Other economics

The Los Angelisation of Australia: we need a clearer way to think about “regions”

You may have read that Metro millennials are fleeing Aussie cities in colossal numbers, to report a Domainarticle published last week, or have heard a short ABC segment Millennials moving to regions “in droves”.

From these sources one may get the impression that “millennials” (aged 28 to 43) are heading out of the cities to escape a deadly plague, reminiscent of Boccaccio’s Decameron, or that Australians are moving against the global tide of urbanisation.

But it’s not like that. There are people moving out of our capital big cities, particularly Sydney, but most of them are moving to other capital cities. Among those moving, however, there is a net residual group who move out of capital cities to what are called “regions” – i.e. Australia outside our capital cities.

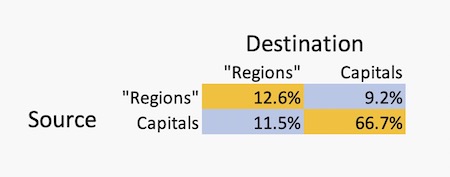

The source behind these articles is the latest (March quarter 2024) edition of the Commonwealth Bank Regional Movers Index, from which I have copied the pattern of movement in a small 2 X 2 matrix below (known in the trade as a “transition matrix” index).

This presents a picture of 100 people who moved in that quarter. Of them 67 moved from one capital to another; and 13 moved from one “region” to another. Of the other 20 movers 9 went from “regions” to capitals – our long-established movement – but their movement was more than offset by 11 people who moved in the opposite direction.

It is not a Decameron - type escape from plague and pestilence, although it does have some connection with the Covid-19 pandemic, because that prompted many people to head out of the capitals and the movement is continuing at a slower pace, as the report shows. It has also been driven by opportunities to work from home and high house prices in capital cities.

They’re not coming here (Farina)

More importantly it’s not a “flight” from the cities. It’s simply a movement out of the dense capitals. The destinations are mainly within 150 km of the capital cities, according to the Regional Australia Institute. The Gold Coast, the Sunshine Coast, Geelong, and Moorabool (between Melbourne and Ballarat) are the top destinations.

Perhaps what we’re witnessing is the development of massive conurbations, spreading out from our already-huge cities. Geography may save Sydney and Hobart, but other capital cities, with abundant land for subdivision and coastal strips, are all subject to the same sprawl.

Identification of this as a movement from our cities stems from an established but dysfunctional way journalists and many policymakers use the classification “regional”. If you don’t live in a state capital city or in Canberra, you live in a “region” – a term that covers everywhere else from Wollongong to Warooka (look it up).

It’s not a useful classification, because it ignores the distinct regions within our capital cities, and because it ignores the fact that we now have many large and growing cities outside our state capitals, in which life has more in common with life in state capitals than life in country towns.

At the same time there are ongoing problems in our inland settlements – aging populations with limited access to health care, poverty and its attendant problems, concentrated areas of youth crime, poor transport connections, high prices and many other disparities with our urban regions. These are generally different from the problems in the extended outskirts of our big capitals, also described as “regions”.

We should purge this “regional”/capital city classification from our way of thinking: it’s getting in the way of good public policy.

The stupidity (or criminality?) of privatization

If you live in Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane, you are familiar with the curse of toll roads. Because they are used by car-dependent workers who travel long distances, while the well-off generally live in urban regions well-served by public transport, they are unfair. And because there are often alternative non-tolled routes there is extensive rat-running. This means there is still congested traffic, particularly truck traffic, on city roads, thwarting any possibility of taming city roads to make them more community-friendly, while for much of the time the toll roads remain under-utilized. (This is an example of what economists call “deadweight loss” – the main cost of monopolization.)

Toll roads are the most visibly stupid outcome of what Ross Gittins calls unthinking privatization, which has left us a mess to be cleaned up.

Gittins specifically explains the economic distortion of Sydney toll roads, and the partial reforms recommended by Allan Fels and David Cousins, whose capacity to suggest reforms has been constrained by toll road contracts that hold up to 2060.

Airports too

Toll roads are just one economically distortionary outcome of an obsession with privatization that have gripped governments, mainly Coalition governments, since around 1990. Airports, electricity transmission lines, and shipping ports are among natural monopolies that should have been kept in public ownership, but because they were privatized we are paying too much for airfares, electricity and for all goods that pass through our ports.

Privatization of assets was driven by the cosmetics of public finance. When assets are sold there is a boost to the government’s cash flow, most of which may show up as “revenue” if the asset had a low valuation, but that’s just an accounting peculiarity. Governments claim that privatization as a means to fund new or expanded assets is a way to avoid government debt, but whether it’s through public or private borrowing, the funds have to be raised, and as Gittins points out, the cost of financing private capital is higher than the cost of financing public capital.

More basically, as the toll road example shows, the objective of a private owner is to make profit, while the government as owner can ensure that the system is managed in the way that maximizes the performance of the whole system, even if parts of the system are unprofitable. Proponents of privatization claim that objectives to maximize community value can be built into regulations associated with privatization, but companies game regulatory systems, regulations do not cater for changing needs, and once the owner of a privatized asset has banked enough profit they have the resources to mount expensive legal challenges against regulators proposing anything that would diminish owners’ profits.

Australia has ranked alongside the UK as one of the countries most given to privatization. In that country the newly-elected Labour government is pushing ahead with plans to re-nationalize railroads, a decision which has strong popular support. Apart from a partial re-entry into electricity supply by the Victorian government, our state and federal Labor governments have been reluctant to push against privatization, presumably because Liberal Party politicians, drawing on the public’s ignorance of economics and accounting, would run scare campaigns about government debt.

Gittins is right: governments can borrow at lower cost than private companies, and they have more capacity to absorb risk. But has privatization been “unthinking” as he claims? There is plenty of evidence that Coalition governments have been weak economic managers, relying more on gut feeling rather than a reasoned consideration of market failures, which should guide the distinction between public and private provision.

Or perhaps Coalition politicians are not really as stupid as we may be led to believe by their public statements. Maybe they perfectly understand the economics of monopolies and privatization, and have been engaged in Putinesque-style kleptocracy, handing over public assets to their mates.

If that’s the case state governments would be within their rights to tear up those contracts stretching out to 2060. They could compensate the toll-road companies on the basis of the written-down value of their assets, rather than the present value of their expected profits, in the same way as governments can legally confiscate the benefits of criminal transactions.

Or do we go for the explanation that Coalition politicians are simply stupid when it comes to economic management?

Measuring what matters

In prosperous countries including Australia, proportions of the population feel they have been left behind. The discontent is hard to define, and it’s not necessarily related to economic conditions, because it has grown while people’s welfare as indicated by established economic indicators has improved.

In a broad sense this is understandable, in terms of established theory such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: as our basic material needs are satisfied we seek fulfilment in higher-order needs. So it is reasonable that governments should seek to monitor society’s wellbeing in ways that go beyond traditional economic metrics. If people feel that they are left behind, it makes sense that we should be looking at social inclusion with the same rigour as we look at inflation or the unemployment rate.

To this end, from early this century, the ABS was developing other indicators of wellbeing. In 2013 it launched the first Measures of Australia’s Progress statement, covering four broad domains – society, economy, environment, governance – broken down into 26 sub-categories. As examples these included “safety”, perceptions of “a fair go”, “economic opportunities”, “trust”, “informed public debate” and so on.

The Abbot government killed the project, and much expertise was lost as the team of experts the ABS had assembled moved to other employers, some in other countries pursuing similar initiatives. The Albanese government has developed a similar initiative, Measuring what matters, aimed at achieving “inclusion”, “fairness” and “equality”, covering five broad areas described by adjectives – “healthy”, “secure”, “sustainable”, “cohesive”, “prosperous”.

To the cynic these may seem to be inconsequential exercises, but they have involved a large amount of public consultation and design, because in a democracy a government has to ascertain and respect the different values held by different members of the community. There has been no attempt to consolidate indicators into a single indicator (akin to GDP), because that would involve assigning weights to different aspects.

Also, these exercises take time to produce meaningful information in terms of time series. A single snapshot statistic, such as the physical assault victimisation rate (one used in the ABS MAP project), tells us little until it is developed in a time series exposing trends. That’s why the discontinuation of the ABS MAP initiative, before those series were developed, was so wasteful.

The Albanese government announced Measuring what matters with a flourish when it brought down its first budget, but the project seems to have gone quiet. That’s understandable, because the whole project has to be re-developed.

The Murdoch media and Angus Taylor have been dismissive about Measuring what matters: in their characteristic short-term view they assert that the government should be concerned only with immediate cost-of- living indicators. Or is it that they have some problem with inclusion, fairness and equality?

Writing in The Conversation Warwick Smith of the University of Melbourne brings us up to date on the Measuring what matters initiative.: Despite what you’ve read, Jim Chalmers’ wellbeing framework hasn’t been shelved – if anything, it’s been strengthened. It’s alive and well, and has been moved from Treasury to the ABS, where it will be treated with the same rigour and care as the previous MAP initiative. As Warwick Smith writes:

The idea that we shouldn’t be thinking about broader measures of progress because we need to concentrate on what’s in front of us impoverishes our view of what’s possible.

How far should the state support philanthropy?

The Productivity Commission has tabled the final report of its inquiry into philanthropy in Australia: Future foundations for giving.

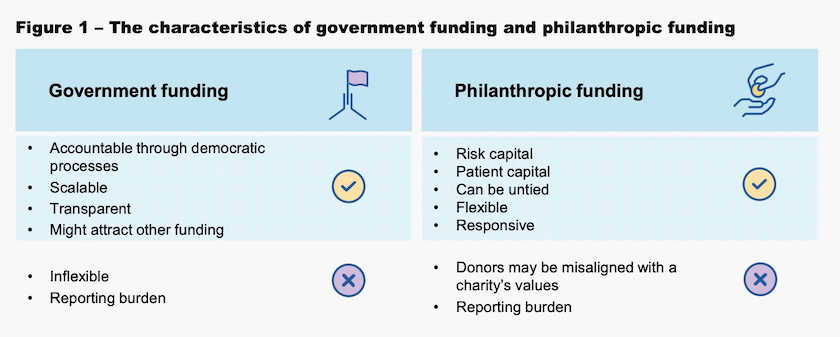

Its treatment of philanthropy is pretty much in line with mainstream economic theory, summarised in a diagram copied below.

In line with these costs and benefits it reviews the Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) system, which determines the charities that are eligible to receive tax-deductible status and recommends it be overhauled.

It found that:

… the arrangements that determine which entities can access DGR status are poorly designed, overly complex and have no coherent policy rationale. This creates inefficient, inconsistent and unfair outcomes for charities, donors and the community.

Its main recommendation, overlooked by most media, is an expansion of the number of charities eligible for DGR status, particularly those focused on advocacy and prevention of harm. In terms of government revenue forgone this would not be expensive, because most of these charities are small, and rely heavily on the contributions of volunteers.

The recommendation that has commanded most attention, however, is that DGR status be withdrawn from school building funds. Writing in The Conversation Matthew Wade of La Trobe University explains how this recommendation has resulted in a backlash from the private school lobby: The Productivity Commission wants to axe a key tax break for private school donations – but the government is determined to keep it.

Expect to see more fine stadiums, theatres, gymnasiums and libraries in private schools, while our public schools make do with demountable classrooms.

Paying for exam results

Recently The Economist ran a leader and a set of articles ”How to raise the world’s IQ”. For poor countries the best returns are in increasing kids’ nutrition. In rich countries, which have seen falling scores in PISA math, reading and science scores, the answer seems to be in lifting the performance of schools, adopting practices demonstrated to be successful in prosperous Asian countries.

Jayanta Sarkar and Dipanwita Sarkar of the Queensland University of Technology have found another way to lift scores on standard tests: offer students a financial reward for a good test result. Their article What happens when you pay Year 7 students to do better on NAPLAN? We found out is published in The Conversation.

They explain their well-controlled experiment. It was to see whether students were trying as hard as they could in these tests. The rewards on offer (up to a maximum of $20) were announced just before the test, so as to remove any incentive to study for the tests. The intention was to see how the rewards affected their test performance.

The students were in public high schools in southeast Queensland, and they came mostly from socio-educationally disadvantaged backgrounds.

The rewards worked in lifting test scores, leading the experimenters to conclude that many students in these schools were normally not putting as much effort as they could into these tests. That was the crucial finding, rather than a replication of established work on motivation and reward. It was certainly not directed at any policy suggestion for financial rewards for test performance.

The most compelling suggestion is that these students just don’t see the point in the tests. Maybe it’s about the tests themselves, or maybe it’s a belief that no matter how hard they try, there are no beneficial consequences. Either way the findings hint at failures in the education system, resulting in students’ capabilities being under-developed.

Perhaps if they had conducted this experiment with students from a more advantaged background they wouldn’t have been so effective, because those students would be more aware of the benefits of high test results. That would be a useful hypothesis to test.