Economics

Michelle Bullock goes back to the bush

If you would like an almost complete course in macroeconomics, without all those silly dimensionless freehand graphs, but with a practical grounding, then you could spend an hour with RBA Governor Michelle Bullock where she gives the Rotary Club of Armidale Annual Lecture.

Her speech is titled “Economic Conditions in post-pandemic Australia with a regional lens”. She does indeed provide some regional insights from the Bank’s trove of research, revealing that in that vast land mass some people call “regional”, there has been a huge variation of economic performance – as has always been the case. And she carefully distinguishes between “commutable” regions sprawling out from the capital cities, from the rest of non-metropolitan Australia. It’s refreshing to hear someone applying some rigour and discipline to that over-used and ill-defined term “regional”.

Perhaps the main takeaway from the session is that not all economic wisdom resides in the established universities in our capital cities. Her 25-minute speech is followed by a long open discussion session, with questions put mainly from students at the University of New England (Bullock’s alma mater), and some from high school students. It flows more like a university economics tutorial than a conventional Q&A session.

Her speech and responses reveal that she is well across the detail and practical aspects of monetary policy, while her policy line is unwavering from the established dual mandate of the RBA – the need to bring down demand in the economy to suppress inflationary pressures, while ensuring that the economy does not enter a recession. It’s pretty well the established textbook Phillips-curve and NAIRU analytical framework.

Is it possible that she feels bound by the implicit oath of central bankers to abide by the sacred scriptures of economics, lest the RBA and by extension Australia’s other financial institutions are seen by the world to be apostate?

Financial Review journalist Phil Coorey questions her on this model, which assumes a certain homogeneity and fungibility in the labour force. What if the skills of our labour force are not matched to the needs of our economy; what if there is not one big “labour market”? If inflation results from a structural mismatch, then the crude one-big lever of monetary policy won’t work: it will simply exacerbate misery without suppressing inflation. Bullock sticks to the textbook model however, even though she shows, through her detailed knowledge, that she is well aware that Australia has a patchwork of labour markets.

Another question from a student challenges Bullock on the “goods” vs “services” model of inflation. That is, the idea that goods prices are determined on world markets, over which Australia has little control, while service price inflation relates to labour costs in Australia, over which monetary policy can have some effect. But as the questioner points out, while there is services inflation, it results from price rises in the finance sector, including insurance, which do not flow from labour costs. (Climate change is pushing up insurance costs, and other price rises in the finance sector relate mainly to high profits.)

One question that doesn’t get put is “How does the RBA compare the hardship resulting from a rising CPI with the hardship resulting from tight monetary policy?”. Another missing question is “Has the RBA assessed the risk to the Australian economy, if, as a result of its reluctance to reduce interest rates, the population elects a Coalition government?”.

That question may appear to be cheeky, but it’s a serious reminder that the extreme political movements in the 1930s were energized by popular reaction to the austerity policies of the time. Of course the Coalition isn’t proposing to go down the road taken by Nazis and fascists in the 1930s, but their economic policies would put Australia on a slow decline in prosperity, towards entrenched social division, akin to the path taken by South American countries last century. The Reserve Bank should not assume that its brief absolves it from considering the long-term economic consequences of its decisions.

Wages have stopped falling but they’re not rising

On Tuesday the ABS produced the Wage Price Index for the June Quarter. Alan Kohler, in his regular ABC news segment, explains that while nominal wages are rising, they are still barely keeping up with CPI inflation.

He notes that wages determined by awards have risen faster than wages negotiated in enterprise agreements, while wages negotiated in individual arrangements have fallen. That means that in the sector where wages are determined by the market, workers are in the weakest position. That does not support any idea that the labour market in Australia is overheated – one of the justifications for tight monetary policy.

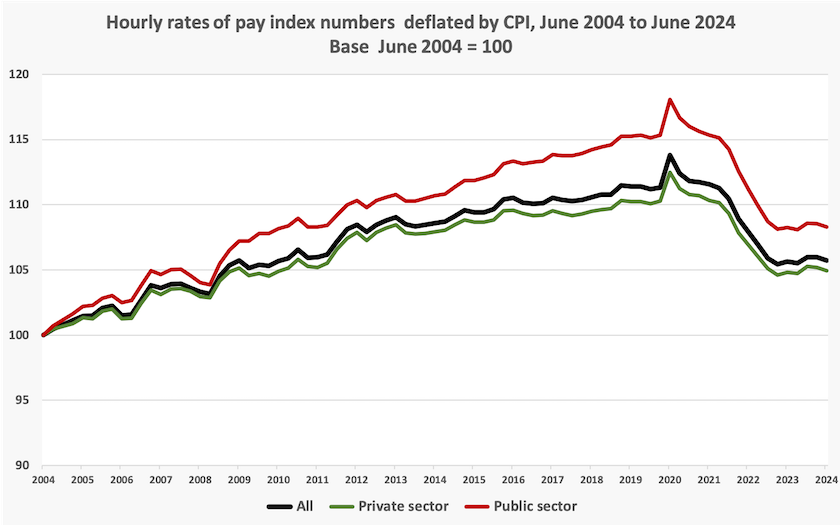

Presenting a longer-term view, the graph below, constructed from the same ABS wage price data and its CPI series, shows the movements in real wages (deflated by the CPI) over the last twenty years. We can see five distinct phases:

- strong wage growth from 2004 to around 2012;

- a distinct slowing in wage growth from 2012 to 2019 – a cumulative two percent over seven years – not much more than a rounding error;

- the jump during the pandemic – an uninformative artefact of the measurement technique, which is based on hours worked, which fell sharply;

- a sharp fall from late 2021 to early 2023;

- real wage stagnation over the last 18 months.

Real wages are now around five percent lower than they were in the immediate pre-pandemic level. Another way of looking at this is that they are now back to their level of around 2010.

One group who can expect to see a real wage rise in the near future are child care workers. Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin describes the government’s decision to lift the pay of child care workers by 15 percent. That’s a well-earned and overdue pay rise in view of the difficulty of their work and the responsibilities they bear: Why are child carers still paid less than retail workers? And how can we help fix it? He also provides a history of wages in the care sector, a sector dominated by women, whose work has been traditionally undervalued.

If some people’s real wages are rising, while on average real wages are stagnating, it’s close to a mathematical certainty that some people’s real wages are falling. Although the Reserve Bank is unlikely to admit it, a re-alignment of real wage levels is one of the benefits of inflation. A modest level of inflation allows for alignment, because nominal wages rarely fall in any industry or occupation. The pain of inflation is borne by those whose nominal wages cannot keep up with inflation, who perceive the cause of their hardship as rising prices rather than falling real wages.

It is possible that ten years of low inflation before the pandemic made it difficult for real wage reductions to occur. Those pent-up reductions may now be occurring.

On poverty traps and high effective marginal tax rates

The acronym EMTR (effective marginal tax rate) has become almost so common among economists that, like GDP or CPI, they often don’t bother to spell it out.

Most Australians working full time pay $0.30 tax for each extra dollar they earn. That comes from the 30 percent flat marginal tax rate for incomes between $45 000 and $135 000. To that is added a 2.0 percent Medicare levy for most taxpayers.

Those figures cover official taxes, but because we have a targeted social security system, as one’s income rises there can be a withdrawal of benefits, and extra unavoidable expenses. This withdrawal of benefits, combined with official taxes, is called one’s EMTR.

In some cases one’s EMTR can be greater than 100 percent. These situations are called “poverty traps”. Over the years there have been many stories of low-paid workers being confronted by a poverty trap when, for example, they plan to move from part-time employment to full-time employment, and lose a bunch of benefits. The people facing very high EMTRs or poverty traps are often women with child care costs.

A well-designed taxation and social security system will try to avoid poverty traps, because they discourage people from working, but perfection is elusive.

Ben Phillips of the ANU set out to discover how many people in Australia are confronted by poverty traps, and while they do exist, they are rare: The good news is most of us pay low effective tax rates on an extra day’s work, even including means tests and childcare he writes in The Conversation.

Not only does he find few instances of poverty traps; he also finds that two-thirds of people of working-age face an EMTR of less than 40 percent. Our established policy approach of means-tested benefits is working reasonably well in avoiding poverty traps.

Renewables in the bush

Sheep may safely graze

Hardly a day goes by when we don’t hear about another NIMBY movement in a rural region blocking a renewable energy project.

Often the protests are absurd. They’re about the aesthetic damage to landscapes already laid waste by a hundred years of clearing and overstocking, littered with derelict sheds and rusted farm implements. They’re about the noise of generators on windfarms, audible only with the help of a stethoscope. They’re about the loss of land occupied by solar panels, as if livestock are unable to graze in their shadow. And that’s before we get to fantastic ideas about windmills spreading deadly bacteria, or solar panels irradiating lambs with radioactive molecules that cause genetic modifications.

These movements, often organized by troublemakers on the far right, seek to open up rural versus urban divisions, and are aimed at stymying progress toward renewable energy targets.

In fact, according to the Regional Australia Institute, in its well-researched report Towards net zero: empowering regional communities, “there is general goodwill” towards Australia’s energy transition in rural regions. To quote:

Above all else, across the case study regions [regions in mainland states with renewable energy resources], communities saw the transition as an opportunity to build a lasting legacy for future generations.

They want to be involved, but not just as passive providers of land for projects. They want their own workforces to be involved with career opportunities: they don’t want FIFO projects. They want to share the rewards.

Regional communities saw the economic injection from the pipeline of renewables projects as an opportunity to enhance community liveability, expand local workforce capacity and augment community services.

For that to be achieved they seek “genuine collaboration on decision-making with government and industry”.

In terms of public policy they seek a six-point process to provide certainty and to guide a “just and equitable transition”. These are:

- Establishment of a Regional Prosperity Collective to match private investment in regions with place-based community needs.

- Development of a Local Legacy Fund, creating material community benefits for regions.

- Creation of a National Net Zero Framework to measure transition success, including a progress dashboard.

- Development of an Energy Transition Hub to enhance appropriate information flow.

- Equity in rate-based contribution from large scale renewable energy projects to support a just transition.

- Support for the establishment of an emissions trading scheme and a price on carbon.

This last one is unlikely to win over the National Party, but it’s a long time since they represented the interests of rural Australians.

Gaslit – how the fossil fuel industry achieved its social licence in Australia

Moomba South Australia

There is something strange about the gas industry in Australia.

The Australia Institute points out that although we are one of the world’s biggest gas exporters, alongside Qatar, we get very little economic benefit from these exports. The industry is largely foreign-owned, employs few people, and pays very little corporate tax in spite of the high world price of gas: Gas: the facts.

The ABC Ian Verrender pulls together some of the industry’s odd features. Although Australia is well-endowed with gas resources, we have allowed elevated global prices to determine our own domestic prices, driving inflation, largely because companies can circumvent domestic price caps. Even more oddly, while many gas export projects are going ahead, one large energy company is now building a gas import terminal in expectation of a world oversupply: Why the global fossil fuel sharks are circling Australia's gas export industry.

The Australia Institute and Verrender aren’t the first to point out these facts about the gas industry, but the question largely not addressed is how the industry came to have such a strong place in Australia. How did it come to exert so much political influence, and how did it get its social licence?

Journalist Royce Kurmelovs, author of Slick: Australia’s toxic relationship with Big Oil, explains the way the industry became so well established, in a 22-minute session on Late Night Live: Gaslit –what the gas industry knew about fossil fuels and global warming in Australia. In most of the world – USA, the Middle East – the fossil fuel industry was established long before there was much knowledge about its contribution to global warming, but by the time it came to Australia the science was well-established. Yet we have invited it in with open arms, even as its expansion clashes with our espoused aims on climate change.

Kurmelovs describes the public relations exercises by which the industry has gained that invitation. It’s much more sophisticated and strategic than the occasional generous campaign donation. Rather it has involved the establishment of think-tanks, and the clever use of methods of social persuasion – sophistry, bullshit (as philosophically defined), paltering (using selected truths to mislead) – everything short of outright lies. Because the industry does not have a long-term future, its strategy is now to lock in projects over the longest time possible.

That means, whatever we do in relation to domestic burning of fossil fuel, we will continue to make a hugely disproportionate contribution to global emissions. In its publication Australia’s global fossil fuel carbon footprint, Climate Analytics points out that with 0.3 percent of the world’s population, we are responsible for 4.5 percent of global fossil carbon dioxide emissions, with 80 percent of those emissions coming from our fossil fuel exports.

Writing in The Conversation Bill Hare of Murdoch University makes the same points in his article: Dug up in Australia, burned around the world – exporting fossil fuels undermines climate targets. The point he stresses is that we cannot simply separate out domestic emissions from emissions caused by others who buy and burn our fuel. That’s because a significant proportion of our domestic emissions are generated in the extraction of gas for export.

NAPLAN once again reveals wide inequities in school education

When ACARA (The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) produced the 2024 NAPLAN results for Years 3, 5, 7 and 9, some of the media reports gave the impression that these tests reveal a sudden deterioration in children’s results.

In fact, the report concludes, for all four years, with the same statement:

Nationally and across all states and territories, in all domains, the differences in average scores since 2023 were negligible.

Writing in The Conversation Sally Larsen of the University of New England suggests that there hasn’t been a longer-term decline either: Are the latest NAPLAN results really an “epic fail”?. One may get the impression of a decline from a quick look at the figures, but there has been a re-categorization of results, which tends to distort the gross figures.

The serious revelation in NAPLAN is confirmation that there are gross inequities in our school system. The NAPLAN results for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, from children living in the country, and from indigenous children, are particularly poor. We need to bring up the average by bringing up the most disadvantaged one third.

Jessica Holloway of Australian Catholic University, provides a similar explanation of NAPLAN, as well as some details of NAPLAN results, drawing attention to areas where results have improved: NAPLAN results again show 1 in 3 students don’t meet minimum standards. These kids need more support.

She also outlines the Commonwealth’s next funding agreement, for schools, involving an offer of $16 billion from the Commonwealth to the States, conditional on certain reforms being met. Details of the deal, including targets around improving the performance of the most disadvantaged, are in another Conversation article by Glenn Savage of the University of Melbourne: There’s a new 10-year plan for Australian schools. But will all states agree to sign on?.

Further explanation of NAPLAN results is in a post on the ABC website by Evan Young: NAPLAN results reveal one in three students not meeting basic literacy and numeracy expectations. He also describes issues around school funding, particularly funding of public schools.

The Commonwealth’s response is covered in a 13-minute interview with Commonwealth Education Minister Jason Clare: 1 in 3 students not meeting basic standards. He refers to a decline in the number of young people who complete high school: seven years ago 85 percent of students completed high school; now only 79 percent complete high school, and in public schools the decline is even worse – 83 percent down to 73 percent over the same period. This may seem to contradict the findings that there has not been a decline in NAPLAN test results, but Clare is talking about problems that go back much further, particularly early childhood learning. Reform has to focus on the years before children get to school, because it is extremely hard to catch up on early learning deficiencies.

Some of the interview is about Commonwealth-state funding issues, but on funding he asserts that the Commonwealth is making progress, albeit slowly, towards the Gonski recommendations of equality in government funding for government and non-government schools, which he hopes will see a reversal of the trend for parents to choose private schools.

He also fends off criticism from the opposition that the government is moving too slowly in implementing the funding agreement with the states, pointing out that it is hypocritical for the Coalition, with its dismal record in education funding, to criticize the government on this front.

In that interview he refers to the 2023 Productivity Commission Report on the National School Reform Agreement, which had specific recommendations for reform of schools, and to the 2023 Review to Inform a Better and Fairer Education System.