Commonwealth-state economic relations

Roads and hospitals – who pays for what?

Road funding – do we really want the Commonwealth involved in state roads?

The Commonwealth is slashing funding for surface transport, shifting funding to cash-strapped states.

That’s how Martyn Goddard summarizes his post on infrastructure funding: Quietly, Albanese springs a $20 billion budget cut on the states. He’s referring to roads and railroads, assessed by the Commonwealth as being cost-effective and classified as of national significance (i.e. meeting both objectives) as listed by Infrastructure Australia.

Up to now, Goddard points out, the Commonwealth has funded 80 percent of these projects, but the Commonwealth is pushing to shift their funding to a 50:50 basis. He calculates that over five years that will result in the states receiving $18.6 billion less than they would have received under the 80:20 deal, those cuts being roughly in line with each state’s population.

Nice road, but who pays for it?

You can see the agreement the Commonwealth is pushing on its website of land transport infrastructure projects, which spells out the contract terms applying to the states. These include the sharing of road transport safety data (closing a gap in national information), projects’ contribution to decarbonisation, and details such as a requirement to report on women’s participation in construction. The most telling part of the document is in the last few pages, which include fields for state governments to sign. Most of the signature fields are blank, apart from those of Queensland, South Australia and the ACT.

So why would three jurisdictions be happy with a deal that shifts the funding rules, while the other five are holding back? This question underlies the article by ABC journalists Jacob Greber and Grace Burmas: State and territory pressure mounts on Catherine King as transport funding deal risks derailment.

One might expect, in a federation, that the Commonwealth would take prime responsibility for funding interstate roads and railroads, roads of defence significance, and transport links to ports and international airports, leaving the rest to state and local governments.

That is largely the case: of $36 billion road expenditure in 2021-22 the Commonwealth spent $8 billion, the states $22 billion, and local government $6 billion. But the criteria for classifying roads to “national significance” are loose enough to drive a road train through them. If one turns to Infrastructure Australia’s Guide to the Infrastructure Priority List, there will be found criteria that are loose enough for a case to be made around any imaginable project.

We might therefore find the answer to states’ differing stances in the specific state schedules in the land transport project list, linked above. The big interstate projects, such as the $2 billion Coffs Harbour bypass are there, but so too are big projects that seem to be of only local significance, such as Melbourne’s ring road. There are hundreds of small local projects in these schedules, including some of the Coalition’s pet projects, including commuter car parks and “roads to recovery” – selected roads that need upgrading but which don’t align with any idea of national significance.

These could all be worthy projects, with high net benefits, but why should the Commonwealth be involved? If one were to dig through these project lists there would probably be found plausible political reasons why three jurisdictions have signed on, particularly if the projects are overlaid on a map of electorates. Having inherited the Coalition’s pork barrel mechanism, the Albanese government seems reluctant to let it go.

Goddard’s post is about more than roads. He points out that “successive federal governments have had a highly selective idea of what constitutes infrastructure. It’s almost all about transport”. He’s asking why projects such as hospitals aren’t included in these schedules.

The simple answer is that hospitals are a state responsibility. It is no doubt easy to find proposed hospital projects that are cost-effective, but the criterion of national significance is harder to find. Perhaps a large hospital attached to a national medical research centre may pass muster, but otherwise they are state responsibilities.

Goddard’s article raises a basic issue, because it’s easy to find within the Commonwealth’s Infrastructure Priority List plenty of local roads that have no national significance. Therefore why not add hospitals to the list, argues Goddard.

But do we really want the Commonwealth micromanaging all our infrastructure? Maybe it would be better if the Commonwealth were to cut its national infrastructure program back to projects that meet a tighter definition of national significance, and funded the states properly for their local roads, hospitals and other infrastructure needs. It’s as if the Albanese government has learned nothing from the terrible political and administrative mess the Morrison government got in with its funding of local projects.

Labor re-commits to a Morrison boondoggle

Western Australia is contested political territory. In the 2019 election the Coalition held on to 11 of the state’s 15 seats, but lost 5 of them in 2022 – 4 to Labor, 1 to an independent (Kate Chaney).

Shortly before the 2019 election the Morrison government intervened in the distribution of funds that the Commonwealth collects through the GST. Up to that point, since 1933, general-purpose Commonwealth grants to the states had been distributed on the basis of states’ needs and revenue-raising capacity, as determined by the Grants Commission. Overriding the Grants Commission formulae, Morrison broke with that tradition, and placed a floor on Commonwealth funding for Western Australia. The full background to that deal is covered in the roundup of May 18.

As Peter Martin wrote in The Conversation in April, economists urged the Albanese government to scrap the deal, which they estimate will deliver Western Australia an extra $40 billion by 2030, at the expense of the other states and territories.

But the government has no intention of doing that. GST grants are a big issue in Western Australia: they know when they’re onto a good thing. Laura Tingle explains on the 730 Report that Labor is running a campaign to bolster support in the west, hinting (with little evidence apart from some silly suggestions by New South Wales Senator Andrew Bragg on another GST matter), that the Coalition would scrap the state’s special deal. In fact the Labor Party’s political advertisement, not to be broadcast east of Longitude 129, is a scare campaign of a Duttonesque standard, backed by a radio interview in less strident language.

The politics of the situation are straight out of the textbooks. The $40 billion will be noticeable among Western Australia’s 3 million population: $13 000 a head can go quite a way in improving schools, hospitals and roads. The cost to the other 24 million Australians is only about $1 700 a head.

That’s the short-term cost. The longer-term cost is in terms of its contribution to regional disparities. As a large country Australia, partly through institutions of good governance such as the Grants Commission, has avoided regional disparities that are tearing other countries apart. It was grossly irresponsible for Morrison to interfere with one of these institutions, and it is negligent for the Albanese government to refrain from restoring its integrity.

How a poor fiscal deal for states has allowed gambling to proliferate

The roundups of August 17 and of last week covered sports betting and the links between gambling addiction and crime.

That’s only part of a much bigger story about gambling. The ABC’s Ian Verrender has a post reminding us of the wider reach of gambling: Australians lead the world when it comes to gambling and this is what's behind our addiction.

He writes about gambling’s reach into sport and media, the latter going beyond dependence on advertising revenue and into editorial content. He writes about the way gambling has reached into state politics, particularly in New South Wales, where poker machines first made their foothold.

He repeats the finding that Australians lose $25 billion a year on legal forms of gambling. In round numbers that’s $1000 a head, or $3000 per household, and it is disproportionately paid by those least able to bear such losses. He links to work by the Australian Institution of Family Studies, showing in detail the incidence of gambling losses, and our attitudes to gambling. (Spoiler – we believe controls should be toughened.)

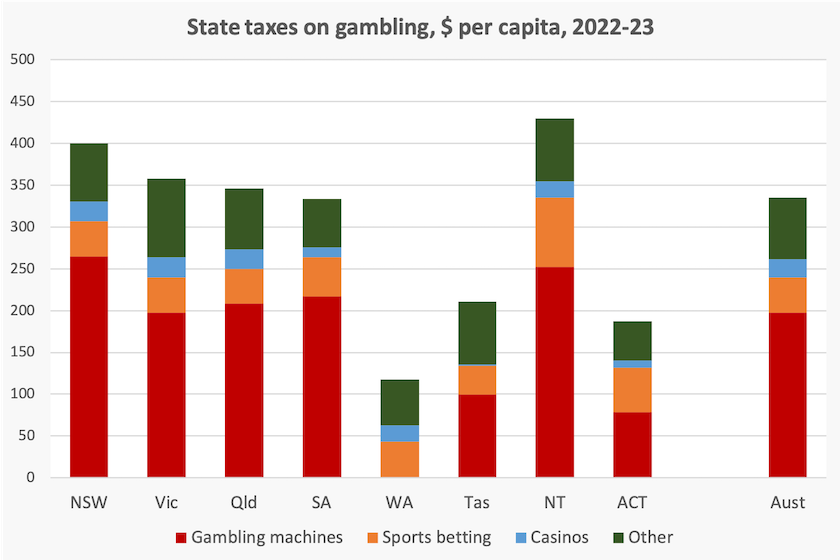

He points out that just as many individuals are addicted to gambling, so too are our state governments. He mentions that state taxes on gambling are around $7 billion a year. In fact that’s a 2021-22 figure. By 2022-23, that had risen to $9 billion, such is the pace of the expansion of gambling.[1]

That means our governments are picking up $9 billion a year, or about $330 a head, in an indirect tax on some the poorest people in Australia.

States need that revenue, but why does it have to come to them in such a regressive way? Why doesn’t the Commonwealth, with its capacity to raise relatively progressive taxes, raise that $9 million in taxes from those who can afford to pay?

Expanding on Verrender’s contribution, below is a graph of gambling taxation, per capita, collected by our 8 state and territory governments. It’s a reasonable assumption that these taxation revenues are related to gambling losses: because governments and gambling companies take their cut from the same gambling losses, it’s a fair bet that a state with high taxation receipts also has high gambling losses.

Note the dominance of gaming machines everywhere except in Western Australia, which has been able to have a no-pokies policy because of the protection of the Nullarbor plain. Bass Strait has likewise given Tasmania some protection. Otherwise poker machines have spread from state by state like a metastasising cancer, because people are able to duck across state borders – a textbook case of the Prisoners’ Dilemma: once one state has poker machines its neighbours have to follow.

Note too how the Northern Territory stands out above the rest, and how it dominates in revenue from sports betting. That’s probably mostly collected from gamblers in other jurisdictions, but it also has high revenue from gaming machines, which would be collected from local people who are not the most well-off in our federation.

A country pub without pokies (The Prairie, Parachilna)

That’s the national geography of gambling. The ABC’s Jason Katsaras has a story illustrating the same point on a more local level: Victorian councils take stand against pokies, but one publican feels left out. It’s about the lessee of the Yackandandah Hotel, located in Indigo Shire, a large area of northeast Victoria that includes Rutherglen, Beechworth, and Tallangatta, and that has banned poker machines. The lessee is right – from most parts of Indigo sire it’s only a short cycle ride to Wodonga, which has no such ban.

What may be good for one business would be bad for others, however. Because of the ban, the money that would flow through the Yackandandah Hotel if it had poker machines stays in the community, to the benefit of other businesses. That’s why a state-wide ban would be to his benefit, and to all other businesses. Better still, a national ban.

And all those other publicans, forced to dispose of their poker machines, would find that customers are coming to drink and eat, rather than playing the pokies and departing broke, unable to afford a beer or a pizza.

1. Sourced from the ABS annual publication Taxation Revenue. ↩