Australia’s energy transition

Nuclear power – there are safety fears but the biggest danger is economic

Men and women have distinctly different views on nuclear energy.

There has been a great deal of media cover about a survey commissioned by the Australian Conservation Foundation showing that by a wide margin women are much more wary than men about nuclear energy. In response to the statement “Nuclear power would be good for Australia”, 51 percent of men agree, 26 percent of women agree. A gender divide had been found in earlier surveys but this is particularly large.

Further questions in the survey strongly suggest that people’s main concerns are about the safety of nuclear power.

On the economics of nuclear power 47 percent of men and women agree that renewables will deliver cheaper energy than nuclear. Of the other 53 percent, the results are mixed: 31 percent of men disagree, and older men and women are more likely to disagree than younger men and women.

The Parliamentary inquiry into nuclear energy has been in the Latrobe Valley, the location of Victoria’s ageing brown coal power stations, hearing people’s views about nuclear energy. Views are mixed, but people do not seem to be particularly informed. You can hear Patricia Karvelas on Radio National interviewing National MP for Gippsland, Darren Chester, giving his views and passing on what he is hearing from voters.

Chester seems to be more open-minded than most of his Coalition colleagues, but is clear from the interview that there is a great deal of confusion and ignorance about nuclear energy. Among misunderstandings, some based on a lack of information, some based on deliberately circulated lies, are:

Safety. Spectacular accidents – Fukushima, Chernobyl, Three Mile Island – have given nuclear power a bad press. But nuclear power plants have a good safety record: that’s one reason they’re so expensive. There are real concerns about the storage of nuclear waste, but these don’t seem to be coming up in public consultations.

The supposed need for base-load power. Even more than coal-fired plants, nuclear power plants fit into a traditional “base load” power model. Their marginal cost of operation is zero, while their fixed costs are huge. To make economic sense they therefore have to run at full power 24/7. A power system based on wind and solar, however, needs to be firmed with dispatchable power when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. Until there is enough capacity in batteries and pumped hydro, peaking gas plants will serve this purpose, but “base load” power, whatever its source, does not fit into a renewable system.

The supposed $500 billion understatement of the cost of the Integrated Systems Plan. This figure, quoted by Chester, is based on an outright accounting falsification.[1] There is also the claim that the cost of constructing transmission lines required under the ISP could blow out. Underestimation of costs is a common problem, but it likely to be far more significant with nuclear reactors, particularly untried modular reactors, than with building steel towers, a very old technology.

In any event the ISP probably overstates the required amount of transmission capacity required. The tumbling cost of batteries, and the uptake of electric vehicles, combine to make more firming capacity available on a distributed basis, negating some of the need for transmission capacity from renewable hotspots.

The environmental costs of renewables. There are aesthetic considerations around the appearance of transmission lines and wind farms, and concerns that native forest may have to be cleared to build transmission lines. These are genuine but surmountable problems: our agricultural landscape is already badly scarred. But for the most part there has been a beat-up around these issues, such as ridiculous claims that to supply enough power, solar panels will displace a large proportion of our food-growing land, that animals cannot graze near wind farms, through to conspiracy theories about health effects from panels and windmills.

Geographical bewilderment. Many proponents of nuclear power point out that other “developed” countries have nuclear power and that Australia is the odd country out. Australia is also the odd country out in terms of its geography. Comparisons with Europe and Canada are meaningless. Melbourne is on the same absolute latitude as Athens. The southern tip of Tasmania is at 44 degrees while the Canada-US border is defined by the 49th parallel. (The unconvinced can look at this flipped map.) Those countries depend on nuclear power because of their latitude.

The ACF adds to our understanding of the politics of nuclear power, confirming that many people are afraid of it, but there is a risk that the Coalition will want to keep a focus on risk, because it is easy to find experts who can quell those fears, and it is easy to label nuclear’s opponents as soft-left tree huggers. That would conveniently distract the electorate from the economics of nuclear power in Australia (it is absurdly expensive) and from its environmental cost (it would require many years’ extension of fossil fuel plants).

1. Assessment of investment projects uses an established technique, “discounted cash flow analysis”, to account for the time cost of expenditure and revenue. The $500 billion arises from a deceitful comparison of a properly discounted analysis with an undiscounted figure. See the November 23 roundup: “The Coalition’s nuclear campaign – fool the public with bad mathematics” . ↩

Dealing with peak demand – load shedding

Some of the most disappointed people in Australia must be those in the right-wing commentariat who predicted that as a heatwave spread across southeast Australia last week there would be blackouts because of Labor’s reckless push to renewable energy.

“In the end, the only blackouts were in the media headlines” was how Giles Parkinson of Renew Economy described the outcome. In fact, due to good management, although the peak load was high – 13 000 MW in late afternoon – New South Wales scraped through with help from demand-management measures, as clients were paid not to use power they didn’t need. (Peak demand in New South Wales is normally around 10 000 MW.)

But the grid, reliant on unreliable old gas and coal generators, is fragile, and it is taking time for wind, solar and storage projects to come on stream. (There is a huge amount of solar, wind and battery storage capacity on the drawing boards and in the pipeline.) Parkinson has another post about the way market rules need to be changed to speed up the provision of new capacity, including payments for investors in standby capacity which may seldom be called on. Not fit for purpose: Australia’s energy market rules to be rewritten to keep pace with renewables.

Building new capacity is all on the supply side, but Parkinson’s point is that more can be done on the demand side, scaling up the measures used during that heatwave, particularly through extending them into domestic situations. Water heaters that turn off for a time, washing machines that can be paused mid-cycle, air conditioners that can be turned up a degree or two: these are all ways of reducing load with almost no inconvenience to customers. A combination of commercial and domestic load shedding can reduce peak demand by around ten percent. In any market it’s almost always the last few units of demand that are most expensive to provide (remember those funny curves in Economics 1).

Technically all that’s required are smart internet-connected appliances, and these are available off the shelf, but markets have to be developed and customers have to be educated.

And politicians have to change their thinking, because the Coalition is still locked into its idea of “base load” and a one-way relationship between big coal or nuclear power stations and passive consumers.

Our annual emissions report card – we’ve slipped a bit but we can get back on track to our 2030 target

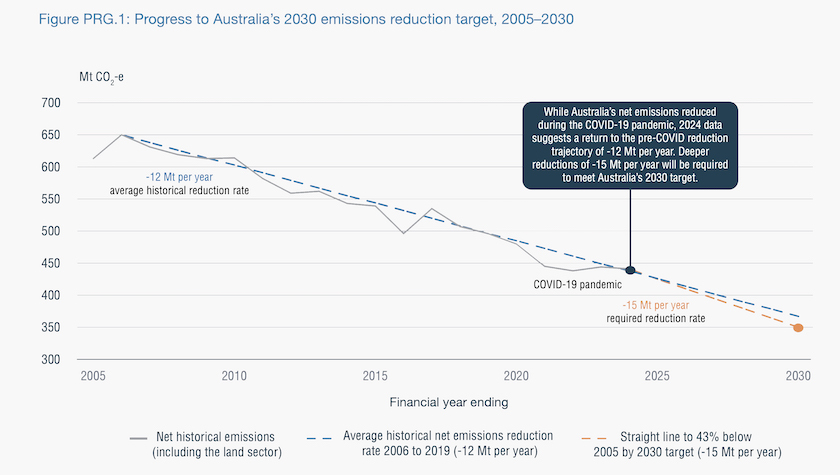

Our emissions need to fall faster if we are to meet our 2030 target of 43 percent below 2005 levels.

That’s the message from the Climate Change Authority’s 2024 Annual Progress Report.

Its findings are summarized on an annotated graph, reproduced below. Our path is along the blue line: to get back on track we have to move to the orange line.

The report covers all sectors, including agriculture and transport. The recommendations on this year’s report prioritize electricity which is responsible for about a third of emissions and with a target of an 82 percent emissions reduction. It calls for “firmer and longer-term foundations for the Capacity Investment Scheme”, and use of distributed commercial and household resources for generating and firming electricity supply.

Those relate to the supply side: we also need to improve our building efficiency standards: our buildings have some of the world’s poorest energy efficiency standards. Achieving efficiency on the demand side has high returns, not only in reducing the need for generating capacity, but also in reducing the need for transmission capacity.

In relation to other sectors it notes that emission reductions under the Safeguard Mechanism, applying to large industrial facilities, seem to be on track, but that’s based on the short time it has been operating under present rules. Reducing emissions from transport will depend on the effectiveness of the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, due to come into effect next month. That standard concerns cars; there needs to be more attention to trucks which account for 23 percent of transport emissions.

One of the report’s recommendations is a “major focus on removing barriers to the deployment of clean energy infrastructure”. There are several barriers, but one that has come to prominence is farmers’ objection to construction of wind farms, solar farms and transmission lines.

Much of that objection seems to have been a beat-up by the National Party and their backers in the fossil fuel industry. Farmers are indeed concerned about competing priorities and compensation for land use, and some have concerns about aesthetic issues, but according to research by Farmers for Climate Action, conducted among people living in climate shift regions, there is strong support (70 percent) for energy projects on farmland. Only a minority (17 percent) are opposed. Probably because of disinformation campaigns, however, only 30 percent of farmers in Renewable Energy Zones realize that they can make good money from clean energy if they deal with clean energy companies to use their land.