Ecoonomics

It’s not a “cost of living crisis”: it’s a deep problem in structural inequity

We keep on hearing about a “cost of living crisis”, as if we’re all doing it tough.

That’s not so. About two-thirds of Australians are coping quite well, while the other third are indeed having trouble making ends meet.

Ross Gittins puts it clearly in his post Cost-of-living crisis? Why only some of us are feeling the pinch, where he writes “some of us are doing it a lot tougher than others, and some of us are actually ahead on the deal”.

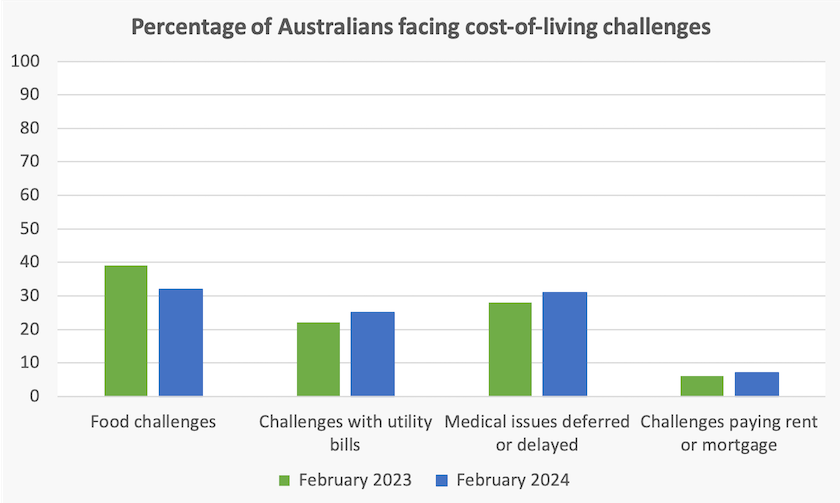

This imbalanced pattern of cost-of-living pressure is confirmed by the Melbourne Institute-Roy Morgan survey Taking the Pulse of the Nation, which looks at the proportion of Australians facing cost-of-living challenges, comparing responses in February last year with February this year.

The results covering four areas – food, utilities, health care and housing – are shown in the graph below. Notably the proportion of people experiencing food challenges is down from 39 percent to 32 percent. (This aligns with the latest ABS CPI release, which finds lowering food price inflation, apart from some items affected by adverse weather conditions.)

Other stresses have risen, reminding us that while inflation has fallen, it is still positive and for many, incomes have not kept up with inflation.

Some may be surprised that only 7 percent of people report that they are experiencing mortgage challenges, but those problems are concentrated among a small demographic group, typically younger people who have bought their first home in the last few years. Those who have given up the search for suitable accommodation and are couch-surfing or living with parents would not be facing bill stress. Therefore this figure provides a very incomplete picture of the extent of housing stress.

The ABC’s Michael Janda has a well-researched post demonstrating why most indicators tend to understate the hardship people face resulting from higher interest rates: Mortgage risks are rising but are they still understated by the RBA?. For example some people are free of mortgage stress because they have sold their properties, having borne the hardship of incurring transaction costs of buying and selling within a short period. He notes that the number of homes resold within 3 years has risen sharply since 2022.

The RBA, he says, focuses on the number of owner-occupiers who are in arrears in their mortgage payments as an indicator of mortgage stress. That indicator has been low and stable for a few years, but it doesn’t cover those who are making significant sacrifices in order to avoid going into arrears.

Even when we compensate for the understatement in that 7 percent figure, it is still clear that only a small proportion of Australians have been badly affected by high interest rates. As Gittins points out there is a sizeable proportion of the population with mortgages whose repayments have risen because of higher interest rates. But who hasn’t had the experience of juggling changing incomes and expenses? That’s not a “cost of living crisis”.

Unsurprisingly the Melbourne Institute-Roy Morgan survey finds that at least 60 percent of people facing cost-of-living challenges report symptoms of mental illness – feeling depressed or anxious “all of the time, most of the time or some of the time”. That compares with 26 percent or less among those without challenges.

The $3000 test

As an indicator of precarity the survey looks at people’s capacity to meet a requirement to come up with $3000 within a month to cover an unexpected expense. That may be emergency car or house repairs or travel because of a family tragedy. Almost all of those two-thirds without challenges have access to liquid resources, but others are far less resilient. The people most seriously short of cash are those finding it difficult to pay rent or a mortgage, suggesting their sources are close to maxed out.

The ABC’s Hanan Dervisevic draws on the Melbourne Institute-Roy Morgan survey, and data on the fall in household savings, to write about the way people can develop an emergency fund: How much should you have saved in an emergency fund? Experts say the key is to start small. Financial advisers, she points out, suggest people should have three to six months of take-home pay in such a fund.

She doesn’t go further into the benefits of people having a cash or near-cash reserve, but they can be considerable. People with such a buffer can do without credit cards and buy-now-pay-later schemes, using debit cards instead. They can take advantage of substantial discounts in house and car insurance by choosing policies with high deductibles. In general, those with liquidity have the means to free themselves from subsidising a bloated high-cost finance sector.

It's about an unfair and enfeebled tax system

The main finding in the Taking the Pulse of the Nation report is that there is something very wrong with the distribution of wealth, income and opportunity. There has been an extraordinary failure when a third of people are reporting food challenges in a country so naturally bountiful as Australia. Similarly it is disgraceful that a third of people should be deferring or delaying medical procedures.

The easy and partisan response is to blame the Albanese government, as if these problems have arisen because of policy failures over the last two years. But the problems are more entrenched. People’s difficulties in buying food result, in part, from high-cost practices within the food industry, including excess packaging and advertising.

They also result from failures of successive governments, mainly Coalition governments, to attend to economic reform. Weak competition policy has contributed to high food prices, successive cuts to Medicare have contributed to challenges in meeting health costs, privatization of electricity authorities and a failure to invest adequately in renewable energy have contributed to high utility costs, and severe cuts in public housing have contributed to housing stress.

The cost of these failures is concentrated unfairly on a third of Australians. Once we see it that way, rather than as a “cost-of-living crisis” that implies a shared burden, we have to face the uncomfortable fact that its solution involves spreading the cost more fairly, particularly by having the well-off pay more tax.

If the Albanese government is to shoulder some of the blame for this situation it’s for having done too little to repair the damage it inherited from the Coalition, particularly our weakened public revenue base. But the Coalition has absolutely no intention of getting the privileged to pay more tax, and politically they are very satisfied when journalists keep referring to a “cost-of-living” crisis.

Consumer prices – why the Reserve Bank can take a break

The ABS released the much-awaited Consumer Price Index on Wednesday. The headline figure is that between June last year and June this year, prices in the ABS basket of goods rose by 3.8 percent.

Many journalists simply state that this means inflation is 3.8 percent, as if the ABS is able to make an unambiguous statement about inflation. But that is a gross and misleading simplification and an overstatement, for at least three reasons:

- The CPI is a measure of movements in selected consumer prices. It is only one of a number of inflation indicators, and it has an unavoidable bias in overstating the impact of increasing prices.

- That 3.8 percent is a historical figure. It tells us how the CPI moved between June last year and June this year. The movement in consumer prices now may be higher or lower.

- It includes some once-off movements that do not necessarily persist.

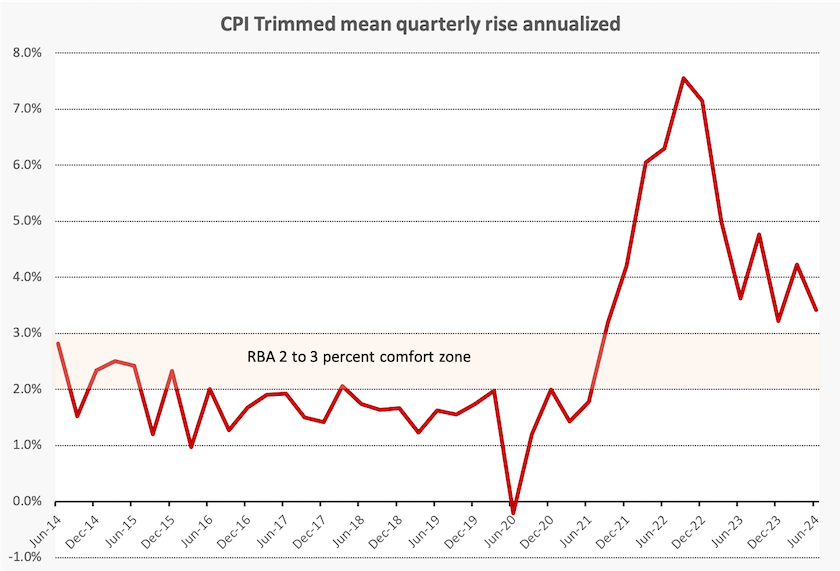

Therefore, making the best of data provided by the ABS, I have estimated that inflation now is about 3.4 percent, using only the final three months of data, mathematically converted to an annualized estimate, and the ABS trimmed mean series, which the ABS says “provides a view of underlying inflation by reducing the effect of irregular or temporary price changes that can impact the CPI”. That’s all statistically kosher. This movement is shown in the graph below, indicating that inflation is still on the way down from the high levels in the last days of the Coalition government, and is well on the way towards meeting the RBA’s two-to-three percent comfort zone.[1]

There may be some alarm at the ABS finding that the rise in the services component of the CPI is higher than the rise in the goods component, and that the rise in the non-tradeable component is higher than the rise in the tradeable component. Both suggest that we may simply be enjoying lower import prices, while there is still home-grown high wage-induced inflation.

A little digging into the detail about service price rises provided by the ABS dispels this concern. Insurance prices are still rising steeply – a rise that can be traced to the effects of climate change (as pointed out by the Productivity Commission). Rental prices are still rising – an effect driven in part by higher interest rates. Private health insurance premiums are up, which is an annual once-off event with regulated rises occurring in the June quarter. There is no hint of a wage effect in these movements.

In terms of what is important to those concerned with the cost of living, the price of what the ABS calls “non-discretionary items” rose by only 2.8 percent over the last year. This is an overstatement because the ABS includes private health insurance as “non-discretionary”, although for most people it is simply a waste of money.

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, believes the RBA is unlikely to raise rates when it meets next week (Tuesday August 6). He wrote his article before the ABS produced its report, but his guess about the headline rate was spot on. He points out that many prices are “administered’. That is, they are subject not only to market forces but also to government decisions. For example the price of tobacco rose by 3.0 percent over last year and that’s to do with excise rates. Also the trend internationally is for inflation to be falling and there is no reason we should be out of step.

The ABC’s Ian Verrender, also writing before the ABS announcement, came to the same conclusion: Why the Reserve Bank of Australia should hold off on interest rate hikes in August. His arguments rely not only on a dissection of CPI data, but also on the economic headwinds facing the Australian economy.

1. There is also a trimmed mean chart on the ABS website, which looks a little different from the one I have generated. That’s because the ABS chart shows the annual movement (i.e. 12 month lagging), while I have presented the annualized movement (one quarter compounded). The underlying message of reducing CPI inflation is similar. The ABS states “This is the sixth quarter in a row of lower annual trimmed mean inflation, down from the peak of 6.8 per cent in the December 2022 quarter”. Treasurer Chalmers has been feasting on that statement. ↩

Have the rumours of Rex Airlines’ death been greatly exaggerated?

The probability of Rex’s survival is explored in a Conversation contribution by Justin Wastnage of Griffith University: Rex Airlines’ future up in the air amid questions about viability of small airlines in Australia.

He goes through problems shared by many airlines, including their high-risk financial structure, based on leasing rather than owning aircraft. (Rex owns its small planes but has leased its Boeing 737s.) He also describes the particular problems faced by Rex in securing aircraft suitable for its non-capital city routes: there is a worldwide shortage of medium-sized turboprop aircraft suited to such purposes.

He believes that there is a great deal of political support for Rex, and that it has a future. The government seems to be committed to ensuring that Rex can continue with its non-capital city services.

The shadow minister Bridget McKenzie, in a 7-minute conversation on ABC Breakfast, suggests that the only airline with friends among the current government is Qantas: Rex failure would be “catastrophic”. That’s an unjustified simplification of the situation.

Not covered in the debate so far is the burden placed on airlines, particularly country airlines, by privatization and over-the-top security requirements. Airports in inland and coastal cities were once owned by local governments, who operated them as utilities, charging low or zero landing fees as a means of attracting traffic and serving ratepayers. But that has given way to privatization, each airport being effectively a regional monopoly, inflicting on the community all the costs of monopolization including expensive landing fees.

Sole survivor

Then there have been absurd security regulations, such as one requiring small passenger aircraft to be fitted with reinforced secure cockpit doors. Because of weight limitations that requires the sacrifice of one or two passenger seats. It’s as if Al Qaeda is plotting to hijack a Beechcraft King Air and crash it into the Mildura town hall.

Our security agencies are never called on to justify their interventions on cost-benefit-risk grounds. There is solid research confirming that security-induced rises in airfares, because they have resulted in more people choosing to travel by car, have caused far more deaths than those security measures have avoided.

No one seems to be ready to criticize the government for its dogged adherence to established practices which have seen successive airlines fail to break the capital city duopoly, and which have seen the persistence of absurdly high airfares between medium-sized cities. We could criticize Minister Catherine King for being slow to attend to these problems, but Coalition governments have not even tried.

Successive transport ministers, Coalition and Labor, have seen airlines in isolation. Similarly they have seen passenger rail in isolation. If they could consider passenger transport in system terms they would be amenable to seeing high-speed passenger rail along the Brisbane-Sydney-Canberra-Melbourne-Adelaide corridor as a competitive alternative to air transport, in the same way that European countries recognize the interrelationships between transport modes. An up-to-date rail alternative would go a long way to keeping the airlines and the airport owners in check.

An intercapital rail system would still not serve Bunbury, Bourke or Broken Hill, but in view of the clearly demonstrated failure of private companies to serve these markets at a reasonable price, why should the Commonwealth not operate non-capital city air services as a government-owned utility? We don’t baulk at the idea of using our taxes to provide lightly-trafficked roads, small schools and small hospitals in our non-metropolitan regions – all sub-economic in a hard-nosed sense. What do we have against a publicly-owned airline as a service to the seven million Australians about whose welfare Bridget McKenzie and many others are concerned?