What Trump’s return means for Australian politics

Can a Trumpist approach to politics work in Australia?

“It’s the economy stupid” is the time-honoured refrain about US elections. Does the same hold here?

Interviewed on ABC Radio National, Kos Samaras certainly thinks the US election has warnings for our own government, particularly in a global environment where grumpy voters are throwing out incumbent governments and working-class voters are turning to populist right-wing parties: Did Democrats abandon working class voters?. (7 minutes)

With bewilderment and dismay, social-democrats point out that their policies are more friendly to the working class than those of right-wing populists – Nancy Pelosi is quoted making that same point on the Samaras interview.

But Trump’s question “do you feel as well-off now as you did when I was president four years ago” cut through to voters.

Writing in the Saturday Paper – Australia must reject Trump’s chaotic vision – John Hewson goes along with Pelosi, pointing out that the Biden administration has done well on economic management. Inflation and interest rates are heading down, there has been strong jobs growth, and productivity growth has been strong, restoring many industries to competitiveness. “The US economy is probably in the best shape of any globally” he writes. Trump’s policies on immigration, on tariffs, on repealing Biden’s industry policy measures, are likely to result in significant and painful inflation, he notes.

But that hasn’t come through to the electorate.

While the state of the US economy after four years of Joe Biden as president is reflected in the data, that was largely irrelevant to voters. Their verdict had more to do with how they felt about their circumstances.

In last week’s roundup there was a link to Mark Kenny’s Conversation contribution Can a “Trumpist” approach to politics work in Australia?. Samaras thinks it could.

In the Samaras interview Steve Cannane pointed out that our low-paid workers have much better income protection through national minimum wages and awards than their US counterparts. Also in the US, by some estimates real wages for the working class have been going backwards for decades. That decline is traceable to the neoliberal policies first pursued when the Reagan administration 60 years ago put an end to the remnants of the New Deal. The ABC’s Ian Verrender is of a similar view in his post on the US election:

What occurred last week wasn't merely an electoral backlash to a cost of living crisis, although there's no doubt that was a factor.

Trump's re-election, rather, was a revolt against economic policies that have fundamentally reshaped the global economy during the past 40 years, and that have left millions disenfranchised and uncertain about their place in the world.

Writing in Pearls and Irritations Joseph Camilleri describes the way America’s political class is seen by those millions living a precarious existence : Trump’s America: ecstasy or agony?. He sees Trump’s victory as “a sure sign of a slowly decaying society where frustration, anger and bewilderment are at epidemic proportions”.

But voters don’t study economic history or compare their lot with voters in other countries. Nor do they pay much attention to public policies that are slow to take effect. Short-term experience counts.

The Albanese government faces two challenges. One is to assure the electorate that its policies are getting real wages moving again and to remind the electorate that the Coalition has no policies that see real wages rising faster – in fact the Coalition’s policies could set real wages back. The other challenge is to head off the Trumpian line, already given a test run by Dutton and Taylor, “do you feel as well off as when the Coalition was in office?”

A response to such a loaded question is provided by the ABS Wage Price Index, released on Wednesday. That index has shown a significant pickup in real wages in the last quarter. In fact it has been clawing its way back up since its low point in March 2023.

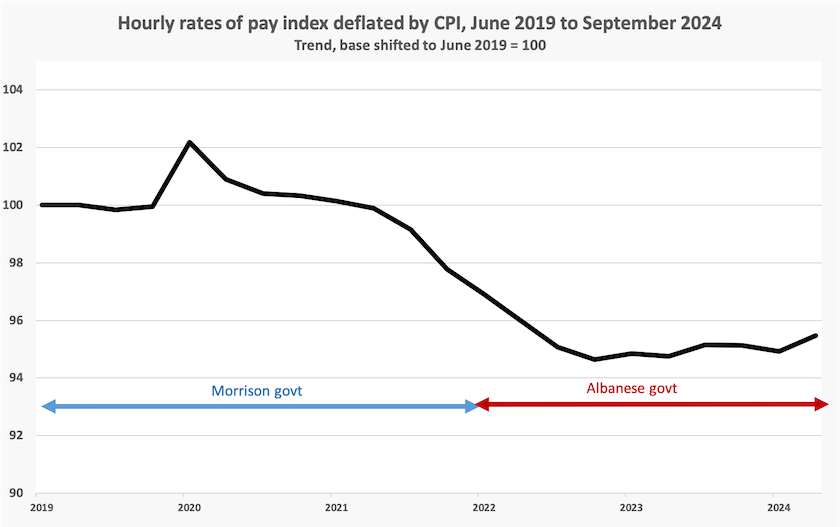

Recent movements in this index are shown in the graph below, which converts the Wage Price Index data to real terms, using the CPI as a deflator.

A partisan approach to this data would be to point out that on the Coalition’s watch, from June 2019 to June 2022, real wages fell by 3.1 percent. (Note that this base precedes the Covid bump by a year). By contrast, on Labor’s watch, from June 2022 to September 2024, real wages fell by only 1.5 percent. In fact, since the low point in March 2023, real wages have slowly risen – by 0.9 percent in trend terms. Repairing the economic damage left by the Morrison government will take some time.

That should be the rejoinder when Dutton and Taylor use their Trumpian “do you feel as well off?” line. In fact it Treasurer Chalmers is already making the same point, according to the ABC’s Tom Crowley: Labor is cheering on wage rises, but if there's no rate cut, will voters even notice? Voters credit themselves for wage rises, while blaming the government – the current government – for price rises.

The full story is more complicated, of course. The rapid fall in real wages in the post-Covid period resulted from the Morrison government having over-stimulated the economy, the war in Ukraine, and post-Covid supply disruptions. It would be unreasonable to blame the Morrison government for this: governments around the world over-stimulated their economies. The more serious problem, that sees real wages 4.5 percent lower than they were in 2019, relates to a long period, mainly on the Coalition’s watch, when governments neglected structural reform, allowing productivity to fall, and when they ran loose monetary and fiscal policies.

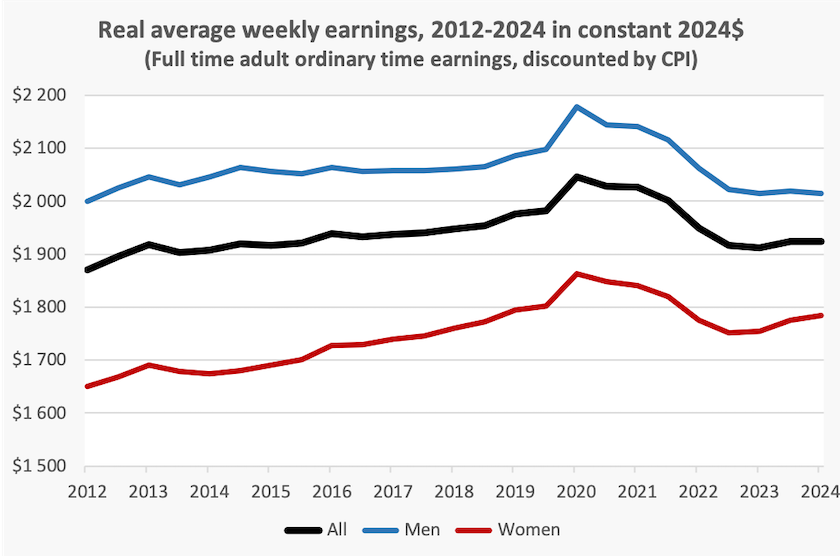

Another indicator of the experience of wage-earners in Australia is the ABS report on Average Weekly Earnings, The source of that series is different from the data used in the Wage Price Index, but the two series tend to move in lock step.

This series, brought to real terms using the CPI, is shown in the graph below. It is not as up-to-date as the Wage Price Index (the last data point is May 2024), but it shows an important gender difference in earnings.

Men’s earnings seem to be have fallen back to where they were in 2012 (the start of the present ABS series), while women‘s earnings seem to be on the same growth trajectory as they were in the pre-pandemic years: notice the difference between the red and blue lines in the post-pandemic period.

These are the complexities of the labour market – complexities that that are difficult for governments to explain to voters. But Dutton and Taylor show no inclination to engage in a debate about the drivers of real wage growth – or, for that matter, any serious consideration of economic structure. Just as American voters believed that Trump would be a better economic manager than Harris, in Australia voters believe that the Coalition is more competent at economic management than Labor. We can expect Dutton and his acolytes to exploit that same misconception, and to make a particular pitch to male voters.

There were at least two other strong issues in the US election – immigration and decline in the rustbelt states.

We don’t have a long and porous land border with a poor country, but we have our own immigration challenges as Abul Rizvi explains in a presentation last week to the Royal Society of New South Wales – Australian immigration policy and the federal election. Both main parties and partisan journalists are throwing numbers around, without distinguishing between aspects that government can control and those that are out of the government’s hands. Both main parties are making unrealistic promises about how they will reduce net migration.

There is something very vivid about desperate people crossing the Rio Grande. It’s harder to fashion a scare campaign about students who don’t go home when they finish their courses, particularly when there are Coalition-aligned lobbies seeking workers. While Trump was able to shout about immigration with racist overtones, Dutton will probably resort to the dog whistle.

Nevertheless, as Rizvi points out in a contribution in Pearls and Irritations – Dutton’s failure on border protection – Dutton will try to blame the government for supposed failures in immigration and border security. With help from radio shock jocks and the Murdoch media he will continue to criticize Albanese for not fixing up the mess he left the incoming government, in spite of his poor record on immigration integrity, and his government’s lax attitude to issuing student visas, often to study in shonky courses crafted by immigration entrepreneurs.

Trump made a successful appeal to the rustbelt states, where there were once well-paying jobs in manufacturing industries. We never had such a large manufacturing sector as the USA, which means we haven’t experienced the same decline. Nevertheless there are urban regions, in the northern and western suburbs of Melbourne, and the northern suburbs of Adelaide, where the automobile industry was once prominent.

Electorates in these regions – Gorton, Calwell and Scullin in Melbourne, and Spence in Adelaide – are held by Labor with more than a 10 percent margin after preferences, but the Liberals and their allies in One Nation and Palmer’s United Australia Party made significant inroads into these electorates in 2022. In that election the combined One Nation plus UAP vote was more than 15 percent, a result seen in parts of rural Queensland but not otherwise in urban regions. It is hard to see the Liberal Party emulating Trump in advocating tariff protection but they will undoubtedly continue their pitch to voters with low levels of education in poor urban and rural regions.

Writing in Inside Story – It’s no time to lose our heads – Paul Strangio assesses the probability of Dutton adopting an all-out Trumpian strategy in the runup to the next election. He summarises Dutton’s likely approach:

In imitation of Trumpism but also amplifying Howard’s strategy, Dutton is focusing his party’s appeal on the outer suburbs and rural and regional Australia. He appears to envisage a future in which the Liberals become the natural home for economic battlers and especially the lower-educated, in a mirror of the Republicans’ growth constituency in the United States.

He warns Dutton and those in his party who are advocating a hard-right strategy that “the forces of extremism can whirl out of control”, however. He also suggests that Labor is less infected by the ideology of neoliberalism than the US Democrats. But he concludes with a warning for our timid government.

Labor must treat the challenges of this time with urgency and conscientiousness. This demands a degree of boldness from the government, and needs the prime minister to spread his wings – if, indeed, he is capable of growth in office. It requires policies that don’t merely tinker at the edges of inequalities but extend to systemic change with a real impact on the welfare of voters. And it needs a dexterous language with emotional freight that binds constituencies together and is attentive to the fact that disadvantage and disempowerment comes in different guises, economic, cultural and identity based.

The emergence (or re-emergence?) of Australian Nazis

The ABC’s David Escort, Mike Lorigan and Alysia Thomas-Sam report on Nazis and others on the extreme right in Australia. They have also contributed to a 730 segment: The disturbing rise of the far-right in Australia.

The images of hooded gangs displaying banners claiming Australia is for the white man, and the recorded vile language of young men praising Hitler, are confronting. The conspiracy theories peddled by the extreme right come across as ridiculous, but there are plenty of people who take them seriously, and for some they can be a motivation for terrorism.

Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke expresses his views: “I don’t care how they describe themselves: they’re criminals.” “If you hate this country, leave.” “Some people try to claim free speech when what they’re actually offering is a recipe for hatred – they are trying to attack the fabric of our country.”

Is the extreme right really on the rise, or have recent events emboldened it to come out more in the open? Should we be worried by the revelation in the Essential poll taken just before the US election that revealed 44 percent of Australian men would have voted for Trump if they could, compared with 23 percent of women?

In recent times we have experienced Peter Dutton portraying the Voice as an issue dividing Australia by “race”. It was actually about the original owners of this land – nothing to do with “race”: why did he raise the discredited Nazi concept of “race”? Trump’s statements have energized misogynists and racists in America: they have surely done the same to some young men in Australia.

We should remember what we have learned from the rise of the National Socialists. Hitler didn’t conjure up anti-Semitism and racism in Germany. Rather he gave those sentiments, which were already dormant, permission to flourish and multiply. He was helped by prominent Germans who failed to identify and speak out against his tactics.

Perhaps what rabble-rousers like Trump and Dutton are tapping into are economic developments leaving poorly educated “white” men behind. Women outnumber men in university graduation. Children of immigrants do better in school grades than children of native Australians, contributing to the fears about “replacement”.

Criminalizing Nazi salutes is a useful move, but a systemic policy approach may have to address the way we bring up children, particularly boys and young men. Are our school systems too gender-separated? Do we valorise aggression in male-dominated sports? Have some in so-called feminist movements left young men feeling unwanted and disrespected?

Opinion polls and political tactics

Campaigning at the margin

So far political parties around the world have been trying to work out what issues were prominent in the US election and how they may resonate in their own countries.

Exit polls have been the source of most of these findings. In any country with voluntary voting (i.e. most countries), opinion polls have a bias, in that they reflect the views of people who have voted. They tell us nothing about people who have chosen not to vote.

On Late Night Live last Monday, in his regular appearance, Bruce Shapiro points to evidence that around the country, turnout by those who usually vote Democrat was low. Overall turnout was high by American standards, but down somewhat on the 2020 election, perhaps by as much as 3 percent.[1] The number of people turning out to vote for Trump was more or less steady: it seems that his campaign did not result in any significant net gain in supporters. The difference in turnout is largely explained by Democrats staying home: Bruce Shapiro's America: why the Democrats lost. (15 minutes)

Shapiro notes that the Trump campaign was all over America – he even held rallies in New York and California. Harris and her team, however, concentrated on the seven “swing states”. Shapiro suggests the message many voters drew from this was that Trump cared about all Americans, Harris cared only about those who could tip the scales.

OK, we have compulsory voting in Australia, but we have an entrenched political practice by the main parties of concentrating on marginal electorates. Compulsory voting means that we don’t have the option of staying at home, but unlike Americans we have the option of voting for more than two tired old parties.

That’s something for the psephologists and political scientists to study: there may be some lessons for our old parties.

How our government s travelling

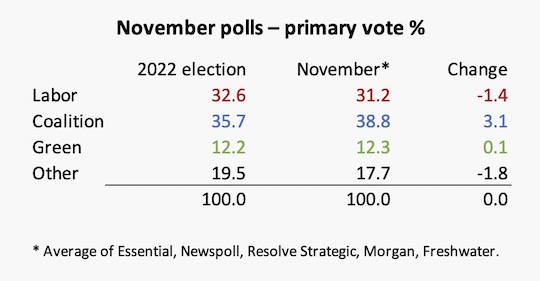

Anyone following the mainstream media over the last few weeks would believe that the Albanese government is in terminal decline.

That’s not what the polls are telling us. The table below shows theaverage of the primary vote in polls conducted over the last month. At this stage in the cycle being behind its election-winning vote by one or two percent is not a great worry for any party. The Coalition vote is up by three percent: if that translated into a uniform two-party preference swing it could take seven seats off Labor – seats with a margin less than three percent. But it’s possible that the Coalition is gaining support in the opinion polls from other parties and independents. Note, in the table, that support for “other” is down; this may simply reflect the fact that national polls are poor at picking up support for independents.

These polls were all conducted before the US election. William Bowe on his Poll Bludger site reports on a Resolve Strategic poll taken straight after the election, that finds, among Australians:

- 26 percent rate Donald Trump positively while 55 percent rate him negatively;

- 41 percent rate Kamala Harris positively while 25 percent rate her negatively;

- 40 percent believe Trump’s election will be bad for Australia while 29 percent believe it will be good.

In the previous Essential poll, just before the election, 33 percent of Australians said that if Australians were eligible to vote in the US election, they would vote for Trump. In fact 47 percent of Coalition supporters said they would vote for Trump.

1. Full results are not yet in, and there are different figures on turnout depending on whether they refer to people of voting age or people who are enrolled as voters. See the regularly-updated Wikipedia entry on voter turnout. ↩