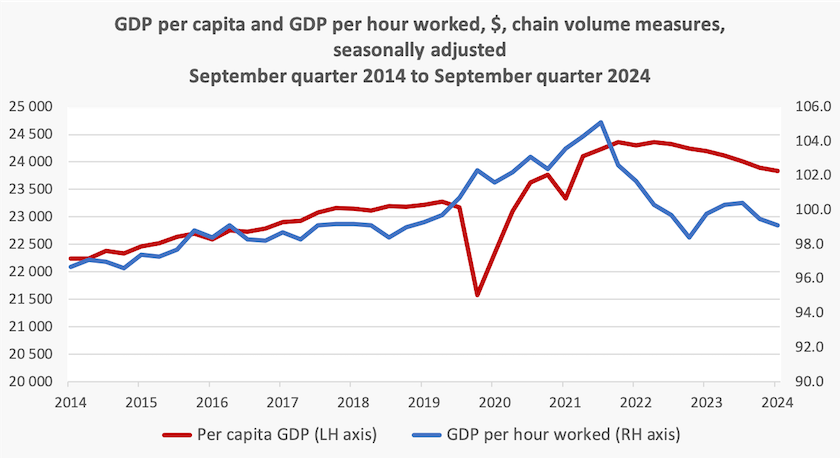

That slow growth is influenced by many factors, but none are more important than productivity, and over the long term (once changes in terms of trade even out) GDP and productivity as indicated by GDP per hour worked, should track together.

When they are plotted together, as shown in the next graph, we see that they did track together, until the pandemic hit. Then there is the weird phenomenon of productivity rising quickly as the denominator (hours worked) fell, before falling back, as more people came back to the workforce.

The slump in productivity around 2017, is due to many factors: a long period without structural reform, the Howard government’s 1999 changes in capital gains tax that privileged speculation over patient investment, inadequate investment in training and infrastructure, privatization, and weak competition policy. What happened during and after the pandemic is much less clear, but the Productivity Commission is looking into it and is promising to give us an explanation next month. It should make for gripping holiday reading.

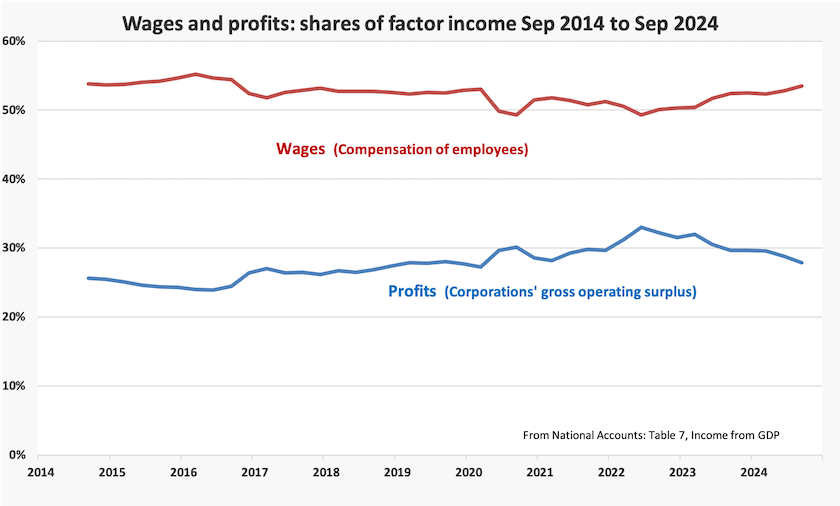

One time series overlooked by the commentariat is about the shifting share of profits. The wages share of GDP had been on a long-term decline, from about 60 percent in the 1970s and 1980s, to 50 percent in this century. The graph below shows how it has picked up in the last two years. The present government’s policies have probably contributed to this recovery.

The other story in national accounts, often missed, is about inflation. Notably the GDP chain price index – an indicator of economy-wide inflation – fell by 0.2 percent. This is a strong indicator that the economy is in a state of deflation. Yet the Reserve Bank insists on using the household consumer price index as its only inflation indicator – an error that would see a first-year economics student awarded a “resubmit” grade.

The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens, explaining the National Accounts figures, points out that the Reserve Bank has almost certainly over-estimated the economy’s growth rate. Will it admit that it got its estimates wrong and cut rates when it meets next week?

Public services: Gina Rinehart’s advice to the Coalition

Don’t knock the people who work here – we need them

The national accounts show that but for government spending the Australian economy would have gone backwards.

It is strange that some see this contribution from government spending as problematic, implying that building roads and metro systems, caring for children and treating the ill is somehow less worthy than buying coffee, losing money on pokies and spending on bank fees – all of which show up as private activity in the GDP. It is indicative of a weird moral framework, particularly among Coalition politicians who assert that the government should cut spending.

Writing in the Saturday Paper, Karen Barlow reports that the opposition is on a crusade to cut public spending: Labor confronts Rinehart-led push to cut public service.

A pitched battle, egged on by Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart, is now under way over the efficiency of government. The Coalition is targeting what it calls wasteful spending on public servants in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis, while the government insists it is running a leaner – by $4 billion – and less mean bureaucracy.

It’s an Australian version of what Elon Musk intends to do to America’s public services. The opposition is now agitating for a “department of government efficiency”, a copy of the agency Musk is to head in Washington. Our DGE’s first task would be to sack 36 000 public servants (conveniently forgetting that when in office the Coalition cut funds for the National Audit Office).

Barlow’s article is largely about the consequences of cuts on service delivery – pension payments, NDIS assessments, issuing passports and hundreds of other services – and on the waste when, in the name of “efficiency”, public servants are replaced with much more highly-paid consultants. The current government’s policy of hiring more public servants to bring services back in-house has already saved billions in administrative expenses, and that’s before considering the economic value of advice given by public servants rather than by those with commercial interests. Barlow points to criticism that the current government has not gone far enough in restoring the public service.

On a similar theme you can hear Mike Seccombe on the Schwartz Media’s 7am podcast How Gina Rinehart's friendship with Trump will change Australia. He describes that close relationship, and her generous donations to the Coalition parties. She has cultivated close relationships with Coalition members, particularly those opposed to action on climate change.

Dutton’s acceptance of her offer of her private plane for his trip to Bali may have saved taxpayers a few thousand dollars in airfares, but the implied debt in terms of reciprocating the favour could cost Australia billions. He has been repeating, virtually word-for-word, Rinehart’s policy lines – her gross overstatement of the mining sector’s contribution to the Australian economy and public revenue, her advocacy for nuclear power, and her Trumpian assertions about immigration.

Seccombe goes on to describe the international coordination of hard-right pressure groups – the Atlas Society internationally and its Australian offshoots. Rinehart is closely involved in that coordination, which is probably why she was at Mar-a-Lago on election night, hobnobbing with Nigel Farage and Elon Musk.

A reform wish-list – without losers

A challenge for economists. Put the case for a list of economic reforms – at least 20 – that would meet a trifecta of macroeconomic benefits – higher GDP, lower inflation, and more government revenue. Bonus marks will be allocated if the proposals contribute to better health and a reduction in emissions.

That’s the task the government set the Productivity Commission, when it asked it to assess a set of reforms proposed by Commonwealth, state and territory governments, mainly in the context of a review of competition policy. It reported last month: National Competition Policy Analysis.

Some of the most productive reforms included removing or streamlining occupational licensing requirements and reviewing regulations in the construction industry to allow for greater productivity. The Commission also used the occasion as an opportunity to call for adopting measures recommended in its 2018 report on competition in the Australian financial system.

The reforms are mainly about lowering barriers to entry to industries, and removing or revising regulations with adverse consequences, the cost of which exceed the value of their benefits.

The Commission hasn’t looked at cases where changes that broke up natural monopolies in the name of competition, or contained the size of government, have had adverse consequences for efficiency, inflation and distribution. These include the National Electricity Market, toll roads, support for private health insurance, and privatization of the Commonwealth Bank.

Investing in our public broadcaster

ABC Chair Kim Williams in his recent National Press Club Address made a plea for investment in the ABC. At a time when commercial media, particularly high-quality commercial media, are struggling, the ABC is taking more of the load of providing objective, trusted news analysis and commentary, but with a shrinking budgetary allocation.

He provides some hard figures on financing: in the last decade the ABC’s operating revenue from the Commonwealth has fallen by 14 percent; over the last twenty years the ABC’s share of Commonwealth outlays has fallen from 0.31 percent to 0.13 percent; Australia invests around 40 percent less per person in public broadcasting than the average for a comparable set of 20 OECD democracies.

His speech is more than a pre-budget bid. It is a case for investment in our security – the security of having a trusted source of news and information in a world awash with misinformation and disinformation. And it’s a bid for investing in our own cultural capital – our stories, Australian stories.

He reminds us that with so many channels of news, propaganda, fake news, fantasy, outpourings of anger, disinformation and misinformation available at the touch of a screen, media literacy is the front line of that security. (Economists will see the link to George Akerlof’s market for lemons: in a market where no one can judge the quality of what’s on offer, quality falls to the lowest standard.)

In light of the dangerously low standard of the political debate around the Voice and immigration, exploiting ignorance of our democratic institutions, Williams’ comments are apt:

More ambition too is required to refresh popular understanding of Australia's great national institutions — our parliaments, our courts, our regulators and public policy processes. And of course, the security offered by the world's best electoral system. Australians simply don't realise how good our democratic institutions are. Informing them about this would be the most direct expression imaginable of the ABC as a proud servant of our democracy and our freedoms.

Most importantly, he wants to see more young people among the ABC’s audience. It’s not a pitch for ratings: rather it’s about giving them the resilience to enjoy “a better future” in which they can navigate a media landscape that’s going to become tougher over their lives.

There is a transcript of his speech on the ABC website. The full 64-minute session is on YouTube. Q&A starts at 33 minutes. At least two questions are from sources hostile to the ABC. To those questions Williams gives a straight defence of the truth as a standard: he is not to be swayed by the postmodernist view that all opinions are of equal standing. Two questions relate to right-wing rabblerouser Joe Rogan. Williams’ assessment that Rogan preys on people’s fear, vulnerabilities and anxieties, and his personal view that he finds Rogan’s behaviour “deeply repulsive”, seems to have upset Elon Musk.

One questioner reminded Williams that Gina Rinehart, Peter Dutton’s close friend and confidant, has called for the ABC to be privatized.

Private health insurance – a channel for the young to subsidize the wealthy old

“Young people flocking to health insurance despite cost-of-living crisis” was the headline in a press release by Private Healthcare Australia. The ABC jumped on the bandwagon with a post Mental health, endometriosis treatment behind a spike in young people taking up private health insurance, and a TV news item Australians under 30 driving growth in private health insurance.

The excitement has been driven by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority releasing its latest quarterly private health insurance statistics, covering the September quarter 2024.

Strange, is it not, that a supposed “cost of living crisis” should drive young people to buy a product they don’t really need? The whole set of subsidies for private health insurance is directed at pressuring fit and healthy young people into subsidizing PHI for those over 65 – the securely-housed group least touched by inflation, many of whom are better off than they have ever been.

There is hype in Private Health Care’s claim that there is now a record 45 percent of the population with PHI hospital cover. It has risen from 44.8 percent to 45.0 percent in the last quarter, still well down from the 2015 peak of 47.4 percent.

A look at the figures shows that between September 2023 and September 2024 there has actually been no significant change in the number of people aged 25-34 taking out PHI – unless you call a rise of 428 individuals “significant”. But there has been a rise in the next age cohort down, 20-24, enrolled in PHI. This is probably explained by changes in regulation allowing students and dependents to stay on their parents’ health cover until they are 31 under the Extended Family Health Partners measure, a policy announced in the dying days of the Coalition government. It’s a good deal for the insurers, because people with children up to age 31 are generally net contributors to PHI, rather than net drawers from PHI.

Health Minister Mark Butler has criticized the previous Coalition government for its generosity to PHI. Last month he criticized a 1994 decision by then Health Minister Peter Dutton for freezing the Medicare Levy Surcharge in nominal terms (an income of $90 000 for a single person), thus pushing many more people into paying higher taxes or buying PHI that they didn’t need. The government has restored indexation but it has not made it retrospective: it is now $97 000, instead of around $120 000 had it been indexed since 2014.

Through housing and superannuation tax breaks young people are already being made to subsidize well-off older people. If concern for mental illness and endometriosis are really driving some people into PHI, the government should be funding these services through Medicare. It has made some promising moves on endometriosis, but has a long way to go on mental illness.

Fortunately, tax breaks and jawboning haven’t enticed many people into PHI. If the government were seriously committed to Medicare it would abolish all tax breaks and fund Medicare properly, supported by a rise in the Medicare Levy Surcharge.

Urban development – how does the government intend to make life better in Lakemba and Elizabeth?

Australia is a strange country – a country with a huge land area but with 18 million of its 27 million people packed into five big cities.

In times past governments pursued policies to redress this imbalance. The Whitlam government established the Department of Urban and Regional Development, but it had a short life, partly because its visionaries didn’t understand that new settlements needed associated transport infrastructure. Its lasting mark on the Australian landscape is a small open-plains zoo near Murray Bridge.

National Party ministers have had a passion for decentralization, but in policy terms that has often been realized in subsidizing dying industries to set up in National Party electorates. The National Party found, to its dismay, that establishing universities and other industries employing educated professionals in rural cities helped develop well-informed voters, who turned against their benefactors.

Now another Labor government is having another go at developing a National Urban Policy, which Jenny McAllister, Minister for Emergency Management and Cities quietly announced last week, while everyone else in government was running around trying to push legislation, including housing legislation, through the Senate.

The document should get top marks for presentation. Only a grouch would disagree with its “vision for sustainable urban growth”, endorsed by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments. It aims at:

Ensuring our cities and suburbs meet the needs of current and future generations, our governments commit to collaboratively govern and holistically plan our cities within existing footprints first and with housing affordability as a primary goal.

And it assures readers that:

We are planning metropolitan regions which are well-connected, foster active transport, drive innovation and support our cities and suburbs as hubs of productivity.

Writing in The Conversation – Cheaper housing and better transport? What you need to know about Australia’s new National Urban Policy – Ehsan Noroozinejad and Nicky Morrison of Western Sydney University summarize the document and they find nothing with which they disagree, but they ask if the policy can address challenges of providing housing, dealing with climate change, and promoting social inclusion. They use their review to provide a link to their own university’s practical ideas for funding infrastructure in outer metropolitan growth areas.

They conclude that the policy needs funding and commitment of resources if it is to achieve its goals.

The broader question, not addressed in this document, and only partially addressed by the Whitlam government, is whether we should have a geographical settlement policy, of which an urban policy would be a part. This document seems to consider urban growth almost as an exogenous variable, to which governments must respond. Their only hint of a broader settlement policy is that cities should remain within their existing footprints.

There are many lobbies for continuing urban growth. Businesses and government agencies reap the benefits of urban scale economies, but individuals and households bear the cost of urban scale diseconomies. There is possibly some optimum urban size, almost certainly less than Melbourne’s or Sydney’s 5 million, that maximizes the total returns to scale. Surely policymakers, aided by urban geographers, can come up with data on scale economies and diseconomies, rather than assuming ongoing urban growth is unavoidable.

The other omission in this document is any acknowledgement of geography as a contributing factor in urban development – how our landforms and climate have shaped our cities, and how climate change will bring pressure on particular regions, requiring de-population or expensive adaptation. The document mentions the challenges of climate change in general terms, but by now it should be possible to identify certain regions, such as the far western reaches of Sydney’s conurbation, that are particularly vulnerable.

As international reports come out, nominating Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide as the world’s most liveable cities, we tend to rest on our laurels, overlooking the realities of life in regions within these cities. If this document gets policymakers to start thinking clearly about regions, understanding that everyone in Australia, from Oyster Bay to Oodnadatta, lives in a “region”, the venture will have been worthwhile as a starting point.