Rebuilding Australia’s resilience

How we coped with a shock – Covid-19

Vaccine lineup, Melbourne

Let’s cast our minds back to March 2020, when Covid-19 hit the world. The scenes out of Italy and Spain were terrifying. The disease had an apparent mortality rate of 12 percent and health care workers were succumbing to Covid, while their still-active colleagues were engaged in a brutal triage. It was is if the world had been re-visited by the horrors of the Justinian Plague.[1]]

In coping with this shock our geography gave us more options than were available to other countries: we live on an island and within that large island some of our population centres are well-separated from one another. But as in other countries we were unprepared, because we didn’t know what had hit the world. Was this something that could be eradicated as had been the case with smallpox? Would it follow the path of other viruses that tended to weaken in severity? Could a vaccine be developed, and if so how long would its development take? Who was vulnerable?

In Australia there were questions of responsibility. The Commonwealth had constitutional responsibility for quarantine, but that had lapsed; our health care arrangements were split in odd ways between the Commonwealth and the states; and although we had a history of good public health initiatives, there was no clear locus of public health responsibility.

It’s unsurprising, therefore, that the emphasis of the Commonwealth’s report COVID-19 Response Inquiry is on preparedness, including a recommendation for the establishment of a Centre for Disease Control.

Finding the report

It’s quite hard to navigate the Commonwealth’s websites, where they have three different versions of the report in two locations. The main page – COVID-19 Response Inquiry Report – has a link to the 839-page full report, and to a patronisingly dumbed-down document “Things we need to do to get ready for the next pandemic”. For those with a general interest in public policy the most informative document, linked on what appears to be an orphan site, is the 63-page report COVID-19 Response Inquiry Summary Report: Lessons for the next crisis

In response the Health Minister Mark Butler has announced that the government will establish a Centre for Disease Control.

The report goes much wider than that in its findings and recommendations. It is really an account of how Australia coped with a severe shock. Writing in The Conversation Jocelyne Basseal and Ben Marais of the University of Sydney summarize its findings relating to the response of our health care and public health systems, noting both successes and failures: Australia’s COVID inquiry shows why a permanent “centre for disease control” is more urgent than ever.

Bianca Nogrady, writing in the Saturday Paper – Covid-19 inquiry finds key failings in pandemic response – presents a broader summary, covering issues of communication and trust. To quote:

Another issue the report highlighted was trust, identifying it as one of nine key pillars of an effective pandemic response. The inquiry found that while Australians showed a high level of trust in government at the start of the pandemic, and largely complied with the restrictions imposed on them, that trust eroded over time due to factors such as lack of transparency and evidence behind government decisions, poor communication, mandates, and cross-border variations in policies. In his press conference about the report, federal Health Minister Mark Butler commented that this erosion of trust was not only likely to hamper Australia’s ability to respond to future pandemics, but was negatively affecting vaccine uptake in both adults and children.

The report conveys the impression that trust in government fell away quickly, but it’s hard to find evidence for that. Australia, like New Zealand, stood out for its compliance with tough restrictions, and state governments suffered no voter backlash for having imposed those restrictions. The authors possibly believe that it would have been preferable for governments to have taken a more libertarian approach, as in the US, rather than to have focuse on protecting lives. Or possibly the authors are confusing mistrust with inadequate communication and confusion, particularly over vaccines.

Restoring vaccine uptake is important not only in relation to pandemics, but also for many other diseases. Public opposition to vaccination is often driven by attention to adverse reactions, including deaths. There were 13 or 14 people who died from reactions to Covid vaccines in Australia. That’s about one in two million, but as with air safety, people are less than rational in their understanding of risk. Writing in The Conversation a team of three experts, drawing on the report’s findings, put forward ways to improve vaccine uptake: Trust matters but we also need these 3 things to boost vaccine coverage.

The report points out that the burden of the pandemic and the policy responses, in economic, social and health terms, was not shared equally. “For some groups, the actions of the Australian Government during the COVID‐19 pandemic compounded the negative effect on their health and wellbeing”. (The same could be said for state governments, but the report was specifically focussed on the Commonwealth.) Women and immigrants were among those upon whom the burdens fell most heavily. It also notes the adverse impact on children’s education – impacts with ongoing consequences.

It puts some light around the now-abating round of inflation:

The economic recovery was much stronger than anticipated, reflecting the success of Australia’s public health and economic responses and widespread misjudgement as to the strength of demand following the pandemic. With the benefit of hindsight, there was excessive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus provided throughout 2021 and 2022, especially in the construction sector. Combined with supply side disruptions, this contributed to inflationary pressures coming out of the pandemic.

Writing in The Conversation – The government spent twice what it needed to on economic support during COVID, modelling shows – Chris Murphy of ANU makes the same point, suggesting that if the government could have withdrawn stimulus earlier, the Reserve Bank would not have been so savage on interest rates.

That’s not to accuse the Morrison government of fiscal recklessness. Although many economists and others were critical of the way some of that support was directed to businesses that didn’t need it, and were critical of the behaviour of businesses that failed to repay excess compensation, no-one was saying at the time that the amount of stimulus was excessive. The present government generally refrains from reminding us that the excess fiscal stimulation occurred on the Coalition’s watch, but opposition treasury spokesperson, Angus Taylor, deceitfully asserts that inflation is higher than it should be because of spending by the present government.

On the whole the report seems to downplay the reality of panic and confusion in the early stages of the pandemic, even though it is hard to imagine how there would not have been panic and confusion, even if we had a fully-functioning Centre for Disease Control.

The report is fair in its assessment of key players, noting successes and failures. But it seems to be subject to a hindsight bias, and an implicit assumption that the next pandemic will be similar to the one we have just experienced.

I would like to add my own two-bob’s worth by mentioning a group overlooked by the report, the ABC digital story innovation team. Information coming from governments (state and Commonwealth) on cases, hospital admissions, deaths, and vaccination rates, was patchy and confusing to the general public. Most media had plenty of “newsworthy” stories, but these generally consisted of figures out of context, contributing to dysfunctional complacency or panic. The digital story innovation team pulled together and regularly updated data from all available sources, in a way that the Commonwealth should have done but didn’t.

Another personal comment on the report is that it failed to note the poor understanding among politicians and the general public of exponential growth and decay. If people understand exponential growth and decay they can understand why it is important to control small outbreaks, they can understand why quarantine measures have to be strict, and they can understand how herd immunity sets in as vaccination and immunity develops. It’s not mathematically complex – it’s even covered in Montessori pre-schools.

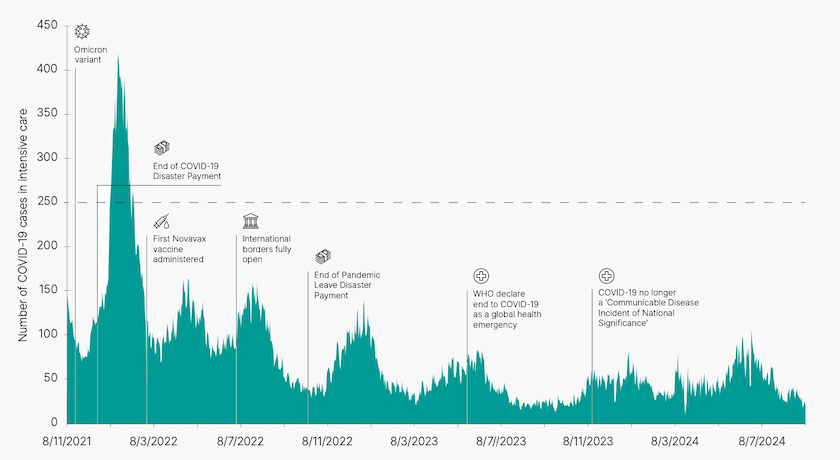

In fact the report shows that in its later stages, the virus was behaving almost in lock-step with system analysts’ models of exponential growth and decay, influenced by the feedback mechanisms of public policy, immunisation, viral mutation, and public behaviour. This is shown in the graph below of intensive care admissions, copied from the report.

It’s a pity the Commonwealth didn’t make this information available in real time. That should surely be a function of the new Centre for Disease Control.

1. he death rate in those early outbreaks was 11.9 percent, but later analysis confirmed that 94.8 percent of those who died had at least one pre-existing disease. ↩

Rebuilding our human capital: modest steps on tertiary education funding

The government has enjoyed a great deal of publicity about its promise that if it is re-elected, it will cut people’s higher-education debts. The proposal has two related aspects – a once-off 20 percent cut to outstanding debt, and higher income thresholds before compulsory repayments cut in. Those repayments will also cut in more gently that at present.

A description of these changes is in a Conversation contribution – Albanese flags radical changes to student debt – with a 20% overall cut and drop in payment rates – by Andrew Norton of ANU.

Norton notes that the cuts (in contrast with the higher repayment thresholds) are once off. It would be strange if this were to be the limit of the government’s reforms: “it would not be surprising if the government also announced reduced student contributions for future borrowers” he writes.

Interviewed on Radio National, Bruce Chapman, the original architect of HECS when it was introduced in 1989, provides his assessment of the changes: Will wiping 20 per cent off student HECS debt make a real difference?. He defends the principle of students contributing to the cost of their education through income-contingent loans. It’s equitable in principle, he explains, but the level of student debt has risen to levels that were never envisaged when HECS was first introduced. Not only are debts too high, but they are also unfairly applied across courses, a consequence of the Morrison government having prioritized STEM courses, and applying much higher fees on humanities and related courses.

Student contributions should be based on expectations of future earnings, he argues. He hopes that one of the first jobs of the yet-to-be-established Australian Tertiary Education Commission will be to adjust course fees in line with such a principle.

The burden of student fees is covered in a paper by Jack Thrower of the Australia Institute: University is expensive: Impacts of rising university costs on young people, who looks at the way student contributions have risen over time, particularly since 2010, and how they apply to different courses. As a proportion of graduates’ salaries they have generally doubled since 1996.

He covers not only the burden of student loan repayments, but also the financial burden on students presently studying. He covers the inadequacy of Youth Allowance (it’s even more miserly than Jobseeker), and he notes that since 2015 there has been a doubling (from about 8 percent to about 16 percent) in the proportion of full-time students who are also working full-time.

There is no doubt that the government’s proposal to ease student debt is a politically clever move, but that doesn’t mean it is bad public policy. It is about relieving the cost-of-living for people who are already relatively disadvantaged by the tax system and who are generally carrying high debt, much of that debt having resulted from government mismanagement of housing policy over many years – mainly on the Coalition’s watch.

The Coalition is highly critical of the proposal, arguing that it is “profoundly unfair” because the cost would be paid by all 27 million Australians while the benefits would go to only 3 million people. That criticism is not unexpected: the Coalition sees tertiary education mainly in terms of private benefits, and does not see community benefits in liberal studies degrees, which is why they were so savage in setting prices for humanities degrees. And it is quite blind to the generational unfairness in our taxation, superannuation and health insurance policies. The government’s proposal on student debt would go some small way towards rectifying this imbalance.

Perhaps the Coalition’s real concern is not about relieving student debt. It is more likely about the government’s probable re-alignment of course fees, making it easier for students to study liberal arts. An electorate with well-honed skills in critical thinking and analysis is unlikely to be attracted to populist political parties offering simple solutions to complex problems.