Housing

How housing is changing

Sunlit plains extended

Up to the late twentieth century the Australian urban landscape was one of endless suburbs of 0.1-hectare blocks with single free-standing houses, interspersed with small blocks of “flats”, generally comprising a few basic units on what had once been a single house block. It was decidedly low-rise.

As one can see in all our cities, over this century high-rise apartments have been popping up, initially in capital cities and in coastal cities such as Wollongong.

Building up, not out

This is close to a global phenomenon. For a long time cities have been sprawling outwards, but over the last few years cities have been growing upwards faster than they have been growing outwards. This trend is confirmed in an article in the journal Nature Cities,Global urban structural growth shows a profound shift from spreading out to building up.

It is most evident in east Asia, particularly China, but is also evident in European and American cities. Sydney is the only Australian city the authors cover. They note that its growth is following the same pattern but more modestly.

The authors summarize their findings:

This shift in growth has important positive and negative implications in terms of sustainable futures. Cities with taller built structure tend to have higher population densities, but these must be co-located with higher job densities to support public transportation to lower per capita emissions and create more walkability. Increasing population density alone is necessary, but insufficient for lowering transport emissions. Furthermore, the built environment does not need to be very tall to foster walkability; smaller block sizes are also important. Emissions aside, more land can be saved for nature with denser cities. However, very tall buildings have high embodied carbon and operational energy needs, require specialized materials and also create unique microclimates.

The research is also summarized in The Economist, in more readable form – Cities used to sprawl. Now they’re growing taller – but that’s behind a paywall. The Economist’s writer adds the point that “dense cities tend to have higher productivity and produce more innovations than dispersed urban areas do.”

After decades of neglect, our biggest cities are catching up on constructing subway and metro systems: just this week a major part of Sydney’s new metro was opened. In Sydney and Melbourne there is a pattern of growth of housing around city stations.

Just over a half-century ago, in 1970, Hugh Stretton wrote Ideas for Australian cities, a liberal defence of the Australian suburb. It was a celebration of the suburban backyard, with its endless possibilities for kids’ play and for adult activities such as keeping chooks and tending a garden. Since then our population has doubled, and the number of people living in capital cities has risen by 120 percent, tending to render the backyard something of a luxury, unless it is on the urban fringe.

The policy challenge now is to preserve the best aspects of traditional and emerging living patterns, lest Australians become housebound in high-rise apartments. The provision of safe, easily accessible open space has to be a major part of our urban policies. So too do policies that reduce the transaction costs when people change their housing as their lifestyle needs change. That means reducing real estate transfer taxes (replacing them with land taxes), and reforming our high-cost real-estate industry. So far, however, state governments have been nervous about making such a change in their tax systems.

Segregtion in Vienna

While we’re on the subject of urban planning, there is a Conversation article by Jua Cilliers of the University of Technology, Sydney What makes a city great for running and how can we promote “runnability” in urban design?. Urban planners often become obsessed with design for public transport, ignoring the needs of pedestrians and cyclists. Even when they do take these other needs into account, they still tend to overlook runners, who have their own requirements. Segregation of cycling and walking paths is usually of benefit to runners, pedestrians and cyclists.

How to provide more housing: whatever we do, don’t elect a Coalition government

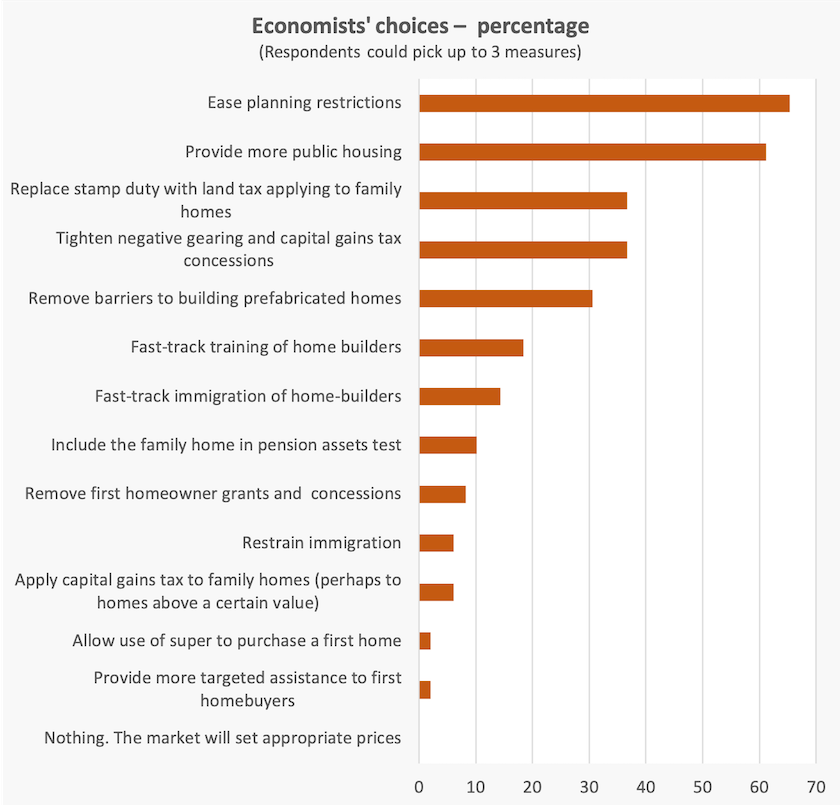

Peter Martin asked 49 economists what they would choose as policy measures to restrain housing prices for buyers and renters. The economists were offered the choice of 14 policies, including doing nothing – leaving it to the market and existing policies.

The results are summarized in a Conversation contribution: “Doing nothing is not an option”’ – top economists back planning reform and public housing as fixes for Australia’s housing crisis.

The chart below shows their responses.

Note the dominance of supply-side measures, and the support for policies to lessen existing demand-side pressure: remove tax concessions, abolish the first home owner’s grant.

Note too, how economists’ preferences differ from those in the Liberal Party’s platform, which includes allowing first home owners to draw up to 40 percent of their superannuation, and raising the limits on low-deposit guarantees. Nor are economists enthusiastic about restraining immigration, one of Dutton’s key ideas.

Although these economists come from a variety of backgrounds, some associated with the “left” and some others associated with the “right”, there is substantial convergence around their policy ideas. They are also consistent with the policy ideas of the housing advocacy group Everybody’s Home, whose Report from the people’s commission into Australia’s housing crisis also stresses supply-side solutions and calls for the abolition of tax breaks that encourage housing speculation.

Not included in the options or in Peter Martin’s article is the possibility of incentives for build-to-rent projects. The government has a bill to encourage build-to-rent investments, currently held up in the Senate by an unholy alliance between the Coalition and the Greens. The Coalition is complaining about the bill’s provisions being favourable to foreign investors – extraordinary hypocrisy in view of their long history of sacrificing our national interests to foreigners. The more probable explanation is that they will do anything to see Labor fail to pass legislation that may help ease our housing shortage.

The Greens’ objection defies understanding. They want to see 100 percent of build-to-rent projects to be for affordable housing. That refers to rents at 70 percent of the market rate or 25 percent of renters’ income. They are ignoring the benefits of socially-mixed communities: do they really want to see blocks of poverty housing? And don’t they understand that even though most housing built in the government’s build-to-rent scheme would not immediately meet their criteria for affordability, anything that increases overall supply will benefit all renters and buyers?

Is their objection driven by economic naivety? Or is it driven by some madcap accelerationist doctrine: the sooner they can get rid of this half-hearted social-democratic government and get Dutton and his cronies into office, the sooner will the resulting unrest and social collapse clear the way for a glorious Green order.

How Singapore does housing

The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens points out that Singapore has achieved a 90 percent home ownership rate, and asks if Australia can learn anything from it.

They have achieved not only high home ownership, but also the price of housing in Singapore has been kept in check.

The short explanation is that the government, through well-designed measures, has ensured that Singaporean homeowners don’t free-ride off an appreciating land value. The value of land appreciates not as a result of the owner’s effort, but because of factors such as a desirable location, and the collective benefits of urbanization.

Hutchens is an enthusiast for the ideas of Henry George, the early-twentieth century economic philosopher who reasoned that the fairest and most efficient way for government to collect revenue was to tax land and other economic rents.

His ideas weren’t exactly popular in parliamentary democracies where representatives are elected by landowners, big and small. To this day any idea of taxing “the family home” is heretical.

But as Hutchens points out, Singapore has been able to put Henry George’s ideas into practice. He draws much of his article on a lecture by Sock-Yong Phang of Singapore Management University, who gave the keynote address at Melbourne’s Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner and Address.

Some may read Hutchens’ article as an endorsement of the idea that people should be able to draw on their superannuation accounts to finance housing. Singapore does have a compulsory saving system, similar in ways to our superannuation system, but Singaporeans are much better savers than Australians, and such policies are not necessarily inflationary in a market with an adequate supply of housing.

To assess Singapore’s success, it is informative to look at how Singapore has performed according to Demographia’s International Housing Affordability tables. The developed world’s least affordable city, according to Demographia’s tables (and some other rankings) is Hong Kong, with a housing price to median income ratio of 16.7:1. Singapore, a city which shares many of Hong Kong’s characteristics, comes in as the 11th most affordable city among the 94 cities in Demographia’s survey, with a price to income ratio 0f 3.8:1.

On that same index our Australian cities come in badly: with a price to income ratio of 13.8:1, Sydney lies just behind Hong Kong, and only a few places farther down are Melbourne (9.8:1), Adelaide (9.7:1), and Brisbane (8.1:1 – the same as London).