Politics of the centre

On oligopoly

Coles and Woolworths, Qantas and Virgin – it’s all very comfortable. Compete at the margin, but don’t upset the ecosystem. Understand that your joint interests lie in keeping the system intact because neither of you may be able to adapt to a different ecosystem. Don’t worry if there are a few minor players – they save you from having to serve customers who don’t fit the model.

Oh, sorry, I stated writing notes for students about oligopolies, when I really intended to write about the government’s proposed electoral reforms.

Climate 200’s founder Simon Holmes à Court puts it better than I could. In a Radio National interview he slams political donation caps. (9 minutes)

The government’s proposed legislation is hard to follow, he explains, because it has so many exemptions and carve-outs, and complex definitions around what constitutes a political gift, for example. But basically it is designed to protect the interests of incumbents and the two established parties, and to raise the bar a little higher for aspiring independents. Writing in Pearls and Irritations – Faux electoral reform: entrenching the Australian party duopoly – Binoy Kampmark makes the same point.

Holmes à Court explains that the changes are not all negative. There is better transparency: the threshold for disclosure of a donor’s contribution is to be $1000, down from $16 900, and there is to be almost instant disclosure. He explains how the caps would work. The caps are also listed in an ABC post by Jacob Greber and Tom Crowley: Labor reveals plans for election funding overhaul with caps on donations and campaign spending. Holmes à Court is pleased that there will be a $600 000 cap per donor – a cap which could see Clive Palmer take a challenge to the High Court.

Joo-Cheong Tham of the University of Melbourne Law School, writing in The Conversation, notes that the reforms are ostensibly designed to reduce the influence of big money in politics, but he asks if rich donors will be the ultimate winners. He spells out details of the reforms, and goes on to draw attention to loopholes that can circumvent their stated intention to limit the influence of rich donors.

Independent Kate Chaney makes many of the same points as Simon Holmes à Court, on a Radio National interview: Independent raises alarm over political donations cap. Among her concerns is the generous $90 million cap on political parties, which can, de facto, supplement individual candidates’ campaigns. She is also annoyed by the process in developing the bill. She paraphrases the attitude: “we’re going to work it out with the Liberal Party and will let you know afterwards”. (You can read her draft bill on her website.)

In criticizing the process Chaney is in good company. According to a poll commissioned by The Australia Institute, 81 percent of people surveyed believe that major changes in electoral law should be reviewed by a multi-party committee.

You can hear the views of Kate Chaney, Monique Ryan, Helen Haines, and Senators David Pocock and Jacqui Lambie on the ABC 730 program: Independents blast Labor’s proposed overhaul of election donation laws. (But if you expect to meet them in the Qantas Chairman’s Lounge you’ll be disappointed – the crossbench independents have decided to eschew lounge membership and upgrades.)

So-called political realists may say it’s naïve to hope that the major parties could behave in any other way. But Labor doesn’t have to be bound by such a dismal political model. In its decision to negotiate only with the Coalition – as it had done with legislation on an independent corruption commission – it is sending the message that it lacks the courage to assert social-democratic principles.

If Labor is committed to reform, why should it compromise with a party with a terrible record on integrity and that has shown little respect for democratic institutions? And why does it treat with contempt parliamentarians who are on the side of reform?

The Centre must hold

On Radio National’s Saturday Extra last week, Kylie Morris interviewed Yair Zivan on the virtues of centrism: Is political centrism the answer to extremism and polarisation?.

Attention paid to the popularity of parties on the far right – most notably Trump’s success in America – distracts from cases where centrist parties and movements are succeeding.

Morris points out that we tend to over-estimate the degree to which political parties are polarized. It has been a long-standing tactic of parties on the right to portray parties on the left as dangerously radical.

In that regard we may recall that in past times Coalition politicians claimed that the Labor Party was under the control of communists. In current times the accusation is that Labor is obsessed with “woke” issues.

Zivan said that centrism, almost by definition, is hard to sell to the electorate. Political extremism gains attention in ways that centrism doesn’t. Centrism, however, can carry a strong message about good government. It is not some insipid set of political compromises – a little bit of socialism here, a little bit of market capitalism there. (That was the shortcoming of Blair’s “third way” – it had no consistent set of principles.)

Yair Zivan is editor of the book The centre must hold: why centrism is the answer to extremism and polarisation, a series of essays, including a contribution from Malcolm Turnbull.

Social cohesion and wellbeing: not all is well and it’s a long-term trend

It’s easy to pick up the vibes that Australia is in bad shape – our politics are too polarized and we are suffering a “cost of living crisis”.

But that’s not what the Scanlon Foundation Research Institute found in its 2024 review of social cohesion.

If you click on the site you have the choice of a 4-minute podcast of its main findings, an informative infographic, or the full 111-page report.

Migration is one issue of concern to Australians. Since 2022 there has been a marked increase in the proportion of respondents who believe we are taking in too many migrants. But it is hardly an outbreak of national xenophobia: while 49 percent of respondents believe the level is too high, this concern is balanced by 40 percent who believe it is about right, and 9 percent who believe it is too low. Also the belief that our level of migration is too high is concentrated among older people and Coalition supporters.

In fact, as in previous years, more than 90 percent of respondents believe immigrants make good citizens, and 85 percent of respondents believe that multiculturalism has been good for Australia. There isn’t much in these figures for the racist right, or for those in the Coalition who want to run a Trumpist line on immigration.

In the last year there has been a small uptick in negative attitudes towards Muslim and Jewish people: 33 percent of respondents report “somewhat negative” or “very negative” attitudes to Muslim people, and 13 percent of people report similar negative attitudes about Jewish people, but overall our attitude to both groups is neutral or positive. Negative attitudes to Muslim people are most pronounced among older people.

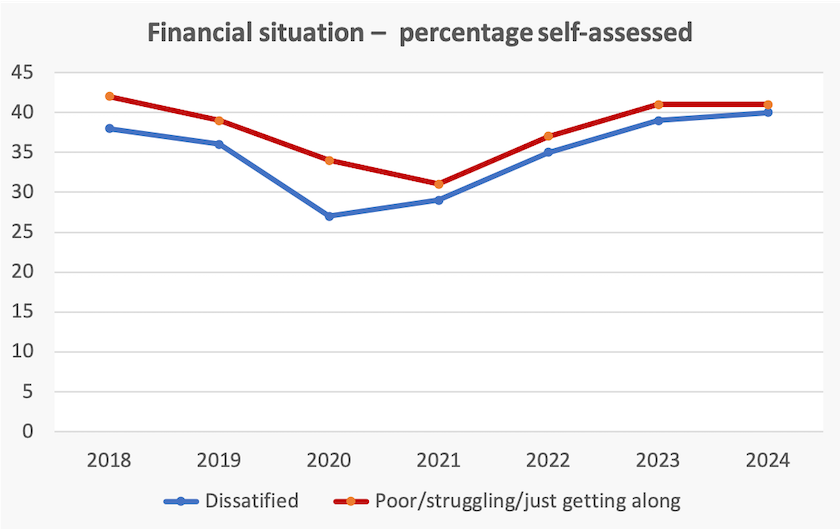

The survey asks a number of people about their financial situation. It’s clear that many Australians are struggling: renters and younger people are particularly likely to report financial stress.

But there is nothing in this data to suggest that in the last two years Australians have suddenly been overcome by a “cost of living crisis” – a notion that seems to seek to blame the Albanese government and the Reserve Bank for people’s financial stress.

The graph below is plotted directly from the Scanlon data, showing its two main indicators of financial stress. Our levels of financial stress have simply returned to pre-pandemic levels.

That is not to suggest there is no problem. Some figures in the survey are disturbing. For example 13 percent of respondents report that they have gone without meals because of financial stress. (John Hewson gives a detailed account of people’s food insecurity in a recent Saturday Paper article Why can’t so many Australians afford food?.)

Also inequity in access to housing is the source of much discontent, but it hasn’t arisen just in the last two years.

Our financial situation may be little changed but the Scanlon survey suggests that since 2017 there has been a decline in social cohesion and national pride, particularly since 2020. It finds an increasingly pessimistic mood among respondents, including an expectation that life in Australia will be worse in the next 3 to 4 years.

Another study released this month has been the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Report, a regular survey conducted by Australian Unity in partnership with Deakin University. Its findings are generally in line with those of the Scanlon report. Australians’ satisfaction with life, although high, has been on a downward trend over this century so far.

One striking finding relates to loneliness. Younger people are much more likely than older people to report that they are lonely: 45 percent of people aged 18 to 24 report being lonely. These findings align with the Scanlon findings that young people are less likely than older people to report that they enjoy a sense of belonging and a sense of worth.

The Australian Unity researchers speculate on causes for these feelings of loneliness: contributing factors may be the use of remote operations by universities and workplaces, and people’s use of social media as a default means of communication. Other findings and comments by social scientists are on an Open Forum post: All is not well in Australia.

Along broadly similar lines the Essential poll has been asking respondents since early 2022 whether our country is heading in the right direction or along the wrong track. Just after the Albanese government was elected there was a big improvement in our confidence about the direction the country was heading, but that didn’t last long: over the last year around half of respondents believe we are on the wrong track while only a third believe we are heading in the right direction.

The Scanlon survey asks about our trust in institutions. Traditional media score poorly and social media score even more poorly.

Notably respondents show a great deal of trust in the police, the health system and the education system, which are all primarily government services. But respondents show far less trust in government – state and federal. There’s a message here for politicians and senior public servants: people have more respect for the troops and NCOs than for the officers.