Australia’s energy transformation

Hydrogen economics

There was glee among the anti-renewables mob when Andrew Forrest announced that Fortescue was deferring its green hydrogen plans. Some journalists, who must have goofed off in their high school physics classes, seem to have confused green hydrogen plans with Australia’s plan to achieve 82 percent renewable electricity generation by 2030.

Both plans are consistent with the broader Future made in Australia policy, both are directed at reducing CO2 emissions, and both are based on maximizing the economic opportunity from Australia’s extraordinary renewable resources, but there are fundamental differences.

Developing a renewable-based electricity grid is based on commercially-established low-cost technologies – wind and solar power.

Large-scale production and use of hydrogen as a means to de-carbonise, is on a different track. It’s a proven technology – as a substitute for coal to reduce iron ore in the steel-making process, in the production of alumina, in the production of ammonia (the basis of nitrogenous-fertilizers), and in the production of explosives – but all are commercially dependent on getting the price of producing hydrogen to competitive levels.

Writing on the ABC’s website Ian Verrender describes the commercial reasons behind Fortescue’s decision. It’s largely a question of the best application of the company’s resources. For now, the best returns for the company’s renewables programs is to concentrate on producing electricity from renewable sources.

Another reason why the development of green hydrogen is pushed back is that it is in direct competition with other green technologies. There were once ideas that hydrogen could replace natural gas for household heating and cooking, but the pipeline infrastructure is not up to the task, because the hydrogen molecule is much smaller than the methane molecule, which means there would be too much leakage. It’s better for households to turn to electrification. There are hydrogen fuel-cell cars on the market, a few hydrogen-powered buses run by transport authorities, but it appears that for transport hydrogen’s commercial viability will be mainly for large trucks.

If you have 12 minutes to spare you can hear an interview with Tony Wood of the Grattan Institute and Sam Crafter of South Australia’s Office of Hydrogen Power, on Australia’s hydrogen future, on the ABC’s Saturday Extra. Fortescue is not the only business in green hydrogen, and in any event the company is still going ahead with several hydrogen projects. Crafter describes South Australia’s existing projects and plans, including the state’s Green iron and steel strategy, which will involve a complete change in processes at the established Whyalla steelworks. He also mentions that the state is going ahead with a hydrogen hub at Port Bonython, one of seven hydrogen hubs being developed around the nation.

Writing in The Conversation – Fortescue has put its ambitious green hydrogen target on hold – but Australia should keep powering ahead – Kylie Turner and Luke Brown put the economic case for hydrogen. At this stage the industry is subsidised by government, subsidies being justified in terms of risk-sharing in a new industry in a rapidly changing market. A subsidy is a second-best approach in the absence of a carbon tax, which would force companies using fossil-fuel based technologies for making hydrogen to include the cost of their contribution to climate change in their pricing.

Renewable-generated hydrogen is going ahead. Fortescue’s biggest projects are pushed out a few years, but these delays are minor in comparison with the time to get nuclear power up and running, and the trajectory of cost competitiveness is on the side of renewable energy technologies in a way that it isn’t for nuclear energy.

The Coalition’s nuclear power idea is based on an obsolete model of electricity supply

Circulating in the media are three arguments against nuclear power in Australia. One is based on safety, an emotive issue, involving unresolved questions about future costs, and the dangers are probably overstated. The danger issue doesn’t need to be argued, however, because the main problems with the Coalition’s nuclear power plans have to do with cost and the long time before the first kWh would be generated.

Those impediments were confirmed in a speech earlier this month by AEMO CEO Daniel Westerman: Australia’s energy transition: What’s needed to keep the momentum going. He said:

Our ISP [Integrated System Plan] does not model nuclear power because it is not permitted by Australian law, and development of nuclear power generation is not a policy of any government. But we know from our work with the CSIRO on the GenCost report that nuclear is comparatively expensive, and has a long lead time. Even on the most optimistic outlook, nuclear power won’t be ready in time for the exit of Australia’s coal-fired power stations.

The Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering has just released an assessment of the viability of small modular nuclear reactors, which feature strongly in the Coalition’s proposals. These reactors are still at an early development stage: it will be many years before they become established. Although the study does not explicitly address costs, it does point out that early adopters are likely to face much higher costs than those who wait for SMRs s to become a mature product. As ATSE President Katherine Woodthorpe explains on ABC Breakfast, small modular reactors are unlikely to become a realistic energy source in Australia for decades, and our large coal-fired generators are closing in the next few years.

Writing in The Conversation Asma Aziz of Edith Cowan University reminds us of another cost component not covered in the Coalition’s plans: Without a massive grid upgrade, the Coalition’s nuclear plan faces a high-voltage hurdle. The Coalition’s idea is about replacing retiring coal-fired generators with nuclear plants, plugged into the existing transmission infrastructure. But as she points out, demand for electricity is growing rapidly, which means the cost of upgrading the transmission network should be included in the Coalition’s plans. (It is already included in the costings for renewable energy.) The other point she stresses is that all power plants, whatever their technologies, are subject to outages, planned and unplanned. A distributed set of comparatively small solar and wind plants therefore need less transmission redundancy than large centralized nuclear plants.

There is a fourth, and more basic problem with the Coalition’s nuclear proposal. It’s based on an old and inflexible “base load” model, which was determined by the technology of coal-fired generation. There has to be enough capacity in the system to cope with demand peaks, and that was achieved by keeping the boilers hot, keeping the generators spinning, and shovelling in heaps of coal as demand rose. Nuclear is a little different, in that shovels aren’t involved, but the principle is the same.

There are now more flexible and lower-cost ways to meet peaks.

Maybe nuclear power could be supplemented with peaking gas capacity – as is envisaged for renewable systems – but if there is a large nuclear base-load capacity, renewables would be a bloody nuisance. This is illustrated in a Conversation article by Bill Grace of the University of Western Australia: No room for nuclear power, unless the Coalition switches off your solar. Nuclear power plants are expensive to build, and as he says “the only way to make nuclear power work in Australia is to switch off cheap renewable energy”.

Under the AEMO Integrated System Plan, there is no fixed “base load”. With a geographic distribution of renewable sources (including some well to the west where the sun still shines while it is setting on the east coast), there will be enough electricity to meet our needs. That pattern of supply, however, won’t meet our hour-by-hour needs, which is why some type of storage is needed – batteries to meet instant short-term demand, pumped hydro to meet demand over a few hours.

Think of those storage facilities as a bank account into which you make big deposits and withdraw in many small transactions. For reliability there will be peaking generators – natural gas for some time, and in the future green hydrogen as pipelines and burners in power plants are replaced. This is not hypothetical: it’s the way South Australia is heading as Bill Grace explains. It’s the way that state will be operating in a few years’ time, as Rosemary Barnes, of Pardalote Consulting explains in a 12-minute discussion on Radio National: South Australia's ambition to reach 100% net renewables.

Battery technology is pushing ahead quickly, lowering the cost per kWh to store electricity. In the last ten years that cost has fallen from $US780 to $US139 for lithium-ion batteries. Maybe the future will not see such a rapid cost reduction for lithium-ion batteries, but we are now seeing the development of sodium-ion batteries, which rely on much more plentiful materials than lithium and cobalt, crucial ingredients in lithium-ion batteries, as Peter Newman explains in The Conversation: Sodium-ion batteries are set to spark a renewable energy revolution – and Australia must be ready. They are cheaper than lithium-ion batteries, but they have a lower energy density. That means per kWh stored they are heavier, which would rule them out, for now, for applications such as cars and light trucks. But they should be ideal for stationary storage to firm renewable-sourced electricity.

All the above is in the context of a debate about the comparative cost of nuclear energy and renewables. The Australian community is being distracted from that debate, because the Murdoch media and Coalition-aligned think tanks are spreading absurd misinformation and disinformation about the cost of renewable energy. They’re hard to take seriously: they’re in the same category of idiocy as Putin’s claim that Ukrainian Jewish Nazis are waging a war of aggression against Russia.

Even if nuclear power plants were cheaper than renewables (they’re certainly not), there is no way they could replace coal-fired stations as they come to the end of their lives. The lead time for nuclear power is just too long. As Michael West explains, there is a constellation of forces, including the Institute of Public Affairs, Putin’s mate Tucker Carlson, and the Murdoch media, pushing to keep oil and gas burning. That would have to involve new “base-load” coal-fired stations: there is no way to extend the life of our old stations for twenty or more years while nuclear power gets developed.

The other driver of the Coalition’s policy is an intention to cripple the renewable industry through creating uncertainty. That way they can confirm their claim that the government’s renewable plans are failing. It’s doubtful that any seriously cashed-up investor is convinced by the Coalition’s nuclear argument, but the belief that next year’s election could see the election of a government of Trumpian crazies is enough to make investors cautious. We are hearing accounts of local campaigns against renewable projects, based on spurious scientific and environmental claims, illustrated in a current campaign against a solar farm in Colbinabbin in central Victoria. The Investor Group on Climate Change notes that investors are getting cold feet because of the uncertainty raised by the Coalition. There is even a risk that the Greens, in their tried ways of over-wedging Labor, could be mustering people with local environmental concerns to stall clean energy projects, as the ABC’s Jacob Greber and Melissa Clarke explain. The Business Council wants the government to get on with the job of building renewable energy capacity.

Let’s not forget transport emissions

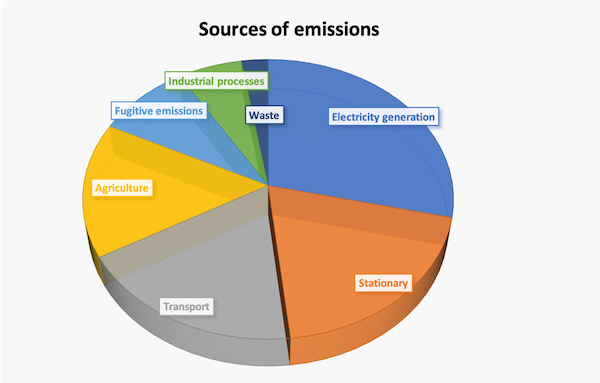

De-carbonizing our electricity network has dominated our concerns about achieving renewable energy targets, but we should note that electricity generation accounts for only about a third of our emissions, as reported by the CSIRO and shown on the pie chart below.

After electricity generation the next largest category is “stationary”, which includes manufacturing, mining, residential and commercial fuel use. This should diminish as electrification spreads – which is one reason there is such urgency in developing renewable sources for electricity, because demand is growing quickly.

Transport is the next big sector. Thanks in part to belated and modest changes in vehicle emission standards, and to vigorous competition in the global electric car sector (we benefit from other countries’ tariffs), there should be progress in reducing emissions from cars and light trucks.

But that leaves out heavy vehicles – semi-trailers, b-doubles and road trains. It will be some time before these will be driven by hydrogen fuel cells or batteries, and in any event trucks are an expensive way to move freight long distances.

Even though our settlement pattern is one of concentrated centres with large separations, which should be ideal for rail, very little of our freight is moved by rail.

Needs a little maintenance

Our rail lines are old, our rail network is fragmented, our railroads do not integrate with ports and urban roads, and around our population centres our rail lines are congested. As a result only two percent of freight between Sydney and Melbourne, our busiest route, is on rail. Even in the US, the country that pioneered the long-distance freeway network, more than a quarter of freight is carried by rail.

David Claughton of ABC Rural draws on data provided by the Australian Railway Association to demonstrate how moving freight by rail rather than road could help Australia reduce carbon emissions.

The shift to rail can be achieved. There is some progress in developing urban freight hubs and connections to ports, but the trend is still towards road transport. Proper road charging, including a carbon price on trucks, could utilize price signals to nudge a shift to rail freight.

Let’s not forget the workers in coal-fired power stations

The Coalition has an imaginative plan for coal mining workers who lose their jobs as coal-fired stations close down. Let then hang around, unemployed, for twenty or thirty years in the joyous expectation that they will eventually have jobs building and operating nuclear power stations. Attrition should cover the fact that nuclear stations are less labour-intensive than coal-fired stations.

Those concerned with practical policy issues recognize that the closure of coal-fired power stations will result in significant labour displacement, and there is rarely suitable alternative employment in the regions affected.

Adam Triggs, writing in The Conversation, describes a simulation of closure of a coal mine in the New England region, involving 766 people losing their jobs: Australian coal mine and power station workers’ prospects look bleak – unless we start offering more targeted support.

Those with skills in demand, and who are willing to relocate, would be able to find new jobs, but of those not willing to relocate, most workers (57 percent in the scenario Triggs describes), would still be unemployed after four years. And that’s without considering the multiplier effects in the local communities, as well-paid coal miners lose their jobs.

Collapsing real-estate prices has much to do with people’s unwillingness to relocate. Also, over many years, coal miners and other workers associated with power stations have gained high rates of pay, which would not be matched in other industries.

While some miners in other industries see mining as a means to accumulate personal financial wealth for a few years, riding the waves of the commodity cycle, the coal mines attached to power stations, up to now, have been considered as part of a long-lasting system. In particular fly-in-fly-out mine workers in other industries do have the pull of sunk investment in real estate or attachment to a local community.

As the title of Triggs’ article suggests, the closure of coal-fired power stations requires targeted support. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. In some but not all regions there will be jobs in renewable energy. Some other regions may be able to develop alternative industries. For others relocation assistance may be necessary. It’s not only a question of equity and social justice for people who have been serving our needs for 100 years and more; it’s also about making sure that there does not develop a hard core of people resentful at having been made to bear the cost of structural adjustment. Such resentment fuels ugly and destructive political movements.