Politics

Dutton’s divisive ways on Gaza

Dutton never lets a chance go by to sow discord and to set Australian against Australian.

This time his chosen issue is about visas for people wanting to flee the hellish conditions in Gaza. Initially he was saying no one at all should be offered a visa, even suggested that visas already granted to those few who have been approved should be revoked. (Getting a visa is difficult enough, getting out of Gaza, whose borders are closed by Israel, is even more difficult).

Recognizing the probable illegality of a ban applying to one country, the Coalition seems to have backed down a little, but is still suggesting that refugees from Gaza be subject to far harsher conditions than have been applied to refugees from wars in Kosovo, Timor, Afghanistan and Syria in times past.

On the Schwartz Media’s 7am program former Immigration Department Deputy Secretary Abul Rizvi explains the hypocrisy in Dutton’s political stance, a stance taken with the sole purpose of making the government look soft on security: Peter Dutton's Palestinian ban is textbook Peter Dutton.

Rizvi explains the various types of visas available to people fleeing wars, and their associated security protections. In fact, in offering only visitor visas to people fleeing Gaza, the Albanese government is far less accommodating than previous governments, mainly Coalition, have been to other people fleeing war zones, who have been given higher classes of visas.

For good measure Rizvi concludes with an observation on Dutton’s performance when he was Immigration Minister:

While he was Immigration Minister there took place the largest labour trafficking scam in Australia’s history abusing the asylum system.

He goes on to describe the operation of that scam, involving 20 000 workers trafficked by criminal gangs and concludes:

On any objective measure Mr Dutton was the biggest failure in terms of border protection we have had in our history.

In a rambling post on the ABC’s website Annabel Crabb gets to another issue in the case, the fact that Dutton brings up the issue ten months after the outbreak of the conflict. The post is in her usual hyper-non-partisan-I-must not-offend-anyone style, but it raises questions about the administrative competence of immigration officials. As they illustrate in their ham-fisted initial denial of a visa to one of Putin’s critics, their bias is generally to excess toughness, even when it causes embarrassment to our country.

Albanese seems to be unable or unwilling to confront Dutton’s outbursts of divisive aggression. He responds in a way one would reply to a critic who puts up a reasoned disagreement to a government’s policy, rather than the way one should respond to a petulant bully out to destroy him. He left it to Tony Bourke to call out Dutton’s behaviour – the behaviour of one who is “irresponsible and a sook” – in an impassioned speech to Parliament.

The Coalition’s ire has been most strongly directed at Independent Zali Steggall, who asked Dutton to “stop being racist”, a claim she repeated outside the protection of parliamentary privilege, and where she was not shouted down by ill-mannered louts from the Coalition benches. The behaviour of those louts is covered in a Guardian article: “Enough is enough”: teal MPs call out “misogyny” of Coalition MPs in question time, which includes a two-minute clip of her speech in Parliament. (You may wish to turn the sound down a little.)

Steggall explains her approach to Dutton’s behaviour in a 10-minute interview on the ABC: “Inherently racist”: Steggall slams Dutton's Gaza visa stance. She sees his statements as “designed to foster fear and hatred of a community group”.

It’s unfortunate that even non-partisan media, including the ABC, tend to use the passive voice and other ways of avoiding any hint of responsibility in describing the conflict over visas for the people of Gaza. They use constructions such as “there have been ugly scenes in Parliament “. But there is clear agency: the initiative to raise the issue was Dutton’s, and he subsequently inflamed the conflict with his statement about “Hamas’s useful idiots”. His behaviour is a threat to peace and good order, and to people’s respect for Parliament and democratic processes.

Dutton’s losing ways on Gaza

Martyn Goddard in his Policy Post suggests that Dutton has made a bad political miscalculation: Dutton’s Gaza adventure turns into electoral suicide.

“The Liberals are betting the election on yet another terrorism scare campaign – but they’re alienating the very people whose votes they must have”, he writes.

Perhaps Goddard is being a bit tough on the Liberals, because this one, like the Voice, seems to be one of Dutton’s captain’s calls. It is hard to imagine Bridget Archer or Julian Leeser, for example, behaving in such a disgusting manner.

Goddard explains the events in and out of Parliament, including the Coalition’s disgraceful behaviour towards Steggall. (See the above post.) He also provides a thoroughly-researched, electorate-by-electorate analysis of the likely electoral consequences of Dutton’s provocative stance on visas for people fleeing the war in Gaza.

He explains the way the Coalition in the past, particularly when John Howard was prime minister, has been drawn to “the seductive attractions of racist politics”. But Australia is not the same country it was in 1996 when Howard was elected, and many migrants who have come to Australia are sympathetic towards people fleeing wars and political oppression. The racist dog whistles that may have worked in Howard’s day (Goddard is not so sure that they did actually work) are likely to be political liabilities now.

As is usual with Goddard’s posts he provides solid statistical support for his arguments. The most compelling data he provides is a table of marginal migrant electorates, showing that they include four of the few urban seats the Liberal Party holds.

The long history of the Voice

Much has been written about the 18-months between the election of the Albanese government and the defeat of the Voice referendum, the erosion of support over that period, and the deceitful campaign of lies, confusion and scare tactics pursued by the “No” campaign.

But there is a longer story behind the referendum, one that goes back to the days of the Howard government, ten years before the presentation of the Uluru Statement. It’s a story of slow and patient progress towards consensus through negotiations. It’s about how those seeking constitutional change, well aware of the difficulties, carefully won support from people in the Coalition, including political conservatives such as Tony Abbott and Christian Porter.

In gaining that support the advocates for constitutional reform made many compromises along the way. The idea that the Voice was a “take it or leave it” proposition that suddenly appeared with the election of the Albanese government, as it was represented by the “No” campaign, is quite wrong: it had been co-designed with constitutional conservatives, senior Coalition politicians, and others whose support its proponents considered to be necessary.

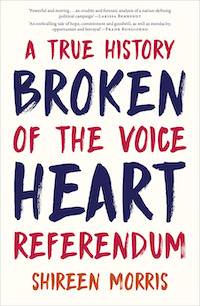

Shireen Morris, of the Macquarie Law School and former advisor to the Cape York Institute on constitutional recognition, presents that story in a session on Late Night Live: The betrayals behind the Voice Referendum loss.

Morris does not lay the blame for that betrayal solely on Dutton: she notes, for example, that while Malcolm Turnbull privately expressed his support for the Voice as an “elegant” solution, in public he presented it as a “third chamber” of Parliament. She notes that many members of the National Party privately supported the Voice, but they closed ranks when the party adopted a hard “No” position. Julian Leeser was one of the few members of the Coalition who publicly stood by his private support for the Voice, and he paid for that principled stance.

We know the rest about the campaign. As Morris says the Coalition, led by Peter Dutton and David Littleproud, worked out that “it would be more politically and electorally beneficial to them to oppose Albanese’s Voice than it would be to do something good for indigenous people and good for the country”.

Their objective was to damage Albanese, and Albanese was probably unwise in presenting the Voice as a key part of his election campaign, which made it easy for the “No” case to present it as a Labor proposal.

Morris’s story is more than one of political tactics. It’s also about the demise of what she calls “good-hearted passionate conservatism” in Australia. The Liberal Party has not always been so bloody-minded. And she does not hold back from stating that she finds racism in Australia.

That’s as much as Morris covers in a 21-minute interview. Her full story is in her book: Broken heart: a true history of the Voice referendum.

Britain’s riots – could they happen here?

Nick Gruen has drawn attention to a short article in Compact, The unravelling of Britain, by Darel E Paul of Williams College.

Paul analyses the causes of the riots, and wonders if the same could happen in other countries in the Anglosphere – countries that share “not only Britain’s language, but a similar liberal polity, economy, culture, and civic national identity”, and that “have undergone similarly dramatic racial and ethnic transformations”.

He concludes that the causes have particularly British characteristics that are much less evident in New World countries. The British are “more rooted to place” – a polite way of saying “parochial”. Britain is poorer and has worse regional disparities than other countries in the Anglosphere.

It’s a reassuring analysis for Australians, but Paul may not be taking a sufficiently fine-grained view of Australia. Any native Australian who is over 60 came of age in a “White Australia”, and many are still not comfortable with multicultural Australia. In fact “White Australia” was a drawcard for many migrants from former British colonies in Africa and for migrants from Britain itself. “White Britain” started to fall apart 25 years before “White Australia”.

Like the UK we too have regional disparities, particularly associated with de-industrialization. Although material living conditions are probably far better than they are in Britain’s de-industrialized regions, there is a sense of discontent in regions such as Adelaide’s northern suburbs and Melbourne’s western suburbs. In these regions support for far-right political parties has been strong.

And just as Britain has Nigel Farage and his Reform Party, we have the federal Liberal Party, exploiting every possibility to polarize and to foment division on lines of ethnic identity.