Media

How the media works – do you really want to know?

Eric Beecher, Chair and largest shareholder of Private Media (owners of Crikey) doesn’t call himself a media “mogul”, a term he reserves for a handful of very rich men who have the power to make prime ministers tremble. In fact, on the ABC’s Big Ideas program The men who killed the news, he describes himself as a media mongrel.

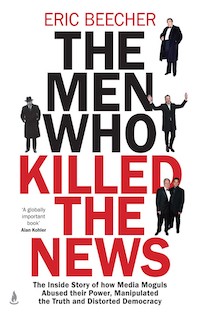

The session’s title is taken from Beecher’s book The men who killed the news: The inside story of how media moguls abused their power, manipulated the truth and distorted democracy.

He presents short biographies of several media moguls – good moguls and bad moguls – the distinction depending on the degree of editorial control exercised by the owners.

He enlightens us on the current court case in Nevada, where the 93-year old Rupert Murdoch is trying to change the family’s “irrevocable” trust, to ensure that control of the media businesses passes to his son Lachlan, rather than being shared among his four oldest children.

We might believe that this is about an ideological alignment between Rupert and Lachlan. There certainly seems to be a convergence of political views between the two, but the issue is also about who will run the empire so as to maximize profit. Editorial lines in Murdoch media are commercial as much as they are political. Detailed explanations of imagined conspiracies, stories of stolen elections, exposures of scientists developing vaccines with microscopic mind-reading microchips, the hoax of climate change – it all sells in a way that carefully-crafted fact-checked news doesn’t. And it’s all easy to write.

It’s a tough life for traditional media, who were once nurtured by the advertising “rivers of gold”. Others, upstream, are now drawing from those rivers.

Beecher says in order to survive, the media doesn’t have to follow the Murdoch model, however. There are media organizations, including The Guardian and The New York Times, surviving in this tough environment, while providing high-quality journalism.

He explains what’s happening in those rivers of gold. The traditional media have lost ground, first in their print editions and now in their on-line editions, while news-type feeds on social media have been growing. These are “news-type” because their content isn’t produced by professional journalists. In fact their stories are carefully-targeted as almost bespoke consumer products.

With the help of a little artificial intelligence, based on analysis of our internet searches, these feeds can be tailored to our identified tastes – or prejudices to use a less genteel term. We no longer get “the news” – something with at least a factual base even if it comes with a known bias – but “my news”. This is almost certainly contributing to political polarization.

The Big Ideas session with host Natasha Mitchell ends up with a discussion on the way media is funded. It’s unfortunate that there wasn’t time to cover funding in any depth, other than a general conclusion that there is a case for public funding of independent media, as is the case with the ABC, Canada’s CBC and Germany’s Deutsche Welle. The case rests on the public-good nature of news.

Funding is an important issue that shouldn’t be left to the tail end of a discussion. It is a truly weird arrangement that news should be a by-product of advertising. Beecher touches on this when he imagines publishing companies carrying commercial advertising in their books: we don’t accept that for books but we do accept it as a means to finance news.

Advertising is most effective when it is targeted at gullible people who are most easily parted from their cash: we shouldn’t be surprised that commercially successful media target the same audience.

The Big Ideas session is an hour long, including 10 minutes of Q&A. There is a short (13 minute) session with Beecher on Saturday Extra, but it covers only what most listeners would already know about the media, and it includes none of the stories about media moguls and mongrels. You have to turn to the Big Ideas session to learn about Randolph Hearst’s admiration of Hitler, and his editorialising to try to keep America out of the European war. Or to learn about how the Murdoch dynasty works.

Free-to-air TV and gambling

As it became apparent that the Commonwealth did not intend to implement a total ban on advertising for online gambling, as had been recommended by the Parliamentary Committee headed by the late Peta Murphy, many prominent Australians, including independent members of Parliament, have come forward urging the government not to yield to voices of self-interest opposing a ban. (See last week’s roundup for background on how gambling and media companies have been given privileged access to government ministers.)

It is now clear that the most strident voices opposing a ban are those of the media companies, rather than the gambling companies themselves. The gambling companies would certainly oppose a ban, but it’s convenient for them to sit back and let a more respected (or comparatively less disrespected) outfit put the case to allow advertising.

The situation is covered thoroughly in Mike Seccombe’s Saturday Paper article: The commercial broadcasters stalling gambling advertising reforms. In that article Anna Porter, professor of digital media and cultural studies at the University of Queensland, explains that the issue is about governments doing whatever it takes to save three commercial broadcasters, whose share of advertising revenue has been falling.

The Saturday Paper article is paywalled, but you can hear the commercial broadcasters’ case on a 10-minute ABC Breakfast interview with Bridget Fair of Free to Air TV Australia: Would free to air TV survive without gambling ads?.

There are some extravagant claims kicking around. The Guardian’s Paul Karp quotes Bill Shorten saying that some of the free-to-air commercial media need gambling advertisement revenue just to stay afloat. Such claims have led academics and others, drawing on data from the Australian Communications and Media Authority and other sources, to estimate the extent of that dependence. Andrew Hughes of ANU, writing in The Conversation, estimates that only 7 to 10 percent of their advertising revenue comes from gambling: Does free-to-air TV really need gambling ads to survive?.

It would be tough for the broadcasters to lose that revenue, but it would not be fatal, and as he points out, the original Murphy recommendations were for a phase-in period to give the broadcasters time to adjust.

More basically, Hughes presents the issue as one in industry adjustment. His conclusion is:

If free-to-air TV’s business model is so glacial it can’t function in the digital age, it probably doesn’t deserve to be operating in the big leagues.

Digital is here and has been for a while now. The media industry has borne the brunt of this change, but has also had the most time to adapt to the disruptors, who are now more established oligopolies and duopolies than “cool start-ups” out of Silicon Valley.

The argument that we need to protect sports gambling ads to protect the big media brands – has little to no basis. It’s a worn out argument we’ve seen time and time again – big tobacco, I’m looking at you.

Commercial TV is operating in a changing environment, one that has been disrupted not only by digital media, but also by basic technologies. Our sources of moving-picture information and entertainment have been subject to many changes over the years: free-to-air TV itself was the great disruptor in the 1960s. Now there is a great amount of moving-picture content on the internet. In fact so-called “smart TVs” are really Internet-connected computers, and operate as real TVs only if one has a functioning antenna. The free-to-air lobbies point to the cost of maintaining a transmission network, and the need to pay for access to the spectrum, but that market, with its high fixed cost, is fading away.

So the issue is, or should be, about maintaining the services now provided by free-to-air TV, while accepting that the broadcast technology itself may have a limited life. Some would say there would be no great loss if commercial television disappeared, but the government is adamant in its desire to see media diversity maintained

You can hear Bill Shorten present the government’s principles in the last 5 minutes of a 13-minute interview on ABC Breakfast. “Free-to-air media has an important role in a pluralist democracy”. He’s no lover of those companies that have maliciously used their voice to campaign against the Labor Party. Shorten was a victim of hyper-partisan media in his 2019 election bid. But he’s standing for a principle. If those commercial media go, their place won’t be taken by the ABC, The Guardian, The Saturday Paper, Crikey!, Michael West and other quality media guided by standards of professional journalism. It would be taken by the unmediated, unchecked flow of gut opinion, misinformation and disinformation on social media.

If this industry is to survive it needs some better source of finance than the profits of a costly and socially harmful industry – the proceeds of crime some would say. Annabel Crabb, in her post Why is the government tying gambling ads to the survival of TV? You know who really pays the cost puts it plainly:

We know who bears that cost. Families, employers, and children of gamblers who can't help themselves and whose losses account for a disproportionate share of the gambling giants' profits.

She calls it a “hypothecated tax on the disadvantaged”, implying, in line with sound economic principles, that if this industry is worth supporting, it would be better if it were funded through the public revenue system. (In fact, because of the fiscal demands imposed by gambling addiction, an advertising ban combined with public funding for journalism may be revenue-positive for governments.)

That’s the economic case. And the political case is that the government could present itself as acting with political toughness to protect the public, at a time when Dutton is cynically using the suffering of Palestinians to convey the message that the opposition has the political courage to make tough decisions.

Cinema paradiso

Dungog NSW

Contrary to expectations 70 years ago, cinemas survived the introduction of television. But the Covid pandemic was really tough on independent cinemas, particularly because most cinemas are in rented premises. (Why does so much of our small business sector have to endure feudal subservience to property owners?) Over the last three years, 100 cinemas have closed.

On the ABC’s Breakfast Patricia Karvelas discusses the future of cinemas with Michael Smith, owner of Sun Cinemas. There is a reasonably strong case for public support of cinemas, based on standard economic “multiplier” arguments: when cinemas bring people together to a town centre those patrons go on to support other businesses.

The more compelling case, which is difficult to frame in traditional economic terms, is that there are benefits in people getting up from their couches and going somewhere where they share an experience with other people.

And patrons can choose to turn up five minutes after the posted screen times to avoid advertisements.