Health

Where our health dollar goes

Through taxes, private health insurance and dipping into our own pockets, we spend about $10 000 a head on health care.

That figure may seem to be surprising, because most of us, most of our lives, have the good fortune to have little involvement with our health care system.

Every year the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare publishes a detailed matrix, cross-classifying sources of spending on health with the destinations of that expenditure – hospitals, pharmaceuticals and so on – in the publication Health expenditure Australia. It’s a great source of data for policy nerds addicted to spreadsheets, but it isn’t particularly user-friendly.

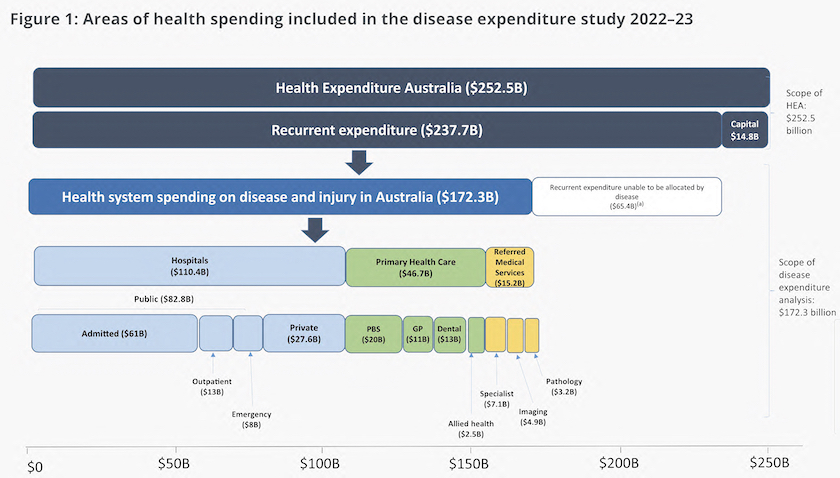

This year it has produced a report Health system spending on disease and injury in Australia presented as a set of web pages, many of which invite the reader to drill down into further detail. Anyone asking “where’s my $10 000 going” would find its main graphic informative, copied and reproduced below.

Most people’s experience is around primary health care – GPs, pharmaceuticals and dentists – the green boxes in the diagram. The lion’s share of expenditure, however, is on hospitals – the pale blue boxes.

One of the more informative graphics in this report contrasts spending by condition with the burden of disease. Spending on condition is measured in dollars – a complicated but straightforward calculation: it is possible to estimate with reasonable accuracy how much spending is directed to treating cancer, accidents, diabetes and so on.

The burden of disease is typically measured in terms of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). That is, a sufferer’s loss of comfort and amenity associated with that disease. In some areas, such as treating injury, the distribution of dollars and spending pretty well match. But in two disease categories, “mental health conditions and substance abuse disorders” and “respiratory diseases” the imbalance stands out strongly. If our allocation of spending related more closely to the burden of disease we would probably be spending more on these conditions – assuming extra spending can have greater effect.

For a general summary of the AIHW report you can listen to a 7-minute interview with Norman Swan on Radio National: What health spending tells us about access - Health with Dr Norman Swan. Contrary to some circulating panics, our spending on health care is under tight control and compares well with spending in other countries.

But evidence of people forgoing health care because of its cost suggests that we are failing to provide universally accessible health care. Data on those financial hurdles are in the most recent ABS publication on Patient Experiences, revealing that an increasing number of people, particularly younger people and people from disadvantaged regions, are delaying or refraining from using health services because of cost.

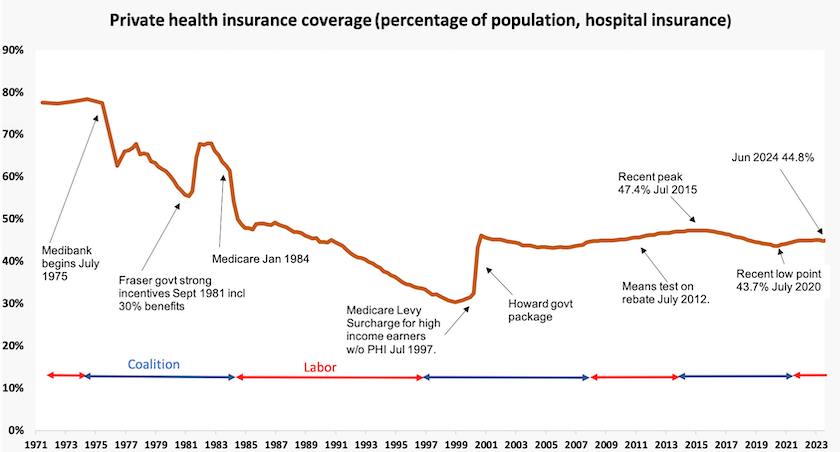

In this context it is informative to trace the long path of private insurance over the last half-century, since the Whitlam government introduced Medibank, the forerunner of Medicare, programs designed to provide universal access to health care, obviating the need for private health insurance. Over the 13 years of the Hawke-Keating government, private insurance dropped, but they didn’t succeed in its eradication. The Howard government rescued private insurance with a set of very expensive subsidies, maintained and modified by successive governments, Coalition and Labor.

Private insurance, because it attracts resources away from public hospitals, and because it lacks the means to control providers’ costs, remains an impediment to universalism. (That inability to control providers’ charges is illustrated in a current conflict between health insurers and private hospitals.) We would all be better off if private insurance were eradicated, and if we paid a little more tax to fund public and private hospitals through Medicare.

But the current government lacks the political courage of earlier Labor administrations: the Whitlam government took the nation to a double-dissolution election to establish Medibank. And we are still no closer to dental care being covered in Medicare.

Homelessness

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has pulled together data on the life expectancy of people who are homeless, confirming studies that on average people experiencing homelessness die an average of 22 to 33 years younger than those who are housed. The death rate for homeless men is much higher than the death rate for homeless women.

The AIHW’s web page is data rich, all with the same message – the homeless are dying younger and the number of homeless people suffering a shortened life is growing quickly. (That does not mean homelessness is necessarily a cause of early deaths, because those who are homeness usually have a number of adverse health conditions.)

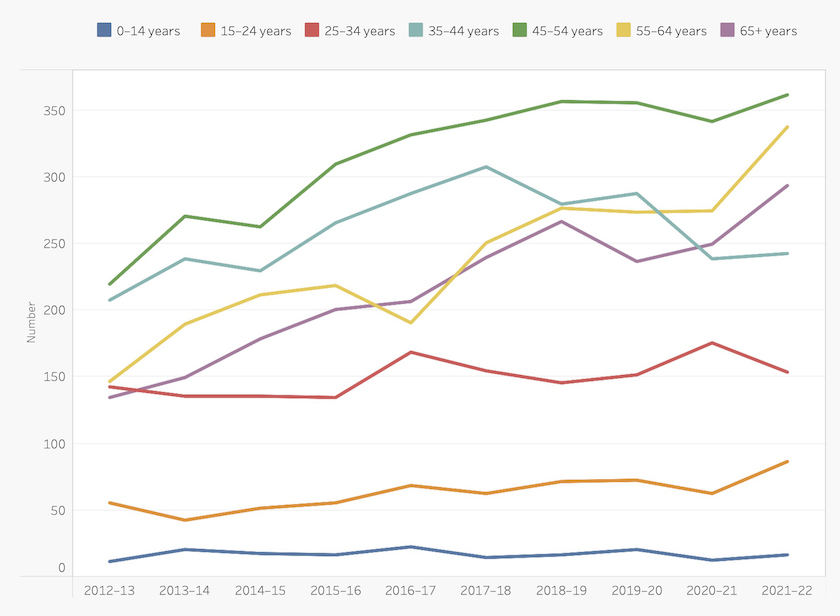

I have picked one of the AIHW’s many confronting graphs, this one showing the age distribution of hommeless people in their last year of life, to illustrate the message. It’s copied below.

People who received Specialist Homelessness Service support in the last year of life, by age

More on Covid-19

In the roundup of November 9 I linked to the government’s Covid-19 Response Inquiry Report.

At the same time Andrew Podger, former head of the Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, was finishing a Mandarin article: Health Department must listen to these lessons from our COVID-19 experience, outlining his own learning from our response to Covid 19, and reviewing the book Australia’s pandemic exceptionalism: how we crushed the curve but lost the race by economists Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden.

Podger points to lessons for policymakers – “the importance of speed of action in a pandemic, of gathering much more information to monitor the situation and to learn as a pandemic spreads, and of managing risks differently than in non-pandemic circumstances”.

He is critical of specific aspects of our Covid-19 response. For example he agrees with Hamilton and Holden that the Health Department was tardy in achieving vaccine coverage, thereby delaying a re-opening of the economy. But these criticisms are in the context of his observations of our extraordinary successes in dealing with the pandemic, particularly when we compare our response with the responses in other countries.

Most importantly there was enough good advice around, and enough politicians willing to listen to that good advice, to ensure that we didn’t go for a “let it rip” response, based on a belief that there is some trade-off between public health and economic objectives. This is particularly relevant when we realize that both the Commonwealth and New South Wales governments had centre-right governments at the time, which may have been ideologically predisposed against strong intervention. Such persuasion is possible only when there is a professional and trusted public service.

Unsurprisingly, as it turned out “the best economic advice was entirely consistent with the best health advice”.

Podger is particularly impressed by the way different agencies came together to ensure that people with expertise in economics and risk management worked with people with expertise in health program administration. Anyone familiar with Canberra’s bureaucratic rivalries would realise that this was a major achievement.

I confess to not having plodded through the 800-page government report, but my general impression is that Podger’s view is much more positive than that of the government’s authors. Where the government’s report saw political failures, Podger, with extensive administrative experience (he served as the Australian Public Service Commissioner for a time), saw the workings of a well-functioning public service, creative and capable of responding to extraordinary challenges.

The epidemiology of gambling

The government is does itself no favour in continuing to avoid legislating for a ban on sports betting. In Thursday’s frantic Parliamentary sitting it managed to ram through its bill on social media, where the evidence of harm is disputed, but it held over any action on sports betting, where the evidence is strong.

As the ABC’s Jake Evans points out, the government could pretty well be guaranteed support from the Greens and independents if they legislated for a ban. That would leave the Coalition, with its proposal to implement a partial ban, looking weak and indecisive, to use the words the Coalition is using to attack the government: Gambling ad ban delays prompt fury in parliament and contradictions among ministers.

The curse of online gambling was the topic of a seminar at Harvard’s Kennedy School earlier this month: At the seminar Harvard Professor Malcolm Sparrow drew on the work of The Lancet Public Health Commission on Gambling, which called on governments worldwide to treat gambling as a public health issue, just as they do for other addictive and health-harming commodities. Gambling has become so easy, he stated:

So rather than have to go to a casino, have to go to a bookmakers, wander into the corner store to buy your weekly lottery ticket- which is the way things used to be- the casino is now available on your smartphone and it’s in your pocket and it’s available 24 hours a day. It’s available seven days a week, without those kinds of natural impediments to engage.

Sparrow’s main concern is that because the Internet has made gambling so easy, it has become normalized as an everyday activity, rather than something confined to particular occasions and venues, such as Saturday at the races. He is also concerned that the gaming companies are exploiting not only poor people in rich countries, but that they are now targeting poor people worldwide.

He outlined the individual and social costs of unrestricted gambling, and cited evidence of measures that work. Mandatory pre-commitment is the most effective – more effective than bet-size limitation.

Nothing we don’t know, perhaps. In fact Sparrow cited Australian research in his assessment of the harm caused by unrestricted gambling. We don’t have any excuses for our inaction.

Political affiliation and health

In the US life expectancy for people living in Democratic-voting states is more than two years longer than for people living in Republican-voting states.

That’s one of the findings Lesley Russell, of the University of Sydney, refers to in her Conversationcontribution: In the US, political division can take a significant toll on people’s health. Australia should pay attention.

The quest to find the social determinants of health is difficult territory for researchers. People’s political orientation is closely related to education, and people with low levels of education tend to vote for parties on the right.

They also have poorer health. Finding the independent variables that may reveal some causal relationship between political affiliation and health, rather than simply a correlation, is difficult. But Russell has apparently found some causal relationships: political polarization seems to be bad for people’s health. This is essentially the other side of research that finds that social cohesion and public trust are conducive to good health.