Politics

Gendered violence – the power of entrenched ideas

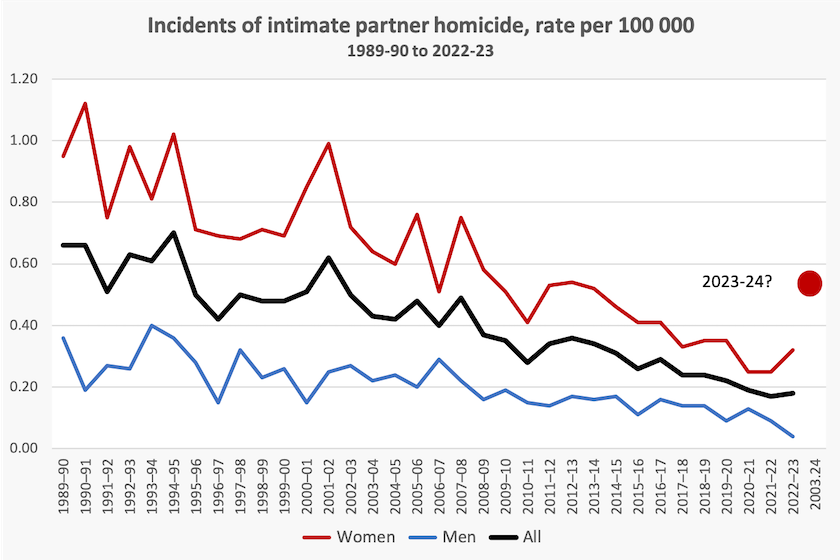

First the good news that is getting little attention. Over the last 35 years there has been a fall in intimate partner homicide. In 2024 a woman is far less likely to be murdered by her partner than she was in 1989, based on data collected by the Australian Institute of Criminology.

The bad news is that intimate partner homicide is on the rise again, shown in the graph below. The Institute noted with concern the increase in 2022-23. It will be some time before we have data for 2023-24 (imagine if we were so slow to generate GDP data), but based on figures used by knowledgeable people, and a back-of-the-envelope calculation, I have put a red dot in the area where the 2023-24 intimate partner homicide rate for women is likely to fall.

That’s serious, not only for the absolute number of murders (about 40 in the first 7 months of 2024), but also for the reversal of what until recently has been a successful trend. We could imagine the consternation for example, if there were to be a discernible break from the trend of improving airline safety.

Something has gone wrong: we don’t know what it is, and therefore we don’t know how to get back on trend.

Last weekend’s Saturday Paper carried a long article criticising the Commonwealth’s approach to domestic violence, an approach known as “primary prevention”. This is based on the liberal idea that the fundamental problem is gender inequality, and that if men can change their attitudes and behaviour to show respect for women, there will eventually be elimination of domestic violence.

The article – Health authority suppressed gendered violence research – is behind the paper’s paywall. A very condensed summary follows. In 2014 the Victorian government commissioned research into the causes of domestic violence. One of the chief researchers, criminologist Michael Salter, presented evidence showing that among the independent causal factors of domestic violence were alcohol and couples’ socio-economic status. The government in its report suppressed that evidence, focusing on the single aspect of attitudes and the need for behavioural change. That idea of “primary prevention” went on to form the basis of the Commonwealth’s approach to reducing domestic violence.

You can hear Salter explain the situation in an 8-minute ABC interview Why “primary prevention” isn’t stopping DV. He and his colleague Jess Hill also have a short paper on Substack Rethinking primary prevention. The issue isn’t just about the power of the alcohol industry or particular attitudes in the Victorian bureaucracy. Rather, it’s about attitudes and beliefs that go back to the nineteenth century. These are liberal beliefs about gender equality, but as the experience of Scandinavian countries confirms, gender equality, in itself, is not a sufficient condition to suppress alcohol-related domestic violence.

The independent contribution of alcohol to domestic violence is outlined in a further ABC interview with Philip Ripper of No to Violence: What role does alcohol play in gender-based violence? (8 minutes). Like Salter, he stresses that family violence has many causes: it is wrong to focus prevention on only one factor. He stresses that we need to appreciate the complexity of the factors contributing to domestic violence. To continue the aviation analogy, air-crash investigators almost always find a constellation of factors contributing to an accident.

A similar call for an approach to domestic violence based on all contributing factors is made by Sex Discrimination Commissioner Anna Cody on the Schwartz Media’s 7am podcast: The truth about men who kill women.

Maybe the reluctance to accept Salter’s research has been a fear that, in the way we seek to find single causes for this complex problem, we might revert to an all-out campaign against alcohol as the single driver of domestic violence. Such was the campaign by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in times past, who were campaigning for traditional roles for women and were seen as wowsers and killjoys.

We can see the issue in terms of the political power of alcohol companies, but the researchers go beyond such transactional explanations, pointing out that alcohol is so deeply embedded in our culture, in the way we see ourselves as Australians, that we seem to be reluctant to consider its independent contribution to violence.[1] The general point relevant to all public policy is that we can find evidence-based research too confronting when it rubs up against some of our entrenched beliefs and assumptions. Well-educated liberals are not immune from biases in their thinking.

1. I was once in a discussion with a senior Saudi Arabian public health official, who put to me the question “If your country had never had alcohol, would you legalize it? ↩

The reshuffle – it’s mainly about the stupidly-named Department of Home Affairs

There has been much political noise but little considered comment on the government’s ministerial reshuffle.

Bartholomew Stanford of Griffith University writes in The Conversation about Malarndirri McCarthy taking over from Linda Burney as Indigenous Affairs Minister. She faces an extremely difficult task, he writes, and that’s not just because she takes over from the experienced and well-respected Linda Burney.

Because she is from the Northern Territory – as is the opposition spokesperson Jacinta Nampijinpa Price – she will inevitability be involved in the Northern Territory’s elections, to be held in three weeks, on August 24.

Also, as confirmed in a recent Ipsos poll, public interest in indigenous issues, including closing-the-gap targets, has fallen since the defeat of the Voice referendum.

In her weekly session on Late Night Live, Laura Tingle discusses the reshuffle in the context of changes in the Home Affairs portfolio, including taking ASIO out of Home Affairs and putting it back under the Attorney General, where it has traditionally belonged.

Immigration is always a tough job for a minister, and Ministers Clare O’Neil and Andrew Giles have had a particularly difficult time having inherited the dysfunctional mess left by the previous government. The Department had too wide a remit and too little funding to administer the immigration program. Its corporate culture had been shaped by the Coalition’s hyped-up representation of Australia as a country under siege from immigrants with terrorist intentions. More recently it has been confronted with High Court rulings about detention of visa-holders with criminal records, which the media, including journalists who did not understand the separation of powers, presented as a government failure.

O’Neil and Giles have been working quietly to clean up the mess, including security vulnerabilities, that they inherited from Peter Dutton’s Home Affairs misadventure. One important initiative has been to introduce a new visa for temporary workers to protect them against visa cancellation when they report exploitative or abusive behaviour by their employers. This should help protect against underpaid indentured labour, a practice that was tolerated by the Coalition as an aspect of its policy objective to reduce wages.

The opposition’s malicious attacks on O’Neil and Giles have been yet another example of their disgusting behaviour. It habitually chooses to promulgate lies and scare campaigns, rather than to engage with policy issues when there are grounds to criticise the government. For example, there are serious questions about the government’s policies on student visas, but the opposition has chosen instead to mount a deceitful campaign about boat arrivals, and has made a stupid assertion about weakening security checks for immigrants from Gaza, as new Immigration Minister Tony Burke points out an interview about his new responsibilities (19 minutes).

Reaffirming multiculturalism – first get rid of the Department of Home Affairs

The government’s Multicultural Framework Review has received little public comment. Perhaps that’s because it’s about an area of public policy where Australia has done well, and there are no cases of corruption or severe maladministration exposed – just a set of 29 recommendations, mainly relating to institutional design and governance.

Its findings and recommendations are in a report Towards fairness: a multicultural Australia for all.

One recommendation that has passed largely unnoticed is #11: “Establish a Multicultural Affairs Commission and Commissioner, and standalone Department of Multicultural Affairs, Immigration and Citizenship, with a dedicated minister”. That would leave the Department of Home Affairs with only Customs and a stockpile of uniforms.

Andrew Jakubowicz of Sydney‘s University of Technology, writing in The Conversation, calls the recommended reforms “bold”, although most seem to be uncontentious.

One that has raised some interest is the suggestion, in Recommendation #3, which includes “an immediate review of the Australian citizenship test procedures, including considering providing the test in languages other than English and in alternative and more accessible formats”. That has caused some consternation in the usual quarters and has led to assurance by the government that we will stick to Oz English. The recommendation seems to be about assuring would-be immigrants that citizenship does not rest upon knowing Don Bradman’s score in the test match at Nottingham in 1938.

But on language it has some quite strong recommendations about the need for native Australians to learn languages other than English. Recommendation #19 reads: “The Department of Education and the Department of Home Affairs (through AMEP [Adult Migrant English Program]), in collaboration with state and territory governments, to increase investment for programs to support language acquisition courses at all learning levels, which is complementary to relevant curriculum cycles.”

Another recommendation that would reach the lives of all Australians is #21: “The Multicultural Australia Commissioner [a position to be established], together with the Department of Home Affairs Citizenship and Settlement sections, in consultation with the NIAA [National Indigenous Australians Agency] and across government as appropriate, to improve understanding of First Nations history in Australia as the first peoples. Develop initiatives to deepen Australia-wide understanding, such as the history presented through citizenship processes, civic participation, pathways to permanent residency, education and for older generations”.

These recommendations, in that they shape the culture experienced by native and immigrant Australians, are far-reaching. They may not be “bold” – they seems to be obvious for a country with a rich history – but over time they could change the way we see our country and its place in the world.

Gambling – why is the government indifferent to a serious problem?

Some have said that poker machines are to Australians what guns are to Americans. We have allowed a dangerous movement to grow so strongly that it has the resources to exercise huge political clout.

Odds of 649739:1

The ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods has just published two reports on gambling. The first provides figures and trends: Gambling participation in Australia 2024: Trends over time, and profiles associated with online gambling. The other, by the same authors (Aino Suomi, Markus Hahn, Nicholas Biddle) is about harm from gambling: Harm from someone else’s gambling: Affected others in the Australian population, 2024. Gambling is not a victimless crime. When gambling addiction wrecks a person’s life, others’ lives are affected, and the community has to pay for much of the damage through social security, health care and policing, while the thugs who run gambling businesses enjoy the profits.

Fortunately there is a long-term general downwards trend in gambling in Australia. By now 38 percent of the population can be classified as “non-gambling”, but there is a distinct gender difference: 55 percent of women but only 21 percent of men are so classified. Participation in gambling is negatively correlated with education attainment and with socio-economic status. On the other hand gambling participation is positively correlated with income. Unfortunately the statistics published by the ANU Centre do not differentiate enough between forms of gambling to let the reader determine trends. It is possible that the decline in gambling is associated with less participation in lotteries, masking growing trends in more costly and serious problems in addictive forms of gambling.

Covid-19 saw a reduction in gambling, particularly a reduction in use of gambling venues such as clubs. In the post-Covid era the recovery in gambling activity is largely in online modes, such as sports betting. Participation in risky gambling is now back to pre-Covid levels.

The researchers simply provide and summarise the data, but one clear implication is that gambling is shifting away from situations where there is some social context, where there are time-limited opportunities for gambling, and the need to make the effort to go out to a venue. These social and physical conditions have operated in venues such as racetracks as a means to keep in check some of the potential harm in gambling. Sports betting, now the most common form of online gambling, does not have these controls.

In the second study the researchers found that 5.8 percent of Australian adults reported being personally affected by someone else’s gambling in the past 12 months. Such indirect victims tend to be younger (18 to 24), earning a lower income, dealing with loneliness or psychological distress, and may have their own gambling problems.

That’s the hard data. The ABC’s Steve Cannane takes us to the mechanisms of the gambling industry in his post From behind bars, former sports betting addict Gavin Fineff is urging the PM to “tackle gambling addiction properly”.

Cannane reminds us that a parliamentary inquiry on online gambling presented last year, chaired by Labor MP Peta Murphy who has subsequently died of cancer, made 31 recommendations aimed at reining in gambling advertising, applying more stringent identity checks on gamblers and imposing a ban on online gambling inducements. But the government is yet to act on any of these recommendations.

He also tells the story of Gavin Fineff, a financial planner who stole $3.3 million from his clients to fund his sports gambling addiction. From jail he has written to the prime minister, urging the government to do more to regulate this industry.

While he is in jail Fineff shoud be away from the reach of sports betting companies, but the ABC Matt Eaton recounts the story of “Callum”, who has gone cold turkey and has not laid a bet for a year, but is still being hounded by Sportsbet.

Eaton reports that Tim Costello believes the government’s inaction on the Murphy report is explained by the government’s fear of taking on the TV broadcasters in an election year. Costello points out that "so much of Seven, Nine and Foxtel's TV advertising revenue comes from sports betting ads”.

It’s not only the Commonwealth that’s under pressure to rein in sports betting. Gambling experts in South Australia are urging their state government to regulate the industry, warning that the Olympic Games are offering a new opportunity for sports betting.

The parallels between America’s National Rifle Association and our own gambling lobby is clear. In both cases there is strong public support for reform, but politicians realize that those lobbies are so well-resourced that they could sway public opinion in response to any reform initiatives, and that they would be supported by opposition politicians unbound by any moral constraint, such has been the degeneration of the Republican and Liberal parties.

Barnaby the greenie

There has been a great deal of fuss about Barnaby Joyce’s vitriolic use of language. It’s certainly stupid and offensive, but it probably falls into the category of “microaggression”. In demanding his resignation the government risks confirming the idea that it is more concerned with issues of political correctness than with policy substance.

Sophie Vorrath of Renew Economy gets to the substantial issue: Joyce made those intemperate comments at a rally against a proposal to build a wind farm and battery in the New England Renewable Energy Development Zone, a project which the developer had been planning for three years.

No, there wern’t rainforests here

The anti-renewable campaign has been organized by an outfit calling itself “Rainforest Reserves”, Vorrath explains. The scientists at the University of New England would be truly amazed by the discovery of rainforest along ridge lines that have been cleared for agriculture.

The tactic of such campaigns is to pressure individual landholders to reject any approach from the developers, until they have enough refusals to render the proposed project unviable. It’s been successful in other regions, she points out.

This incident adds to the case for governments to use their power of eminent domain, the power they use to acquire property for roads, to override farmers’ protests.

It’s hard to see how that would be politically costly. The protesting farmers are probably hardened supporters of parties on the right. Those to gain from governments using their eminent domain powers would be more businesslike farmers, who would otherwise miss the opportunity to host a wind farm or solar array, local communities enjoying the benefits of higher income and employment, and the whole Australian community enjoying lower electricity prices.

More importantly it would counter the accusation that the government is gutless and insincere in its commitment to renewable energy. Just as Coalition governments gain kudos from taking on waterside or construction unions who are supposedly working against the national interest, Labor could benefit politically from taking on obstinate farmers standing in the way of lower electricity prices.