Tax reform

Allegra Spender’s Green Paper

We rely too heavily on young people of working age to pay taxes for the whole nation.

That’s the main message in Allegra Spender’s Tax Green Paper, which you can download from her website: Economic reform that delivers for future generations. You can also hear her discuss her tax ideas with Patricia Karvelas on Radio National: Allegra Spender renews push for income tax changes. (That’s not a particularly informative headline for the 11-minute session).

In her paper, in her interview, and in interviews she gave last year (linked on her site), she expresses two broad concerns – the disproportionate burden placed on young people, and the allocative inefficiency of some of our taxes which impede productivity growth. These two concerns are in two early paragraphs in her paper:

Our tax system places undue burdens on the earned income of labour which is the major source of income and wealth for young Australians. It places barriers on home ownership. And without reform, the burden on labour income is only going to worsen, through bracket creep, an ageing population and the relative degradation of other sources of tax revenue.

Alongside intergenerational inequality we have lagging productivity and economic growth. Productivity growth is the only long-term source of real wage growth and cheaper prices. But we are not investing sufficiently in capital growth, nor forming and growing our innovative companies to the extent we need to. Once again, our tax system contributes to this.

Her green paper is rich in details exposing inequities and inefficiencies in our taxes. This analysis is mainly about Commonwealth taxes but there is mention of state and local taxes including payroll taxes, land tax and rates. She holds back on specific recommendations, other than suggesting that the Commonwealth establish a Tax Reform Commission.

Rather, it is about principles of tax reform. These include the usual textbook principles – efficiency, fairness, simplicity and adequacy. (There are a couple of others in the textbooks, but she covers the main ones.) Then she lists principles relating to the path tax reform should take. Besides lifting the burden on young people and improving productivity, she suggests that taxes be rebalanced to favour home ownership over investment in existing dwellings, that the revenue base should remain stable as demographics and consumption patterns change, and that tax settings should be adjusted to support our energy transition.

Those are the general principles. There is enough data in her paper that speaks for itself about the need for specific reforms. For example there is a chart showing that Australians have a lot more in investment property than all but two other OECD countries (both of which are tax havens). Another shows that for any given level of income, Australians over 65 pay much less tax than under 65s.

But she refuses to be drawn into the practice, driven by journalists and fear-mongering populist politicians, of ruling changes in or out. As she said in a 2023 interview (linked on her site), the two main parties have wedged themselves into stalling tax reform: she is determined not to be wedged. Even so, some journalists just don’t get it – you can hear on the same interview David Speers trying to draw her to make specific recommendations. But she understands the politics of tax reform: her paper has a section “tax and politics” which outlines the political leadership involved n tax reform.

If Spender’s ideas seem familiar, it’s because they are similar in many aspects to those Ken Henry raised in 2010. She acknowledges Ken Henry’s influence, and acknowledges, as Henry found, that the political environment is tough:

In this unfavourable political environment, tax reform will depend on engaging the community so that people understand the problem, why tax reform needs to be part of the solution, and the broad shape of that reform. I believe that members of the crossbench, more closely connected to the electorate and with higher levels of trust, could have a crucial role in building momentum for tax reform.

The Australian Council of Social Services has responded positively to her ideas., while suggesting that the reform agenda go further, “to lift overall public revenue to properly fund the services and income supports we need”.

In her interviews Spender stresses that the Green Paper assumes revenue neutrality, but that our taxes should change as demographics and consumption patterns change. Apart from some observations on excise, she goes no further, but any scholar looking at demographics and technology-driven consumption patterns realizes that just to retain our present proportions of public and private economic activity we need to collect more taxes (the Baumol principle). As a Member of Parliament representing Wentworth (between Sydney CBD and the Pacific, including some of the nation’s most expensive real-estate) she has to tread carefully around any implication that we need to collect more tax.

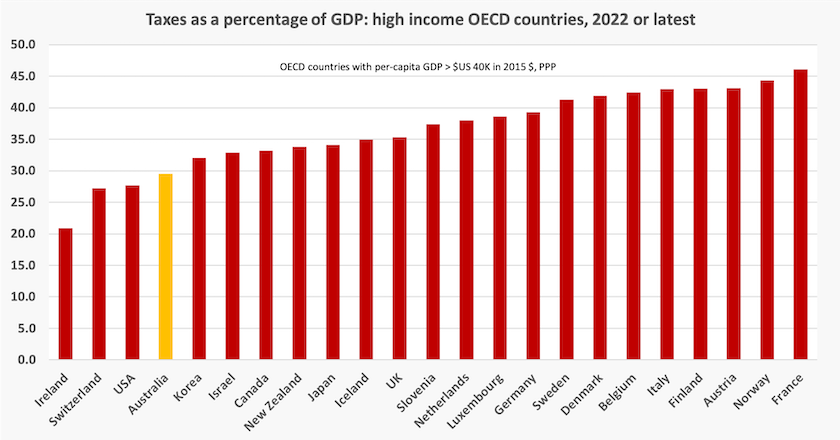

The reality is that Australia has almost the lowest taxes of all high-income OECD countries, as has often been pointed out in these roundups – re-presented in the graph below.

It is not only from well-heeled Teal voters she might encounter some pushback. There may be some resistance to her ideas from the left, because anyone reading her paper wound see a case for lowering our dependence on income tax and raising the GST.

On income tax her main point is that we have assigned the task of paying income tax to those in employment. Their burden could be lessened by lowering income tax rates, but extending normal income taxes to retirees living off superannuation incomes, while still maintaining the same proportion of income tax in the overall tax mix. (Many people point out, correctly, that income tax accounts for a large proportion of our taxes, but that’s only because we don’t collect much tax – as a proportion of GDP our income taxes are not far out of line with other countries.)

Nevertheless the left should think carefully about how it sees income and consumption taxes. Progressive income tax was a sure-fire way to keep the whole tax system progressive in a time of full employment and job security, but in an economic environment when people’s incomes change year-to-year, income tax may not serve that purpose so well.

The converse holds for consumption tax. Consumption taxes are generally regressive, but GST is one tax the plutocracy cannot avoid, and because our GST is directed to funding state government services, its net impact in contributing to the social wage is actually progressive.

That is not to suggest that the left should abandon its quest for progressivity. But they need to acknowledge, as Spender does, that demography and consumption patterns have changed. Wealth and transfer taxes (including inheritance transfers) may have to be part of the progressive tax mix. That’s another suggestion that may meet with a tad of resistance in Point Piper and Watson’s Bay.

Everything you wanted to know about Australia’s taxes and transfers

The Parliamentary Budget Office has released a paper Australia’s Tax Mix. It’s a data-rich presentation not only of Commonwealth taxes, but also of Commonwealth transfers and spending. Most of its time-series go back to the 1980s, some go back to the 1950s, and one goes back to Federation. It also has time-series on superannuation and some state taxes.

Its content is descriptive rather than normative, but it is clearly written for those with an interest in tax reform, and its data exposes some close-to-obvious cases where something has to change. It introduces itself with the statement:

This paper provides background information about how Australia’s taxes work, and about what it would mean to change the tax mix in a significant way.

Changing the tax mix is not easy, and this paper shows that only very large policies would significantly change the relative shares of taxes within the mix.

It would be an excellent resource for a graduate class in public finance, because it goes through the theory of taxation using Australia’s historical and current taxes to illustrate the theory and to expose situations where our taxes depart from those principles.

It describes some of the major historical reforms, including those of the Hawke-Keating era, and the Howard government’s replacement of the wholesale sales tax with the GST. The general message is that these reforms were effective at the time, but the whole system is constantly changing. For example GST, when introduced, brought in 4.1 percent of GDP as taxation revenue, to the benefit of the states, but that has fallen to 3.5 percent of GDP. Another source of Commonwealth revenue, tobacco and fuel excise, is projected to fall as people stop smoking and driving vehicles with internal combustion engines. There is no ideal “set and neglect” tax system: reform has to be an ongoing exercise.

The study includes an analysis of the efficiency of taxes. That is, the extent to which a tax distorts the pattern of economic activity that would occur in the absence of a tax. The less the distortion, the greater is the efficiency. It finds that over the longer term Commonwealth taxes have been becoming more efficient, while state taxes have been becoming less efficient.

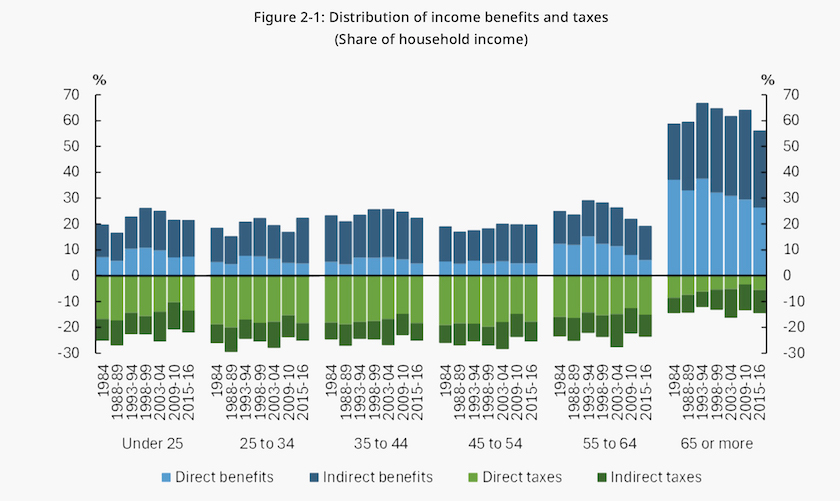

Its most informative section presents a picture of the way taxes, transfers and selected benefits affect different people by age, with data going back 40 years. The summary chart, copied from the report, is shown below. It’s a picture of who’s supporting whom in the tax and transfer system, presented in a way that needs no further explanation.

Others are conveying the same messages about generational injustices in our taxes. Appearing on the ABC’s The Business program, Aruna Sathanapally of the Grattan Institute explains how tax concessions for older Australians, particularly those aged 65 or more, are contributing to worsening intergenerational injustice. Millie Muroi, of the Sydney Morning Herald, explains the part played by housing tax concessions in widening the wealth gap between younger and older people. She acknowledges that at last the Treasurer is acknowledging the problem, even if our timid government lacks the gumption to tax older “self-managed” retirees in the same way as everyone else is taxed.

While the PBO avoids advocacy, it models two reforms that many tax experts have been advocating – doubling the GST while reducing income tax, and replacing all state taxes with a land tax. The latter would implement the long-advocated proposal by Henry George to collect more taxes on land. George’s ideas have been given renewed prominence as governments seek ways to tax wealth. Unsurprisingly the researchers find that both measures – increasing GST and collecting more land tax – would improve taxation efficiency.

The paper has a section on tax compliance, which includes an estimate of the “tax gap”. That is “the difference between taxes collected against the amount of taxes collected if all taxpayers were fully compliant”. The tax gap is a whopping $37.5 billion a year, or 7 percent of tax revenue. Most of the leakage is in the small business sector and in the shadow economy of criminal activity (they overlap), involving under-reporting of personal income.