Democracy at home and abroad

The fault lines in American democracy are following a pattern with chilling similarities to the rise of authoritarian communism and fascism in Europe last century. More worryingly, although scholars have been predicting and illustrating this development for many years, such clarification has been ineffective in arresting democratic backsliding.

The links below are to writings published before the Trump assault – an event that is more likely to stimulate the hot pens of outrage and fear, rather than careful analysis of substantial threats to democracy in America and Australia.

Australian democracy in better shape than in most countries but under threat

On Tuesday the Department of Home Affairs published a report optimistically titled Strengthening Australian democracy: a practical guide for democratic resilience.

The general tone is upbeat. It celebrates Australia’s history of “pioneering electoral inventiveness”, including the secret ballot, women’s suffrage, compulsory voting and preferential voting. Our democratic institutions are “robust” the authors claim and they note our high rankings in international indexes of democracy.

It would be surprising if our government did not take such a positive approach, but as we dig into the report we see acknowledgement of the fragility of our democracy and democracy throughout the world.

The authors draw on the findings of the Edelman Trust Barometer, which identifies four forces that have put Australia “on the path to polarisation”. These are economic pessimism, the view of government as unethical and incompetent, class division, and the battle for truth.

That is not to suggest that political harmony is an unambiguous good. The countries with least polarization on the Edelman Barometer include China, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. But the authors of the government report note that in Australia political division is becoming entrenched, and that people are becoming disengaged and cynical about democracy.

We are more satisfied with democracy that the people of the United States and UK, but our satisfaction has been falling over the last few years.

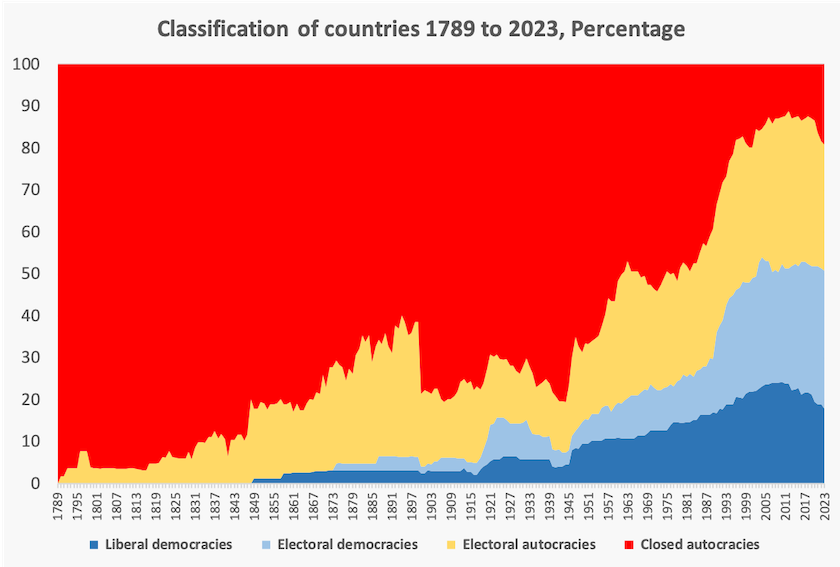

The report includes a chapter on worldwide democratic backsliding, drawing attention to long-term trends in democratization. Starting in 1945, in what historians refer to as the “postwar period” the number of “liberal democracies” (countries with voting rights as well as robust institutions defending freedoms) steadily rose from 12 to 43, but since 2008 (the year of the Global Financial Crisis), the number of “full democracies” has slipped back to 32. This is shown in the chart below, constructed from data on the Democracy website of Our World in Data. (A version of the same graph is in the government report).

Note the jump in at least partial democratization around 1990, when Eastern European communism collapsed, and reversal over the last 15 years.

Many countries have slipped from “liberal democracies” to “electoral democracies” – countries with contested elections, but without strong supporting institutions such as press freedom and independence of the judiciary.

Note that the graph relates to the number of countries. The classification “closed autocracies” includes China, and the classification “electoral autocracies” includes Russia and Iran – all large countries. In fact 70 percent of the world’s population now live under some form of autocratic rule.

Minister O’Neill covered the Australian aspects of the taskforce’s work in a speech at the Museum of Australian Democracy, at an event releasing the report. That speech covered four general threats to Australian democracy – mis- and disinformation, foreign interference, polarisation, and a weakening in public trust in democratic institutions. There is nothing new about disinformation or foreign interference, but technologies, including social media, have vastly expanded the extent and reach of these menaces.

The ABC’s Nelli Saarinen covers some of the Minister’s unscripted comments in a report on the event: Democracy is 'backsliding' and needs to adapt to modern threats, Clare O'Neil warns. She mentions the work of foreign adversaries who “sow discontent and disunity”, and the recent physical attacks on government offices: "these are the measures of autocrats, despots and tyrants. They have no place in our democracy."

Neither the report’s authors, nor the minister, call out some of the more basic drivers of discontent, particularly the “small government” dogma that has infected both Labor and Coalition governments. Because our weakened government has lost much of its capacity to provide public services, trust in government has eroded and there has been social division as the well-off separate themselves from the community in private schools, private health insurance and socially segregated suburbs. Nor do the authors mention the specific actions by federal Coalition politicians to foment discontent and distrust, or the unending barrage of misinformation and disinformation from the Murdoch media.

What Australians think of democracy

The latest Essential Report has four sets of questions relating to our views about and engagement with political institutions and practices.

The first set is about satisfaction with politics in Australia. We’re not very satisfied with democracy (37 percent), less satisfied with federal parliament (29 percent) and even less satisfied with political debate (25 percent). Younger people and Labor voters are much more satisfied than older people and Coalition voters, a finding suggesting that some people confuse the outcomes of the democratic process (delivering a government to their liking) with the institutions.

The second set is about the motivations of politicians. Three quarters of us believe that “most politicians enter into politics to serve their own interests”. Labor voters are a little more likely than other voters to believe that politicians are motivated by a chance to serve the public interest.

This shows a worrying level of disconnection. Federal politicians are well-paid, but the work is gruelling. There are a few time servers in safe seats, and some who grovel for their opportunity to enjoy the fleeting fame of a ministerial appointment, but most politicians are motivated by some vision of the public interest, even if that vision is way out of alignment with Australians’ values.

The third set is about people’s views on the best way to form government. Do we prefer majority government or a government comprising a party that has to negotiate with other parties and independents? We are evenly split on this question. But there are significant differences according to gender (men like majority government), age (the over 55s are particularly attached to majority government), and voting intention (unsurprisingly Green, minor party, and independent voters aren’t enthusiastic about majority government).

It is notable that the voting intention section of the same Essential poll shows the total Labor plus Coalition support to be only 62 percent (Labor 29 percent, Coalition 33 percent). The chance of a majority government at the next election is slim, and the chance of a party having a Senate majority is close to zero.

The fourth set of questions is about engagement with politics. In rough terms, half of us are engaged, half are disengaged. Men are more engaged than women, but otherwise there isn’t much difference according to voting intention and age, other than a finding that Green voters are a little less engaged than others.

Mapping American democracy

In a study of political beliefs and voting patterns, Dante Chinni and Ari Pinkus of Michigan State University have identified 15 groups which we might expect to have very different views on public policy.

The groups they studied are geographically-defined stereotypes, such as “Ageing farmlands” and “Evangelical hubs”(conservative stereotypes), and “Big cities” and “College towns” (liberal stereotypes).

In fact they found a great deal of agreement “on issues and policies where government has a serious role – such matters as taxes, immigration, the state of the economy and even abortion”.

One may ask, therefore, why the country is so divided. They go on to suggest a reason:

But when the topic turned to “culture war” issues (religion, gender identity, guns, family values), the differences were deep.

The results, including maps and graphs of voting patterns for each stereotype, are in a Conversationcontribution: Surprise: American voters actually largely agree on many issues, including topics like abortion, immigration and wealth inequality.

This division works strongly against a government or party trying to focus on policy, when its opponents are stirring up culture wars.

Socrates on democracy

Some political philosophy lite – a 4 minute-you tube on Why Socrates hated democracy by the School of Life.

For conservatives, it’s confirmation of the benefit of a limited franchise. For liberals it’s confirmation of the need to ensure that citizens are educated and engaged with public life.

The consequences of assassination

In his Policy Post Martyn Goddard has an article Assassination: the political strategy nobody admits to. Describing many cases, starting with the killing of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, he covers the consequences of assassination: “they are unpredictable but can linger far into the future”. And he discusses the ethics of assassination: “perhaps the most cogent argument against assassinations is that they have a very strong tendency to make everything much, much worse”.