Politics

George Megalogenis on the coming election campaign

George Megalogenis’s Quarterly Essay – Minority report: the new shape of Australian politics – is a hard-nosed analysis of federal politics, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data, leading to his predictions about the possible outcome of next year’s election.

There is a small possibility that Labor will once again form a majority government. But there is usually a swing against a newly elected government, Labor or Coalition. When governments change there is inevitably some letdown in voters’ expectations – the expectations that led them to change their vote. Labor holds only a two-seat majority in the House of Representatives.

The prospect that the Coalition can form a majority government is even weaker. They would have to take 21 seats, some off Labor and some off independents, almost all of whose electorates are in our capital cities.

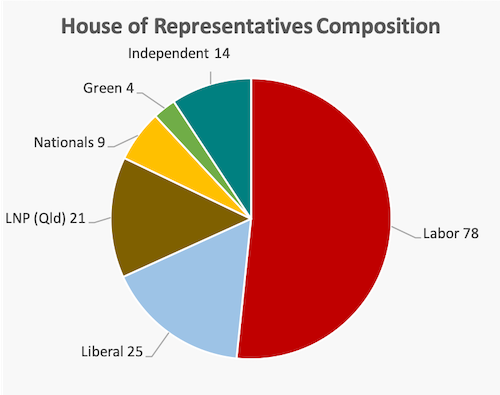

Reinforcing Megalogenis’s point, below is the graph, presented a couple of roundups back, showing the present composition of the House of Representatives. The Liberals are now the minor party in the Coalition. It’s all very well for the Coalition to have a solid base in Queensland (our most decentralized state) and in country regions, but most Australians live in the capital cities.

There have been landslide election outcomes before, but (contrary to the impression presented by partisan and lazy media), Labor is travelling reasonably well in the polls. People may be grumpy but they’re not in revolt.

The greater problem for the Coalition is the challenge of crafting a message that will resonate in the suburbs and in inner urban seats, lost to independents and the Greens. Megalogenis goes into fine regional detail about the outer suburbs where the Coalition would like to pick up seats.

They are not the homes of the old, disaffected working class – a demographic the Coalition has been winning off Labor. Rather, they are the regions that house multicultural Australia. While many immigrant groups are socially conservative, Dutton’s hard lines on immigration, on China, and on Gaza don’t resonate in these electorates. The Coalition’s hostility to learning probably doesn’t go down with immigrants hoping to give their kids a chance in a new land.

Megalogenis summarises the reason he believes both the old parties have little hope of forming majority government:

… the major parties have found themselves on opposite sides of the fault-line between New and Old Australia and between city and country. Neither has the language at the moment to build a bridge between the two – a bridge that would, incidentally, secure stable, majority government for the first party that inspires both constituencies.

There are too many possible outcomes for him to forecast the likely composition of a minority government, but he cannot imagine Dutton “fresh off a Trumpian campaign for nuclear power, lower immigration and a ban on refugees from Gaza” presenting his case for minority government to the members who will hold the balance of power.

That probably rules out a Coalition minority government. It does not rule out a de-facto Labor-Coalition coalition. In that scenario labor continues to hold government because the Coalition cannot muster the numbers for a vote of no confidence, but it negotiates all important legislation in “bipartisan” deals with the Coalition, freezing out the so-called “crossbench”. (Like “hung parliament”, the words “bipartisan” and “crossbench” belong to a political world that has been fading way for 80 years – the “Westminster” two-party world.)

In some ways that would be an extension of what the Albanese government is already doing in relation to policies around establishing an integrity commission, aged care reform, undocumented immigration and electoral reform. It’s probably the worst of all possible outcomes, because it entrenches the duopoly of the two tired old parties, muzzling the representatives of our creative and energetic inner-city regions.

Dutton’s little helpers

In the essay Megalogenis seems to overstate the political power of the Greens, who he correctly sees as more obstructionist than the independents. That probably has to do with the timing of the writing of the essay. It hit the streets just a few days before the Greens, reeling from poor electoral outcomes, and realizing that they were coming to be seen as forming an alliance with the Coalition to defeat Labor, sensibly decided to allow the government’s housing bill and other legislation to pass. You can hear him on Late Night Live – George Megalogenis on what a Labor minority government might look like – a few hours after the Greens announced their decision on housing – an issue Megalogenis identifies as of utmost importance in the coming election.

While his Late Night Live session provides a summary of his work, it only touches on the material covered in his essay, which includes a careful analysis of the politics of the Voice referendum, insights into the characters of Dutton and Albanese, and a description of the rich and complex political life of suburban Australia.

He explains a great deal about the workings of the Albanese government, including the reasons “Labor has blocked itself into the corner of incrementalism”. He writes about the government’s political failures, some resulting from its own misjudgement, some resulting from Dutton’s savagery, and some resulting from the Greens’ childish behaviour. His analysis puts some flesh on Laura Tingle’s post on the ABC about the government finding itself outgunned by a man with simple and angry messages.

Dutton’s strategies aren’t leading his party to an election victory, however.

Demography is not on Dutton’s side. Sydney holds two-thirds of the population of New South Wales and Melbourne, and Perth and Adelaide are approaching 80 per cent of their respective state populations. Only Queensland and Tasmania have a majority of the people still living outside the capital. The Liberals cannot afford to treat the teal electorates as an anomaly of inner-city wokeness that can be ignored in pursuit of a new mythical middle in the outer suburbs. The political center has been moving towards the CBD, not away from it, and to voters who are being denied the Menzies dream of home ownership.

Bipartisan bastardry

It’s no revelation to point out that politicians manipulate legislation and conventions to keep themselves in power. But it comes as a shock when they freely admit to such behaviour, as Minister Don Farrell did last week, when he explained the workings of changes to election funding. As Jason Koutsoukis reports in the Saturday Paper, when a group from Climate 200 approached him to complain that his changes would entrench the two-party system and lock out challengers, his response was brutally honest: “That’s the fucking point”.

His only semblance of a defence was to assert that “that’s how the Westminster system works”, as if it’s written into our Constitution (it isn’t).

Koutsoukis’ article goes on to explain the workings of the government’s proposals, covering much the same ground as was in last week’s roundup.

The ABC’s Tom Crowley has had a look at the proposals to see who would have benefited and who would have lost had they been in operation at the 2022 election: A re-run of the 2022 election reveals how Labor's new funding rules really work.

At first sight they seem to rein in spending by the big parties, but that’s before carve-outs are considered, such as “affiliation fees” paid by unions, getting around the caps of $20 000 per donor. Political parties would be free to reallocate spending caps of $800 000 per seat by shifting spending from safe to marginal seats, an option unavailable to independents.

The most severely disadvantaged would be Climate 200, subject to a paltry limit of $600 000, and new independent candidates without the access to public funding allowed to incumbents.

It now appears that the Coalition has pulled out of the deal, because they fear the $1000 cap on undisclosed donations will disadvantage small businesses and individuals who don’t want to be identified. In relation to individuals the Coalition’s concern, if not justified, is understandable – who wants to be identified as a donor to a party devoid of moral principles that is openly hostile to the public interest? As for small business, if small business has enough profit to be able to give generously to political parties they should be subject to an ACCC investigation.

The Coalition’s withdrawal should give the government a chance to re-think its reforms, and to negotiate an arrangement with those who will probably have the power to decide who will hold office in six months’ time.

Surprises in an opinion poll

William Bowe has drawn our attention to a DemosAU opinion poll on voting intention, conducted over 18-21 November.

The headline figures are hardly surprising. Primary support for Labor is 32 percent, less than 1 percent down from the 2022 election, and Coalition support is 38 percent, 2 percent up on the election, while the Green vote is unchanged. In line with other polls it has the two main parties on a 50:50 two party preferred terms.

It is in the demographic breakdowns that some surprising figures emerge.

The Coalition’s support follows an established age gradient – 24 percent among voters aged 18-24, 40 percent among voters aged 35-54, and 43 percent among voters aged 55+. But Labor’s primary vote is weakest in the 35-54 age band. Among voters aged 18-34, the group with the worst housing prospects, the Labor plus Green vote is 56 percent (34 percent Labor, 22 percent Green).

Similarly the Labor vote and the Labor plus Green vote is strongest among renters (who probably overlap with the 18-34 age group).

Housing is certainly an issue among the young, but they don’t seem to be turned on by what the Coalition may be offering.

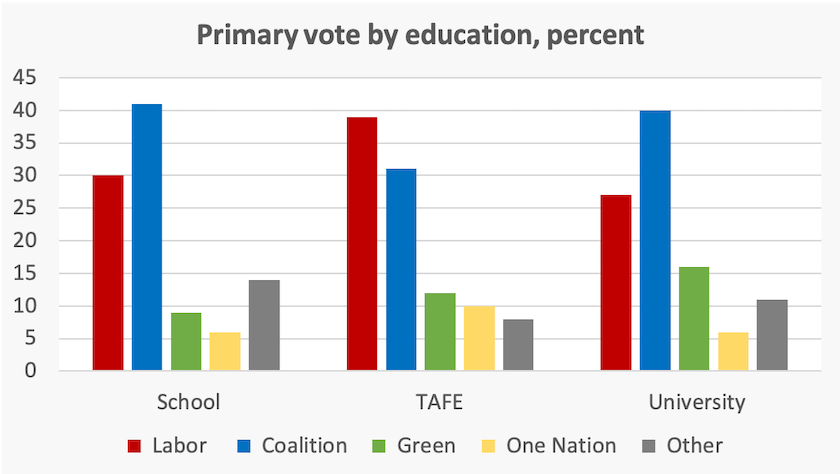

The poll also surveys respondents by their education attainment – “School”, “TAFE”. “University”. Labor support is highest among those with TAFE education, and weakest among those with university education. This is not in line with the finding from the 2019 and 2022 elections that saw Labor support strongest among university graduates, or with stories about tradies throwing their weight behind the Coalition.

The website gives further breakdowns by party – Green, One Nation and Other. The results according to education attainment are shown below.

Care should be taken in interpreting these smaller categories, because the total sample is only 1038, and by the rules of mathematics the sampling error is highest among small categories.

Why the legislative rush? Maybe it’s driven by the media’s metrics

The most extraordinary legislative rush has been for the social media ban, as if our children are all destined to a life of moral depravity if any time is wasted in passing the legislation.

The legislation passed in Thursday night’s extended Senate sitting, but many MPs were dissatisfied. It was as if opportunists in both the old parties colluded to wedge the bill’s opponents in their own parties and among independents and in other parties. Bridget Archer and Richard Colbeck – two of the few responsible adults on the Coalition’s ranks – had threatened to break ranks with their Coalition colleagues and vote against the ban, because it was unnecessarily rushed.

The same rush applied to a raft of other legislation.

The obvious reason for the government’s rush is that the government is planning an early election.

That’s too simple an explanation, however.

The Guardian’s Karen Middleton suggests the reason is that the government wants a story to take to the electorate – a story of activity and control: Hasty decisions and backroom deals betray Labor’s dire need for a decent story. It wants to counter the idea that it is weak and indecisive, a line Dutton is pushing.

Pressure to pass legislation is also coming from the media, because of a systemic bias in the media and in some academic circles. It’s the tendency to assess the performance of governments on the basis of their success or failure in passing legislation through parliament. It’s a neat “objective” metric, easily measured, and it relieves journalists and academics of the burden of making any normative judgement. The Howard administration scored well on that metric, which conveniently avoids assessing its trail of economic damage. Putin would probably be the world champion, based on his success in seeing his proposals get through the Duma.

Our political system is one in which it is rare, and is becoming even rarer, for the government to have a Senate that will wave through legislation. A reformist government, even a cautious reformist government like the Albanese government, will always find it difficult to get legislation through Parliament.

Most often Senate scrutiny is a healthy process, because the Senate has more voices than those of the two big parties, but sometimes it results from political grandstanding.

Our media commentators would serve us far better if they explained the reasons why the Senate blocks legislation, rather than issuing silly statements about the government’s legislative performance, as if the Greens’ posturing reflects poorly on the government.

We should be on the lookout for media biases. Partisan biases, particularly those of the Murdoch media, are usually glaringly obvious. It’s the biases from non-aligned media we often overlook. This obsession with legislative success is one such bias. Another, particularly relevant in the ABC, is the frequent reference to the present government not as “the government”, but to “the Labor government”, or simply “Labor”, as if it is not quite a legitimate government, but simply a stand-in during interregnums while we are waiting for the proper government to return. When the Coalition is in office it’s simply “the government”, never requiring a qualifying adjective. ABC journalists need to watch their language a little more closely.