Other economics

Is Australia an extractive or a productive economy?

The mining industry is “the basis of our strong economy”.

That’s hardly a contentious assertion: many would see it as a straight statement of fact.

Nationals MP Bridget McKenzie said it on a Radio National interview defending Peter Dutton’s trip to Bali in Gina Rinehart’s airplane, freely admitting that “the Coalition are the friends of the mining and resource industry”, and asserting that the industry is the principal contributor to our public revenue.

That point about public revenue was a dig at the ABC as a tax-funded public broadcaster, and it is quite wrong: the mining sector contributes only about 8 percent of Commonwealth taxes.[1]

But is it right to assert that the mining sector is “the basis of our strong economy”?

The mining sector certainly contributes about 60 percent of our export earnings, but is it a source of economic strength?

Or is our dependence on mining a sign of economic weakness? Is Australia suffering from the “resource curse”?

This idea is a strong theme in Ken Henry’s address to the Royal Society of New South Wales: Inequality in Australia. (You can go straight to his speech, which starts at 6 minutes after an introduction and concludes at 50 minutes before Q&A.)

His main point is about how our economic structure – the economic structure of a country relying on resource extraction – has contributed to inequality, particularly an inequality in capability, to use Amartya Sen’s framework. In large part this is because of the extractive sector’s effect on our terms of trade and our exchange rate, to the detriment of our trade-exposed industries, including manufacturing, leaving us with a lopsided economic structure.

Inequality in capability leads to inequality in wealth, which, as Thomas Piketty explained, has its own self-perpetuating dynamic.

Henry calls for tax reform. He seems to be too modest to refer to his own 2010 Review. Rather he refers to the 1975 Asprey Review, the principles of which drove the Hawke-Keating government’s tax reforms (partly reversed by the Howard government). He refers to our present tax system as “a conspiracy against future generations”.

As a vision for Australia he refers to the 2012 White Paper “Australia in the Asian Century”. Upon being elected in 2013 the Abbott government ordered that it be pulped (presumably because the White Paper was not sufficiently deferential to Britain). Abbott never quite got his head around technology, and fortunately it is preserved on the Australian Policy Online website. That vision is captured in the White Paper:

… as a nation we must do even more to develop the capabilities that will help Australia succeed. Our greatest responsibility is to invest in our people through skills and education to drive Australia’s productivity performance and ensure that all Australians can participate and contribute. Capabilities that are particularly important for the Asian century include job-specific skills, scientific and technical excellence, adaptability and resilience. Using creativity and design-based thinking to solve complex problems is a distinctive Australian strength that can help to meet the emerging challenges of this century.

Those ideas are repeated in Henry’s speech. In all probability he had a hand in drafting that White Paper: its message is as strong and as relevant as it was in 2012. In fact the message goes back to Donald Horne’s 1964 book The lucky country, and has been taken up many times since, for example by the Centre for Policy Development in its 2013 book Pushing our luck: ideas for Australian progress.

As Bridget McKenzie confirms, Henry’s vision is not shared by the Coalition. Their idea for the Australian economy is for a few more years of economic growth based on resource extraction, the benefits of which will flow to an already-entitled plutocracy, while we slowly slip into an extended period of low productivity, low wages, and social division, as once-prosperous Argentina did last century.

1. See Budget Paper 1. The mining sector contributes about 40 percent of corporate taxes (Page 176), and corporate taxes contribute $143 billion out of total tax receipts of $692 billion (Page 180). That means mining’s contribution is about 8 percent of Commonwealth taxation revenue (0.4*142/692). ↩

The Reserve Bank digs in, threatening its own legitimacy

There were no surprises in the Reserve Bank’s decision to hold the cash rate at 4.25 percent.

“Underlying inflation remains too high” it stated, unswayed by the headline figures, which were influenced by “temporary cost of living relief”. (How do they know it’s temporary?)

Their main concern is that “underlying inflation (as represented by the trimmed mean) was 3.5 per cent over the year to the September quarter. This was as forecast but is still some way from the 2.5 per cent midpoint of the inflation target”.

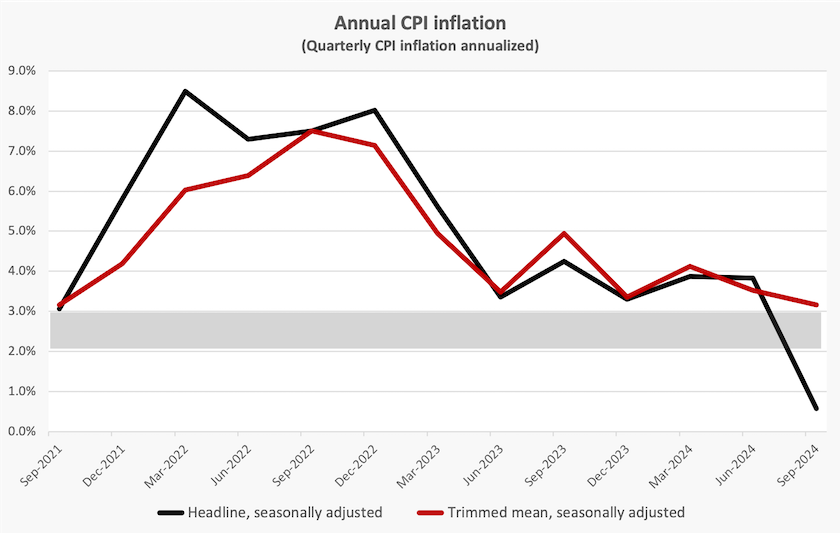

So let’s look at those figures for headline CPI inflation (black) and trimmed mean inflation (red), shown below.

Indeed the trimmed mean is above the headline inflation, which is now down to 0.6 percent. The trimmed mean in the September quarter, the latest CPI data available, was 3.2 percent, just above the Bank’s 2 to 3 percent comfort band (grey area).

But didn’t the RBA state that the trimmed mean was 3.5 percent, not 3.2 percent?

Both figures are right, but that higher figure of 3.5 percent is the rise in the CPI over the whole year to September. The 3.2 percent is calculated from the September quarter only – taking the rise in the September index and annualizing it.[2] If CPI inflation were fairly steady over the year, use of the figure over the previous 12 months may not matter, but when CPI inflation is falling it is a definite overstatement of the rate of CPI inflation.

It is reasonable to ask why the RBA deliberately chooses a method that overstates inflation. Is it really seeking some ex-post rationalization for its hard-line decision, even though doing so contributes to a higher-than-necessary expectation of inflation?

In its announcement the RBA states that “policy will need to be sufficiently restrictive until the Board is confident that inflation is moving sustainably towards the target range”.

Not in the target range, but towards the target range. Isn’t that what the red line is doing?

To return to the start – the black line – the RBA hasn’t fully explained why it’s uninfluenced by that figure.

In a class on economics statistics students would be urged to look at data that ignores policy changes such as energy rebates, and to look for economy-wide indicators of inflation (which is one reason why the CPI is a poor indicator of inflation). There is some textbook purity in the RBA’s choice of a trimmed mean.

But as Peter Martin points out in the Saturday Paper— Inflation and the RBA rates debate –that academic purity ignores the institutional reality of Australia’s setting, because many contracts and less formal agreements are written in terms of headline inflation. It is a more consequential figure than the more academically pure figure of the trimmed mean. The headline figure is influential in driving policy expectations (until the RBA comes along with a figure with a bias to overstatement).

Peter Martin’s article is also a warning about the RBA’s record in the timing of its changes in rates: it does not seem to understand the lags in the system.

Of course the RBA is concerned with more than a single inflation indicator: it also takes into account signs of general economic conditions, particularly signs that the economy is under pressure from excess demand. Its Statement of Monetary Policy paints a picture of an economy that has virtually ground to a halt. It notes that both consumption and investment are weak, and it notes that productivity is weak, weighing on the economy’s supply potential.

But it doesn’t link these findings to its own decisions – to the probability that productivity is down because private investment is down, and that investment is down because the RBA has been obsessed with raising interest rates. Rather, it seems to be concerned that the unemployment rate is too low, that workers are enjoying too much power in the labour market. That perspective fails to acknowledge that when the labour market is close to full employment, workers find it easier to shift from low-productivity to high-productivity employment.

The RBA stresses its independence, but in the mind of many it is coming to be seen to be taking a partisan stance. Its statement that it “do[es] not see inflation returning sustainably to the midpoint of the target until 2026”, could be read in political circles as a determination to hold rates until a Coalition government is elected. It seems to be oblivious to the need for the management of any public sector institution to retain legitimacy in the eyes of the voting public. As we have just seen in the US there is now the possibility that executive government will take over the setting of interest-rates from the Federal Reserve. With the ascendance of populist politics in our own country, we face that risk.

2. The September quarter trimmed mean index number was 138.2529, up from 137.1807. Using the standard formula for annualization ((138.2529/137.1807)^4) – 1.0000 = 0.3163, or 3.2 percent rounded. ↩