Poltics

Austria’s election and its challenges for democracy

In Austria’s election last Saturday a party on the hard right, with roots in National Socialism, was the most successful in terms of votes and seats won.

This outcome, coming so soon after swings to populist parties in Germany’s Länder (state) elections, has implications for Europe. In addition the way Austrians now go about forming a government has implications for all democracies, including our own, as we learn to live in a post “Westminster” multi-party world.

First, the numbers.

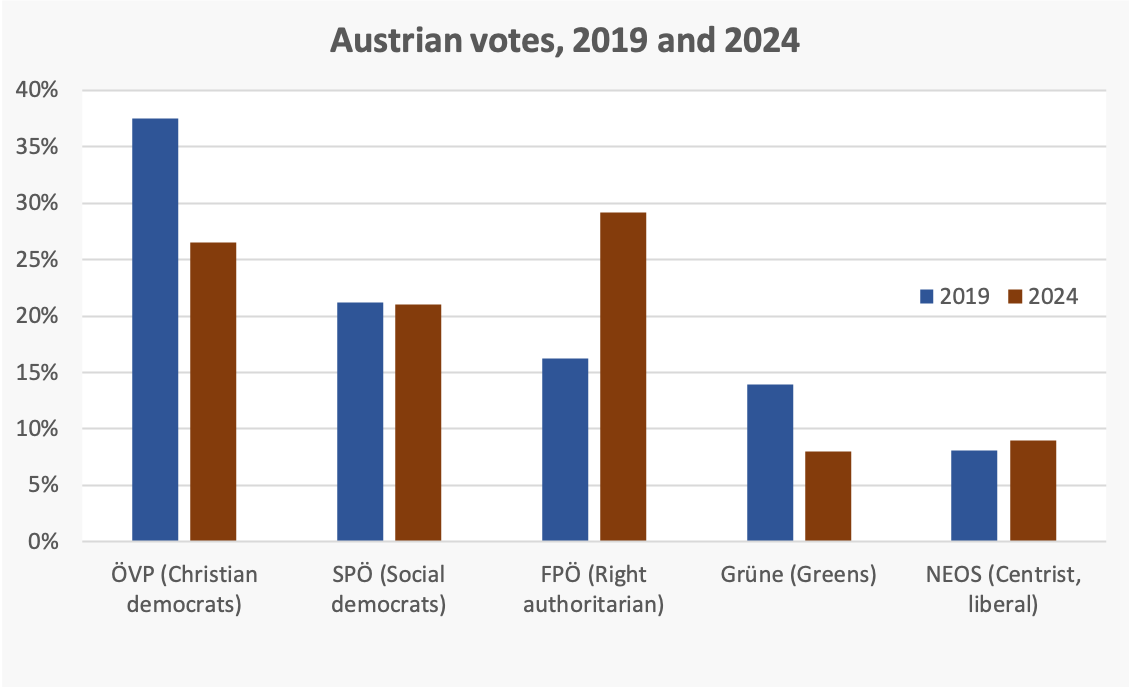

There was a strong swing to the hard right Freiheitliche Partei Österreich (FPÖ) at the expense of the governing coalition of the centre-right Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) and the Greens (die Grüne), on a high (78 percent) turnout. The results, in terms of voting percentages, with comparisons of outcomes in the 2019 election, are showing in the graph below.

That doesn’t mean that the FPÖ will automatically form government. It has won 57 seats, but it would need another 35 seats in order to form government in the country’s 183 seat Nationalrat (lower house).

As Deutsche Welle’s Jane Mcintosh explains, the FPÖ isn’t just any right-wing party: Austria’s FPÖ: A turbulent history. Its first chairmen were former SS officers, and while it initially shook off its Nazi past, during this century it has swung back to a hard-right anti-EU, anti-immigration, pro-Putin stance. The FPÖ has campaigned on a platform of “de-migration”, which involves cancellation of naturalized citizens and sending them to the countries of their ancestry.

There is a tendency to see Austria simply as an extension of Germany, but it is a very different country. It didn’t go through Germany’s intense program of de-Nazification. It is 55 percent Roman Catholic, but that is a deeply conservative form of Catholicism. It is less urbanized than Germany and has many poor regions: cities such as Vienna and Salzburg stand in strong contrast to relatively poor rural regions, where the FPÖ vote was high.

Now for the hard part – forming government

There is a common assumption that in a multi-party democracy the party with the highest proportion of votes or seats, but without enough to control parliament, will form a coalition with other parties that are nearby on a “left-right” spectrum. Because the ÖVP has 51 seats, an FPÖ-ÖVP coalition would see a rightist government with 108 seats.

That is the way the Dutch formed government 224 days after their 2023 election in a coalition of four parties on the right, including Geert Wilders’ far right Partij vood de Vrijheid (Party for freedom). Notice how the hard right latches on to the word “freedom” in Austria, the Netherlands and the USA, as if authoritarians are champions of liberty!

Closer to home, thatt is how New Zealand has cobbled together a three-party coalition in a National, ACT New Zealand, New Zealand First, coalition government. And even closer to home we have two parties on the right in a formal, but secret, Coalition with a capital “C”.

Such coalitions come about only because of conventions, and there is no guarantee in Austria that FPÖ will form government in a right-wing coalition. The ABC’s Radio National has an interview with Matthew Karnitschnig of Politico Europe in Vienna, who explains possible outcomes. One possibility is that the ÖVP will join a coalition only if FPÖ’s leader Herbert Kickl steps down. That is similar to the eventual outcome in the Dutch election, where the coalition agreement was dependent on Geert Wilders not becoming prime minister.

There’s an Australian precedent. At the 1922 election in Australia the Country Party agreed to form a coalition with the Nationalist Party only if Billy Hughes would not be prime minister. We could imagine a similar outcome of our election next year, if independents refuse to support the Coalition unless Dutton and Ley remove themselves from their positions.

But why do parties on the “left” or “right” have to cluster together? Can Austria have a centrist coalition? That is not hypothetical: it is how the outgoing Austrian government was formed, because in the 2019 election the ÖVP chose to govern in coalition with the Grüne, rather than with the FPÖ. An Australian analogy would be a Liberal-Green coalition, leaving the National Party sulking on the cross-bench.

In fact a coalition of the centre is essentially how Germany has been governed at times since 1947, including the present. The Germans still have memories of how the National Socialists won power by holding parties of the centre-right united against the left.

We could imagine the possibility in Australia of an election outcome where One Nation has won a small handful of seats and the Nationals and Liberals need those seats to form a majority. The outcome could be a government where a party on the far right exercises huge political power, even though its policies are quite unrepresentative of the wider electorate or even of those who thought they were voting for a centre-right party.

Austria’s President Alexander Van der Bellen has told political parties to hold talks to form a government. According to Deutsche Welle’s account of the election one possibility is a ÖVP-SPÖ-NEOS coalition, leaving out FPÖ. They would hold 110 seats and be able to claim legitimacy on the basis that together they have won 57 percent of the vote.

In fact the president has made a very strong statement to the people about how he would like to see the situation resolved.

It starts with what may be considered to be a gentle hint to the parties:

Ich werde darauf achten, dass die Grundpfeiler unserer liberalen Demokratie respektiert warden:

I will take care that the basic pillars of our liberal democracy are respected:

The next words go beyond what we may usually expect from kings and presidents, where he specifies those pillars:

etwa Rechtsstaat, Gewaltenteilung, Menschen-und Minderheitenrechte, unabhängige Medien und die EU-Mitgliedschaft.

for instance the rule of law, the separation of powers, general and minority rights, independent media and EU membership.

That brings to mind the question of how we would solve such a situation in Australia. Imagine a party with the power to complete a right-wing coalition, with a platform of abolishing the Australian Electoral Commission, selling the ABC or making it into a government broadcaster, and forming closer ties with Putin’s Russia. The constitutional crisis would overshadow the events of 1975.

That’s why we should not keep pushing constitutional reform down the track. We need a head of state, appointed by a process seen as legitimate by the Australian people, accountable to the Australian people, respected by the Australian people, and with no loyalty to any other country.

Tasmanian women rally to support the Taliban

Foreign Minister Penny Wong has announced that we will join with Germany, Canada, and the Netherlands, to hold Afghanistan to account under international law, for the Taliban's treatment of women and girls.

At the same time as our government is moving against gender discrimination in Afghanistan, however, a group of women in Tasmania has come together to convince that state’s supreme court that gender discrimination is justified.

The SBS’s Kerrin Thomas covers the case in an article, in which the picture of “ladies” displaying vivid misandric banners, tells most of the story. The men of the Hobart’s Athenaeum Club and the Hobart Club, and the men of the Melbourne Club, must be feeling comforted that there are women in blue vehemently defending the cause of gender separation.