Other eonomicss

National accounts – they could have been worse

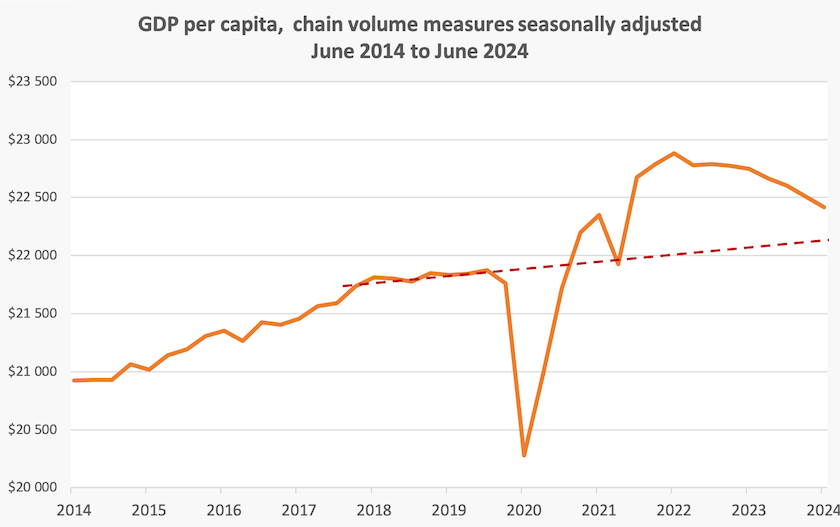

The June quarter National Accounts had no surprises: the Treasurer and financial experts had conditioned us to expect a poor result. This was the third successive quarter in which GDP growth came in at 0.2 percent – a couple of rounding errors away from a negative outcome. More telling, in terms of living standards, GDP per capita fell by 0.4 percent in the quarter, making for a 1.5 percent fall over the year. This indicator is shown below over the last ten years.

The ABS is still not producing trend estimates. The pandemic played havoc with trend models, but if we draw a freehand line (the red dotted line) from the pre-pandemic years, when the economy was growing only slowly, it looks like it may still be a couple of quarters before we come back to that trend.

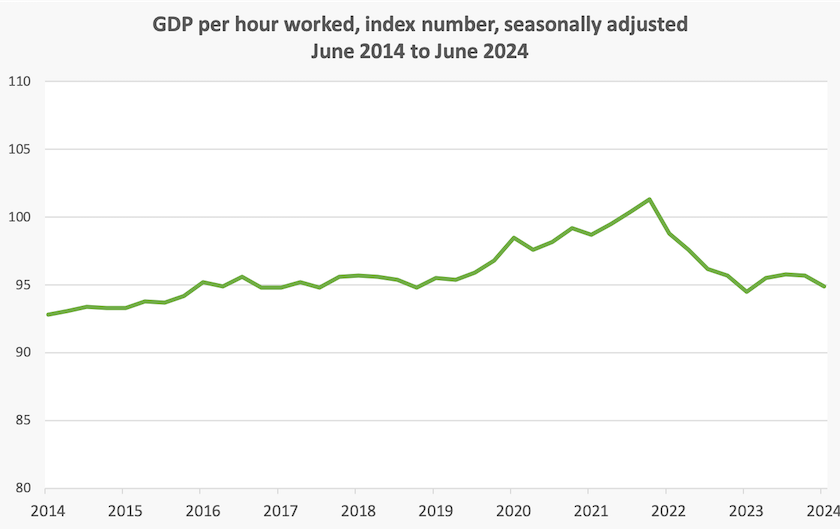

A tentative explanation of these figures, and of inflation indicators, is that the government over-stimulated the economy during the pandemic. It would be catty to blame the Morrison government for this: no one could have gotten it right. But if we are looking for an explanation for this slow economic growth there is a clue in the productivity figures (GDP per hour worked) revealed in the national accounts, plotted in the graph below.

It’s best to ignore the boost in the pandemic years – this resulted from a fall in the denominator (hours worked). The longer-term story is that there has been no productivity growth since 2016: the line may as well be flat from 2016 to the present day. This is symptomatic of a mis-managed economy where there has been hardly any attention to the need for structural reform.

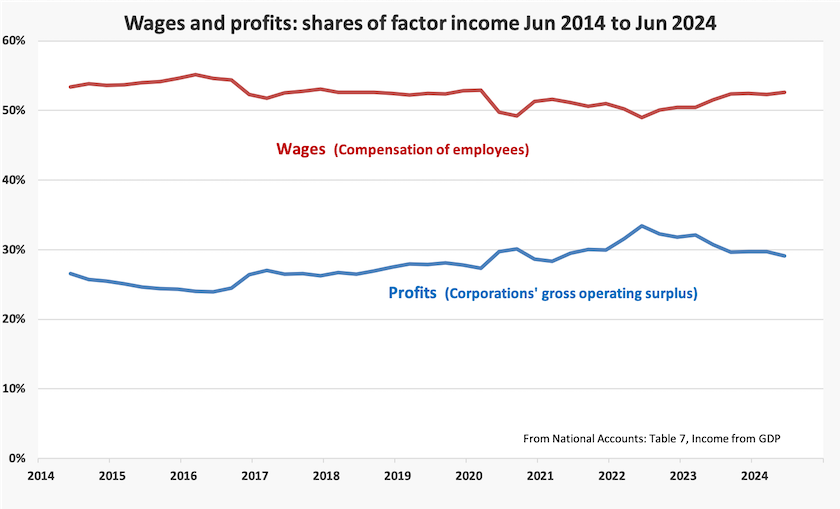

It’s amazing that in spite of this structural weakness there have been faint signs of real wage growth. The ABS in its explanation of the national accounts says that nominal wages rose by 4.1 percent over the year, which is just clear of their estimate of inflation of 3.6 percent (the GDP deflator). This may be explained in part by a small improvement in the share of national income going to wages, shown in the graph below, but most of that shift is probably a result of falling commodity prices reducing corporate profits, there being no evidence that we have a government with an appetite for redistribution.

But for population growth, we would be in the third year of a recession – if one feels bound by the idea that a recession is defined as two quarters of negative growth. Writing in The Conversation, Leonora Risse of the University of Canberra clarifies our thinking about what constitutes a recession: What’s a recession – and how can we tell if we’re in one? We are certainly in a per-capita recession, and if we apply the Sahm Rule, which she describes, we are in a recession. Also in The Conversation Steve Bartos makes the same point: “it feels like a recession for many households” he writes.

Bartos points to the weakness in household spending, which, on a per-capita basis, has fallen for five out of the past six quarters. It’s not as if we have suddenly become frugal and have started saving: we have effectively stopped saving, he notes.

This means there are no signs of an overheated economy justifying tight monetary policy. In fact all these signs suggest that the Australian economy is in the early stage of a recession, however we define a recession.

It appears that there is a difference between the economy as seen by Treasury (and by many businesspeople) and as seen by Reserve Bank. Treasurer Chalmers doesn’t quite say explicitly that the Reserve Bank is “smashing” the economy, but it would be hard to draw any other interpretation from his interview on the ABC on Tuesday.

The Coalition has hit out at Chalmers for attacking the Reserve Bank, and on Radio National Breakfast Dan Tehan made some rather silly comments on immigration in relation to GDP.

The ABC gave opposition treasury spokesperson Angus Taylor an opportunity to give his interpretation of the GDP figures: “Disastrous”: opposition blasts Govt's economic management. Taylor used the occasion to misrepresent the views of economists, and to advocate even tighter fiscal policy than the government is pursuing, which would plunge the nation into a deep recession. He dodged the Coalition’s stated commitment, if elected, to cut $100 billion of government spending.

For some reason Patricia Karvelas gave Taylor an easy run on that interview. She let him get away with saying that inflation is the government’s fault, when it’s clear that the government is working to bring down inflation that had taken off during the Coalition’s watch, as John Hewson reminds us in his most recent Saturday Paper contribution. She refrained from asking Taylor two basic questions: “What, specifically, has the government done to bring about these poor economic figures?”, and “What would you do and why would it be effective?”.

If any academic were to waste ten minutes of ABC airtime to spout the same drivel that Taylor presented in his interview, he or she would soon be on an ABC “do not call” blacklist, but, unable to think beyond the crumbling two-party system, the ABC bypassed the opportunity to get a political interpretation from one of the many articulate and economically knowledgeable independent members of Parliament.

As for allocation of blame, if there is to be any it should go to the Coalition governments that held office for 19 of the 25 years between 1996 and 2022, when it did hardly anything about structural change and refashioned the income tax system to privilege speculation over wealth-generating investment.

A further call for gambling reform

In this roundup gambling is covered in the specific context of Commonwealth-state financial relations. But it is of much wider concern.

The Grattan Institute has just published a well-researched major report: A better bet: how Australia should prevent gambling harm. It covers the same ground about the extent of gambling, confirming once again that we lead the world in terms of gambling losses per head.

It’s about how gambling has pervaded our society: “gambling is everywhere in Australia, unlike the rest of the world”. It distinguishes between those who gamble within limits, and the minority, including many young men, whose lives are wrecked by gambling. The industry is built on “harmful gambling”.

In Australia we have one electronic gaming machine for every 131 people (or one for every 40 households), but unless you live in one of our poorer regions, you won’t be aware of the way they are heavily concentrated in our most disadvantaged suburbs and country towns.

The authors call for reforms, not to prohibit gambling, but to make it “less pervasive and safer”. It calls on the Commonwealth to ban all gambling advertising and inducements, and on state governments, which regulate poker-machine gambling, to implement measures such as mandatory pre-commitment limits.

The specific issue of support for a ban of online gambling advertising in covered in the August Redbridge survey. Among no group surveyed is there a majority opposing a ban. Older people are more in favour of a ban than younger people; Coalition voters are less in favour of a ban than voters for other parties. Otherwise strong support for a ban is close to the same (72 percent support, 16 percent oppose) across all groups surveyed, apart from a curious finding that Catholics stand out as being less enthusiastic for a ban than people of other or no religion. Is there a libertarian movement among Australia’s Catholics?

You can hear the Grattan Institute’s Aruna Sathanapally, one of the report’s main authors, outline its findings and recommendations on a Radio National interview. (5 minutes).

Deadly trucks

In the year to June 2024, 176 people died in crashes involving heavy trucks, an increase of 5.4 percent on the previous year. Deaths involving large trucks constitute 27 percent of all road fatalities in Australia. These figures are from the Commonwealth’s quarterly bulletin: Road deaths in crashes involving heavy vehicles.

Michael West Media’s Andrew Gardiner draws on this data in his post: “Why are they there?” Trucking regulators fail Australian truckies as death toll rises. It’s a criticism of the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator, who seem to be lax about enforcing regulations on truck safety, and who become concerned only when there is a death involving trucks, while paying too little attention to preventing accidents and deaths.

The immediate concerns of the Transport Workers’ Union and of ethical firms in the industry are about truck safety. We have many ancient and poorly maintained trucks on our roads, that aren’t subject to enough inspection. Trucking is an intensely competitive industry, which means there are strong incentives to skip maintenance.

The systemic concerns of unions and trucking companies are about commercial pressures to cut delivery times, resulting in drivers working dangerously long shifts. Proper enforcement of existing regulations would go a long way to improving the lives of truckies and making all of us safer.

Why isn’t this stuff on a train?

Truck accidents have been brought to our attention in recent days following a series of accidents involving two fatalities on the Bruce Highway. The highway is presently closed after two serious truck accidents near Gladstone, one involving multiple trucks and the other an explosion on a truck carrying nitrates that wrecked the road.

The Bruce Highway has a notorious reputation as a dangerous and neglected road. Although it connects many important and growing coastal cities, stretching all the 1800 km from Brisbane to Cairns, only the first 10 percent is built to a four-lane standard.

These accidents are part of what we pay for governments’ illogical fear of borrowing to fund infrastructure, and for our failure to invest in rail freight. There are too many trucks on our roads carrying low-value bulk loads that should be on rail.

Two-tier contracting out – another Home Affairs failure

A reader – a teacher judging by the correspondence – has drawn attention to the Department of Home Affairs mismanagement of adult migrant English services, covered in an Australian National Audit Office reportreleased in June.

When the Department of Home Affairs was created in 2017, migrant English language services were among the functions that had belonged to the Department of Immigration, but as happens in major public reorganizations, many experienced staff who had been running those services were shuffled off to other parts of the department, and improving migrants’ English language skills wasn’t at the top of Minister Dutton’s priorities.

Provision of English language education is contracted to 13 providers in more than 300 locations – TAFEs, some community organizations and some private providers. This is one occasion when contracting out can be justified.

But the department took contracting out to a new level, in that it contracted the supervision of contracts for quality assurance to a private company.

The audit report finds that “the design and administration of the Adult Migrant English Program contracts has not been effective”.

It notes that there have been significant variations to the contracts, made without adequate attention to ensuring that they represented value-for-money.

In what amounts to a mishandling of the whole process the audit finds:

there are deficiencies in the processes by which the department has engaged advisers and contracted the existing service providers to identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes.

One should not be surprised by such a finding in an agency that is so detached from the services that it is delivering that it even has to contract the supervision of those services. When there is such an arrangement, who has the knowledge and skills to supervise the supervision?

The audit report recommends a set of procedural changes, mainly to do with improved contract management practices, rather than any change in the basic two-tiered contracting model. Its final recommendation simply urges the department to “give greater emphasis to monitoring the quality of services being delivered to students by the contracted general service providers”. Carry on a bit better, but don’t change the model.

Missing from the report is any suggestion that departmental staff should improve their knowledge of the task of delivering adult English language services. The auditor’s report is rooted in the idea of the “generic manager” – language services today, road contracts tomorrow, Medicare the following day …

A more through set of recommendations, in line with the Albanese government’s expressed desire to restore the capabilities of the public service, would include a recommendation that department staff improve their knowledge of the program they’re delivering. It might suggest recruiting experts from the sector, staff improving their own skills through further education and staff exchanges, and perhaps a suggestion that the department run a few English language services themselves so as to keep up do date with best practice.