Politics

Australia’s Trumpist movement – the federal Coalition

Nigel Farage was one of the foreign guests celebrating Trump’s election at Mar-a-Lago on Tuesday. Joining him in the gathering were two Australians, Gina Rinehart and former Liberal Party vice president Teena McQueen.

No doubt Peter Dutton will also be energized by Trump’s victory. He has successfully used Trump’s political tactics to defeat the Voice referendum. In the revelations about politicians’ travel he has made clear his close association with Gina Rinehart: only your closest friends are likely to put their Gulfstream 600 private plane at your disposal.

Writing in The Conversation Mark Kenny of ANU identifies many ways in which Dutton has adopted Trump’s methods. These include accusations that a supposed “woke” left has captured the Labor Party (in reality they’re about as woke as the West Wyalong CWA), contempt for “elites” (whoever they are), attacks on “mad left” journalists, and even an attack on the Australian Electoral Commission because it clarified misinformation about voting procedures in the Voice referendum: Can a ‘Trumpist’ approach to politics work in Australia?

Most US commentators put Trump’s success down to voters’ perception that the Biden administration has been weak on economic management, even though in terms of inflation, employment and growth – the usual trifecta of economic management – the US economy has been doing very well. Voters’ discontent stems from the failure of America’s economic system to distribute the benefits of economic activity.

That failure goes back to 1981, when Ronald Reagan decisively replaced the last remnants of the New Deal with neoliberalism and its associated “small government” mantra. But voters’ political memories are short; when they feel pain they are likely to take it out on whoever is in office.

Here the situation has many parallels. The Albanese government is successfully bringing down the inflation it inherited from the Coalition government, and is slowly working on the task of making up for 26 years, mainly on the Coalition’s watch, in which governments failed to undertake structural reform and allowed housing to become unaffordable.

But as in the US, those who feel economic pain tend to blame the present government. This perception is reinforced by journalists who prattle on about a “cost of living crisis” that seemingly arose when the Albanese government was elected. But as in the US, most Australians are doing rather well. The problem is that the burden of decades of neoliberal economic policies has fallen on the most vulnerable, particularly young people.

The most recent Essential poll confronts us with the similarities between Trump’s and Dutton’s political tactics. It has four sets of questions about how we would have voted in the US election if we had the chance, and what we thought of the candidates. They show that those who support the Coalition domestically are strongly attracted to Trump and his polices.

Harris was favoured by 41 percent of respondents, but a surprising 33 percent of respondents would have gone for Trump, and 13 percent would not have voted. Of those who vote for the Coalition domestically 47 percent would have gone for Trump, 33 percent for Harris. Trump hits it off with Australian men (44 percent), but not with Australian women (23 percent).

There is generally strong agreement (around 60 percent) with Trump’s statements: “Globalisation has gone too far, we need to protect local workers with tariffs on foreign goods”, “Government is fundamentally corrupt and politics has been taken over by vested interests”, “A deep state of unelected officials has too much control”, and “Illegal immigrants should be deported”. Coalition voters were more likely to agree with these statements than Labor voters. In this regard it is notable that Coalition voters are more in favour of tariff protection than Labor voters – 66 percent to 54 percent. (Whatever happened to the party of free trade?)

Respondents thought there would be a negative impact on Australia if Trump was elected: 43 percent “bad”, 29 percent “good”. By contrast they thought there would be a close to neutral impact on Australia if Harris was elected: 32 percent “good”, 26 percent “bad”. There were strong and depressingly predictable partisan differences in the responses to these questions. The Coalition’s supporters believed a Trump presidency would be good for Australia.

Two of them were at Mar-a-Lago on Tuesday night, with Nigel Farage.

The Liberal Party’s battle with independents

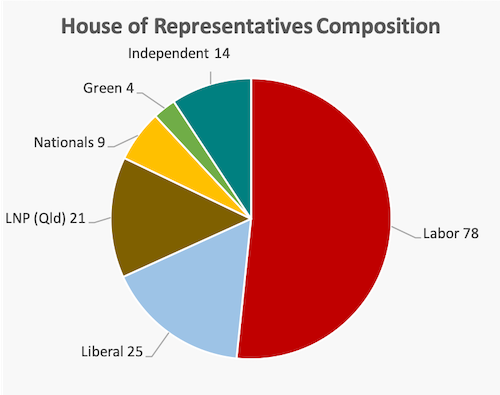

A foreigner unfamiliar with the ideologies of Australia’s political parties, looking at the pie chart below, could reasonably conclude that the Liberal Party is a minor player in our parliamentary democracy, with only 25 seats – one in six – in our 151-member lower house.

OK, the Liberal Party draws on another 30 seats from the Nationals and the Liberal National Party, but that means it is in effect a junior partner in the Coalition. with only a few more seats than the Liberal National Party, a party whose representative base is in Queensland north of the Tropic of Capricorn.

It gets worse for the Liberal Party. It holds only 14 out of 81 electorates in our capital cities, even though 18 million of our 27 million population live in those cities.

No wonder it is adopting Trumpian tactics to try to seize some outer metropolitan seats off Labor.

Similarly it is no wonder the Liberals would like to win back seats from independents who have won them in what once were Liberal Party urban “heartlands”.

Karen Barlow, writing in the Saturday Paper – The teals are ready for an election battle – describes how the Liberal Party is trying to reclaim these seats in a campaign they call “teals revealed”.

The message is that the Teals are really Labor or Greens pretending to be independents. There are voting figures to prove it, because the independents “most often vote with the Greens and far more often with Labor than the Liberals” to quote Barlow.

These figures on voting patterns are generated in two ways.

The first occurs when independents propose amendments to legislation, and the Greens vote in favour of the amendments, while Coalition members oppose the amendments or refrain. Independents cannot help it if the Greens sometimes support good public policy.

The second way relates to a tactic the Coalition uses to generate the voting numbers in support of their claim. Independents propose a legislative amendment generally in line with Liberal Party principles, Coalition members vote against it, and they then put up an amendment that is only slightly different. That scores another point on the voting tally.

Barlow quotes Zali Steggall’s comment on that tactic:

The irony is, if they spent half the amount of time they spend on data and trying to drive up fear-and-smear campaigns on actually coming up with some real policies with some real numbers, like, for example, costings and some kind of evidence around their nuclear policy proposal, voters might actually have something of substance to consider.

That may be difficult for the Liberal Party, however. Its core Parliamentary team – Dutton, Ley, Tehan and Taylor – have established a successful political strategy of fear-and-smear. It worked in the Voice campaign, and they would be reluctant to abandon it now. And if they did decide to engage in debates on public policy, they would find it difficult to craft proposals that could be attractive in Teal seats and in the outer suburbs.

In any event the message that associates independents with Labor and the Greens may be counterproductive, because many independents take a strong stand on issues that social-democratic parties could be expected to support, including administrative integrity, campaign funding reform, whistleblower protection, gambling reform, and strong action on climate change. To many voters the independents are the Labor Party they wanted to vote for, not the politically timid party they put into office. And to many others the independents are the Liberal Party they wanted to vote for, not the hard-right populist party shaped by Abbott, Morrison and Dutton.

The NACC fails on its first assignment

Rick Morton, writing in the Saturday Paper, explains how the National Anti-Corruption Commission failed on Robodebt. His article is about the Report of the Independent Inspector of the NACC, which looked into the NACC’s decision not to investigate referrals of six persons from the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme. This report found that in this decision the head of the NACC had engaged in misconduct. Morton covers the same ground, in less detail, in a Schwartz Media 7am podcast.

That decision not to investigate Robodebt’s key players caused outrage among victims of Robodebt, who believe it means that the public servants and ministers responsible for Robedebt will escape with impunity and anonymity.

The specific misconduct to which the Inspector refers is the failure of the NACC’s head to remove himself fully from the decision not to investigate Robodebt, even though he had a close relationship with one of the six people.

Writing in The Conversation – In failing to probe Robodebt, Australia’s anti-corruption body fell at the first hurdle. It now has a second chance – William Partlett of the University of Melbourne, and a Fellow of the Centre for Public Integrity, sees NACC’s decision not to investigate as “a departure from a long history of anti-corruption oversight in Australia”.

Morton considers the NACC to be a weak body. He believes it got off to a bad start when the government chose to specify its functions and powers in collaboration with the opposition in a “bipartisan” agreement, even though the strongest voices calling for a strong anti-corruption body were the independents. (Does not Albanese, in his bipartisan deals, understand that in Parliament there are more representatives of the Australian people than just the members of two old, tired parties?)

ABC political reporters Tom Lowrey and Courtney Gould explain that the report of the Independent Inspector puts the future of NACC Commissioner Paul Brereton into doubt. Similarly Willliam Partlett has said that Brereton must reconsider his position, but Peter Dutton seems to have thrown his support behind Brereton.

The essence of Morton’s piece is that if the NACC decides it cannot investigate Robodebt, where there is so much evidence of corruption, it is questionable whether it can investigate anything at all.

Some of the NACC’s rationalization seems to be about the definition of corruption, including the question whether a failure to take all reasonable steps to inform a minister of possible illegality is corrupt – a sin of omission in ethical terms.

The public will not be well-served by a narrow interpretation of corruption. The Robodebt Commission shed a sliver of light on a common practice in the higher ranks of the public service that should count as systemic corruption. That is the expectation that public servants will not only serve the government of the day, but that they will obsequiously and unquestionably take on the government’s ideology, and as de-facto party apparatchiks that they will protect ministers from anything they don’t want to know. That’s a long way from the ideal of “frank and fearless” advice.

The Australia Institute is running a petition calling for an independent review of the NACC, and a set of reforms to strengthen it – more power to hold public hearings, strengthened powers for the Inspector, protection against partisan stacking of the NACC Parliamentary committee, and establishment of a whistleblower protection authority.