The Reserve Bank, inflation, and all that stuff

The Reserve Bank’s obsession with a magic number

The Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Decision now comes with a videoclip of the governor’s announcement. Governor Bullock introduces the bank’s justification for holding the cash rate target at 4.25 percent with the statement “we considered in detail whether our current settings are sufficiently restrictive”.

That frame says much about the Bank’s priority.

She justifies the Bank’s obsession with bringing inflation back down because “that’s the most important thing we can do to ease pressures on people”.

That concern for people’s cost of living, however, is in contradiction with the bank’s stated concern to bring down the “underlying” rate of inflation. That is the rate of inflation once the effects of once-off movements and short-term interventions are disregarded.

Which is the bank’s concern: the effect on people, or the “underlying” rate of inflation?

Government policies, such as electricity cost rebates, are addressing people’s cost-of-living pressures. So if the bank is really concerned with households, why not cut interest rates now, even if it means the underlying rate will take longer to come down? In any event, not all inflation is bad for households: a modest level of inflation, provided it is matched by nominal wage increases, helps reduce the real burden of household debt.

John Quiggin builds on this point in his Conversation contribution: The RBA is making confusion about inflation and the cost of living even worse. By themselves higher prices aren’t a problem, but the shock of a sharp increase in interest rates is a problem.

Is the RBA chasing a number, the relevance of which it has forgotten? In any event where did that two-to-three target band come from?

Stephen Koukoulas was among economists who believed the RBA would have to cut rates. His economic reasoning was sound, but his prediction was wrong, possibility because he failed to account for the psychological power of an obsession.

Peter Martin believes that the RBA will soon have to cut rates. His Conversation contribution, No RBA rate cut yet, but Governor Bullock is about to find the pressure overwhelming, puts the case for easier monetary policy on the basis of falling household disposable income. In her announcement Bullock admits that household demand has fallen faster than the RBA had expected.

The ABC’s Ian Verrender is among economists who believe that the basic economic model on which monetary policy is based, the supposed trade-off between inflation and employment (the “Phillips curve”), is fundamentally flawed: RBA should stop relying on outdated theory about inflation and employment. When checked against historical data on inflation and unemployment there is no evidence of a neat mathematically-described trade-off.

Jeff Borland of the University of Melbourne warns in a Conversation contribution that the RBA is misreading the labour market in its belief that the published unemployment rate of 4.2 percent is a sign of an overheated economy. He stresses that our jobs market is weaker than it seems, employment having been boosted by some temporary measures: Unemployment of 4.2% is a sign of RBA success, but it might not last. Here’s why.

Australia’s plunge into deflation

The Monthly Consumer Price Index published on Wednesday, the day after the Reserve Bank announcement, shows that in the three months to August CPI inflation fell to 1.0 percent – a whole percentage point below the RBA’s comfort band of two to three percent.

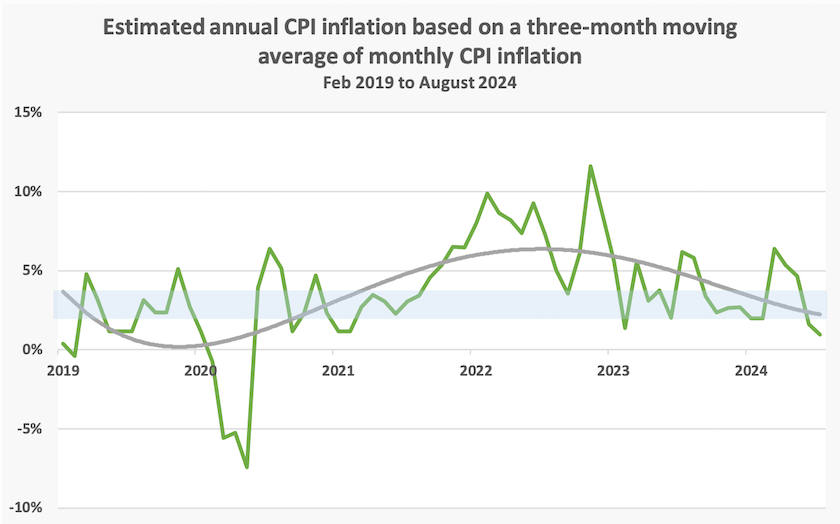

Below is shown the graph which I update every month. The green line is the three-month moving average of CPI inflation, converted to an annual rate, and the grey line is a polynomial trend line. The grey zone is the RBA’s comfort band.

That figure, 1.0 percent, is not the same as the 2.7 percent that the media reports. That 2.7 percent is a measure of CPI inflation over the whole 12 months from August 2023 to August 2024. Mostly it’s history.

We don’t know what inflation is now. Nor does the Reserve Bank, but an indicator based on the most recent three months is likely to be closer to the mark than one that extends over a longer period, particularly when, even by the RBA’s admission, inflation is falling. That’s basic arithmetic.

But in its statement on its monetary policy decision, the Bank sticks to its unsupported assertion that “inflation is still some way above the midpoint of the 2–3 per cent target range”.

It has no authority to state that. It should say “inflation, as indicated by the movement in the CPI over the last 12 months of data, is still some way above …”.

It’s not clear why it persists with this deception, asserting that it can state what inflation is now. That presentation, in the present circumstances, has a bias to overstate inflation. The RBA, by its own account, wants to reduce inflationary expectations, for sound reasons. So why does it deliberately use a method with an overstatement bias?

It is notable that in this last quarter among the items showing the strongest price rises were meat, fruit and vegetables, and insurance – all items that have more to do with climate than with an imbalance between long-term demand and supply. The Reserve Bank isn’t clairvoyant, but it’s surprising that it would not have had a good feeling about these price rises before it met, and realized that they may be driving the numbers higher. Surely RBA staff go to the shops and stand around the water cooler complaining about their insurance bills.

Reserve Bank politics

Jacob Greber of the ABC provides some insight into the apparent tension between the Treasurer and the Reserve Bank over interest rates: Labor is leaning into an assault on the “barbarians” at the bank. It may be great politics, but the economics are trickier. Such tension isn’t new, he explains, but it doesn’t often come out into the open. It’s understandable that in the present situation the government would want itself to be seen as distant from the RBA.

In any event, is there a disagreement? When the treasurer says that high interest rates are smashing the economy, is that not just a re-statement of what the governor says, using a slightly stronger verb?

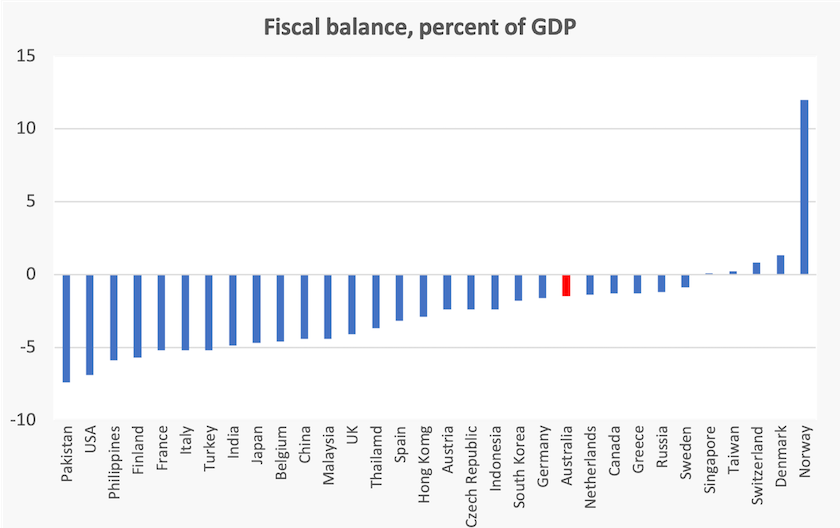

There is a real political tension, however, between the government and those calling for fiscal stringency, including the opposition and other fiscal hawks, who would have us believe that because the government is on some Venezuelan-style fiscal profligacy, the RBA has no choice but to sustain tight monetary policy.

That’s not so. Australia does have a fiscal deficit, but it’s minor in comparison with other countries. The graph below, taken from the current Economist, shows the fiscal balance for all large and high-income countries they list.

When these same fiscal hawks are asked what programs they would cut in order to close our supposedly troublesome deficit, they evade the question, and refuse even to entertain the idea that we might consider raising taxes.

Another political tension is between the government and the Greens. Writing in The Conversation, John Simon of Macquarie University, who once worked at the Reserve Bank, presents a convincing case explaining why the reforms recommended in the recent review of the RBA should be implemented: After working for the RBA for 30 years, here’s how I’d make it more accountable. He argues strongly for the bank having a more open decision-making process and an interest-rate board made up of experts.

Politics are not on his side, however. The Coalition has refused to support the government’s legislation implementing these reforms, even though the reforms are strongly supported by the RBA, and the Greens are blocking them in the Senate.

The opposition’s stance is understandable. A requirement to have a board of experts would make it harder for the Coalition in government to appoint its cronies to the board.

The Greens are holding out for the Government to use its hitherto never-used power to override the RBA and to cut interest rates. Unless they are entirely economically naïve (a strong possibility) they would know that such an intervention would damage our government’s credit rating, and permanently raise interest rates throughout the economy.

A more plausible explanation for the Greens’ stance is that they want the government to be associated, in the public’s mind, with the hardship imposed by high interest rates. This might be being part of a wider strategy of helping the Coalition regain office, so that the Greens could be relieved of the responsibility of having to work with a social-democratic government. It would be an easier and more powerful role for the Greens to be the last line of defence against a hard-right government.

Recessions and inflation explained

The public debate about economics is partisan in nature, and as such tends to treat economic concepts such as inflation, growth, and unemployment as if these are unambiguously well-defined concepts.

Two separate Conversation contributions explain basic economic concepts – recessions and inflation – showing that for both there is a range of interpretation.

Leonora Risse of the University of Canberra asks What’s a recession – and how can we tell if we’re in one?. Many economists suggest that two successive quarters of negative economic growth define a recession – sometimes called a “technical recession” – but there are many other possible definitions, drawing on a range of indicators that are not so amenable to simple definition. Because of our high rate of population growth Australia rarely experiences a “technical recession”, but there have been plenty of periods, including the post-Covid period, in which our per-capita economic growth has been negative.

Risse goes on to explain the Sahm Rule as an indicator of recession. It relies on unemployment data. It looks not only at the level of unemployment, but also at its rate of change – its first derivative in mathematical terms. She shows that the rate of change has been a robust leading indicator in the past and that it is presently rising. The growth in unemployment, from a low base in 2022, is confirmed by ABS Labour Force data.

Similarly Kevin Fox of the University of New South Wales asks What’s inflation – and how exactly do we measure it?. His focus is on the CPI (which is actually only one indicator of inflation). He explains how it is constructed, how it tries to keep track of our spending habits (he has graphs of our changing spending going back 75 years), and how the Reserve Bank and others try to filter out the noise to detect underlying trends.

As the Conversation editors point out, Fox’s contribution is part of a “business basics” series. There is a lot more to be understood about inflation than this basic explanation. His definition of inflation as “a general increase in prices that reduces the purchasing power of money” is in line with the standard texts, but its measurement, and interpretation of any indicators, are fraught with practical and conceptual difficulties. This is particularly so when the economy has been rocked by a pandemic, and when there has been a changed government making modest moves to attend to structural weaknesses neglected by its predecessor.