Economics

Unemployment – still trending upwards

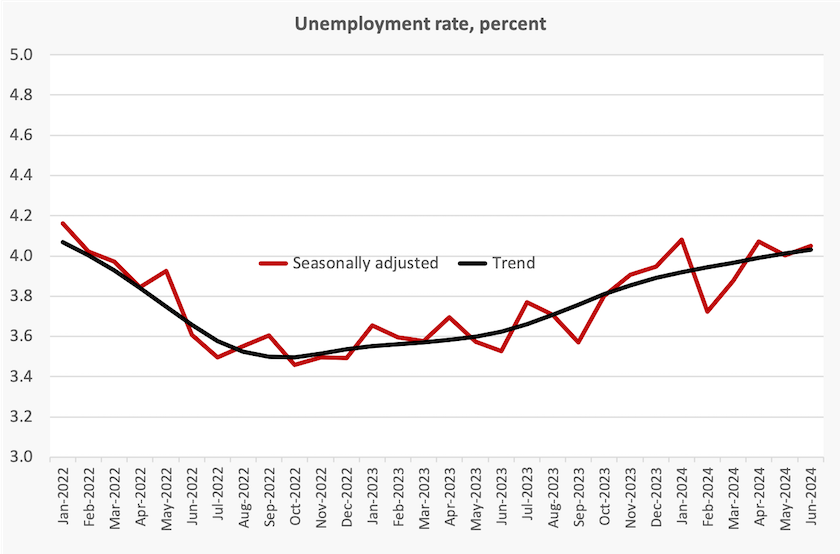

The June labour force statistics show that the labour market is little changed, but the unemployment rate is still trending upwards.

The Reserve Bank’s interpretation of this data will influence its next interest rate decision, on August 4-5. There is nothing indicating an overheated labour market that could justify a rise in interest rates,

Inflation – let’s stop chasing a single number

When the ABS releases the CPI figures at the end of this month, the eyes of the media will be on the headline change in the CPI between June 2023 and June 2024, such attention being based on the assumption that if the figure is greater than 3.0 percent, the RBA will surely lift interest rates.

But the RBA is not some automaton like the thermostat in your house or the cruise control in your car. Its task is to exercise informed judgement, and it should take many factors into consideration:

- The CPI is not a measure of inflation. Rather, it is an indicator of consumer prices in capital cities. Importantly it has an intrinsic bias to overstatement, namely the substitution effect, which is particularly strong when the prices of individual items are moving at different rates.

- The year-on-year figure is not an indicator of what inflation is now. It is based on data that is more than 12 months old. This is particularly relevant when the CPI is falling, as is the present trend.

- As the textbooks stress, the interest rate is a blunt instrument, that works primarily to suppress or to stimulate aggregate demand. It operates with a lag, which means central banks are prone to overreaction. And for many items demand is income-inelastic: most people will beg, borrow or steal to pay for basics such as health care, insurance and gasoline.

- Prices may rise because of a positive feedback cycle when “demand-pull” inflation results in “cost-push inflation”, which in turn stimulates “demand- pull” inflation, in an unstoppable and sometimes accelerating loop. This is quite different from a rise in prices resulting from price adjustments necessitated by the need for more efficient or fairer resource allocation, for example the need to bring the externalities of fossil fuel use to account, and to pay for wage rises in industries that had been taking advantage of wage theft. Monetary policy can and should deal with the former, but should be neutral with respect to the latter, even they both show up in CPI figures.

- Only some wages, the main drivers of cost-push inflation, are set in unregulated markets. In Australia many wages are set in awards and in the public sector.

Such considerations have led Alan Kohler to explain why monetary policy can be ineffective in a short video More rate rises won’t fix inflation, and here’s why. Rents, insurance and gasoline are the main elements driving CPI inflation, and raising interest rates won’t do anything to stop their prices rising.

In fact higher interest rates can stimulate rent rises in two ways. Many property owners, who have borrowed heavily to fund “investment” properties, will pass on interest-rate increases. Some others, aware of their over-borrowing, will sell their properties, possibly helping the supply situation for house buyers but tightening the market for renters and therefore stimulating price rises.

Those considerations are all within the RBA’s and the government’s objectives of keeping inflation within a two-to-three percent band. John Quiggin is one of many economists to question the desirability of targeting a specific low rate of inflation (two percent in some countries): Low inflation targeting is such a dubious idea. Why did the Reserve Bank adopt it in the first place?. Monetary policies directed at a low inflation target almost inevitability lead to the misery of austerity.

Quiggin suggests perhaps four percent may be a reasonable inflation target, which would still allow other forces to keep wages and prices under control.

Perhaps he might have advocated 4.2 percent in recognition of Douglas Adams and the fact that these targets are never fully and clearly explained to the public.

We’re doing OK on economic mobility, but there are bumps ahead

If you are poor, what are the chances you will break out of poverty? Or, at least, what are the chances your children will do better in life than you?

These are examined in the Productivity Commission’s research paper Fairly equal? Economic mobility in Australia. The Commission has looked at three interrelated dimensions of mobility:

- mobility over the course of one’s life,

- mobility from one generation to the next,

- the chances of people escaping from poverty.

In terms of intergenerational mobility we do rather well in comparison with other countries. We’re up there with the Nordic countries, Switzerland and Germany, rather than more class-bound countries such as the UK and the US.

But not all Australians are equally mobile. The Commission identifies low mobility among renters, people with low education levels, and people suffering from poor health. Many people have comparatively short spells in poverty, but the longer those spells, the fewer the opportunities to break from poverty.

It finds that wealth inequality tends to be stickier than income inequality. We have more opportunity to change our income than to change our wealth. That means there is a disproportionate level of stickiness not only at the bottom of the wealth distribution, but also at the very top. (Think private schools, the bank of mum-and-dad.) Most of the churning is in the middle classes.

While the report itself is available in the link above, Commission Chair Danielle Wood has also written about the work in The Saturday Paper: The state of Australia’s economic mobility.

The report itself is mainly about the absolute damage of poverty, and the economic opportunities lost when immobility prevents people from realizing their capabilities. Danielle Woods’ article also emphasises the importance of the fair go. “Is Australia really a nation where talent and hard work matter more than the circumstances of your birth in determining your lifetime economic outcomes” she asks.

She brings to bear some of her experience from her time as CEO of the Grattan Institute, particularly the Institute’s work on education. Our high rates of mobility are due, in large part, to our having had a strong system of school education that supported mobility, but this may not be sustained, she warns:

Data from the OECD suggests, however, that the performance of Australian school students in reading and maths is going backwards with significant declines in our levels of achievement since 2000, when the last of the Xennials [people now in their mid 40s] was finishing high school.

Disadvantaged kids particularly are being left behind. More than half of the most economically disadvantaged 15-year-old students in Australia are not proficient readers. Analysis from the Grattan Institute shows the disparity in outcomes was worse in Australia than in Canada or the UK, and on par with the less-mobile US.

Productivity – still stuck on zero productivity growth

In the March quarter there was no change in productivity. There was a 0.1 percent increase in GDP and a 0.1 percent increase in hours worked, meaning labour productivity did not change at all.

That’s the headline finding in the Productivity Commission’s Quarterly productivity bulletin, covering the March quarter 2024.

Most of the growth in employment has been in the non-market sector, particularly health care, while employment fell a little in the market sector.

This means productivity rose in the market sector while it fell in the non-market sector. But these results are partly artefacts of measurement. There was strong productivity growth in the mining sector, but this is almost certainly a reflection of strong commodity prices. There was apparent productivity growth in the finance sector, which hasn’t produced any innovation of value since the ATM.

Because of the way productivity is measured (or isn’t really measured) in the non-market sector, productivity figures as measured are close to meaningless, even though better or worse performance in health care, education, policing have more consequences in terms of human welfare than the profits and losses of mining companies and banks.

There is no quick fix to low productivity, and therefore to our stagnant real wages. It’s a result of decades of lazy public policy over the last 30 years, mainly on the Coalition’s watch, while our governments frittered away the benefits of commodity booms in tax cuts and failed to address in structural reform.

Found – 100 000 empty homes and that’s just in Melbourne

Prosper Australia, an organization seeking a shift in our tax and other economic incentives – a shift that “realigns our taxes with our values”, has produced the eleventh of its Speculative Vacancies Report on housing.

It finds that in Melbourne around 100 000 dwellings were empty or barely used in 2023. These tend to be concentrated in the inner-city regions.

The researchers base their estimates on recorded water usage. “Empty” homes are those with zero water use, while “barely-used” homes are those using less than 50 liters a day – about one five-minute shower – or a quarter of the 200 liters used in the average single-person household. The number of “empty” homes has been comparatively constant over the years, at about 30 000, while the number of “barely-used” homes has risen from about 45 000 to 70 000 over the last five years. These would include short-term rentals such as Airbnb.

Why so many? Perhaps we might consider the incentives facing a so-called “investor” (I prefer “idle speculator” so as to distinguish them from people who invest in productive assets). Tenants are such a bother, and agents take a big unearned portion of the rent. Encouraged by a permissive regime of capital-gains taxes, speculators are effectively engaged in a process equivalent to “land banking”.

This is economic waste – the waste of unused assets. As the authors say:

Vacant properties highlight inequality and how housing supply is held hostage by speculative incentives driven by tax structures that reward unproductive asset holding and penalise productive activity.

One may believe that a vacant-property tax may be the best policy solution, but the authors prefer a general land tax, arguing that it is more administratively simple, and is more likely to encourage the construction of new supply.

Land taxes are set by state governments. The Commonwealth could help by restoring the capital gains tax system that the Howard government vandalized in 1999. That previous system taxed capital gains at 100 percent, but with an allowance for inflation. The Howard government cut the rate to 50 percent, but at the same time abolished the ability to index purchase prices to inflation (reportedly because the then Treasurer found the arithmetic of indexation too difficult).

That change has given an incentive for quick turnover, comparatively disincentivising long-term patient housing investment such as build-to-rent. Many people calling for reform of capital gains tax forget about the benefit of indexation. Restoring it to 100 percent, with inflation-adjustment and without any discount, would be far less distortionary than proposals simply to reduce the discount.

Our struggling CEOs, whose pay fell by 0.2 percent in 2023, to $3.87 million

The Australian Council of Superannuation Investors has produced its report on CEO pay in ASX200 companies, revealing that the median “realised pay” (cash including bonuses plus the market value of shares) of CEOs in the top 100 companies was $3.87 million, down from $3.93 million in the previous year. The realised pay for CEOs in the companies ranked 101 to 200 also fell, to a paltry $1.95 million.

These are median figures. The average pay is much higher – $5.03 million for the top 100, $2.52 million for the next rank. The two top realised pays were for Mick Farrell of ResMed ($47.48 million) and Robert Thomson of News Ltd ($41.53 million), both foreign-domiciled companies. Greg Goodman of Goodman Group came in a distant third with $27.33 million.

ACSI points out that in the ASX100 only 2 companies did not pay a bonus. Does this mean the 98 other companies enjoyed exceptional performance, due to the ingenuity, creativity, intelligence, discipline and effort of their CEOs, or that bonuses are now simply part the culture, like tipping in US restaurants?

They also warn that CEO pay is likely to rise substantially in coming years, as revealed in some of the pay deals (recorded as “reported pay”, which includes the present value of promised future benefits).

The strong, if not explicit, message in this report is that boards could be more vigilant in attending to the interests of owners (the millions of superannuation investors), ensuring that CEOs’ and senior managers’ pay aligns with shareholders’ interests.

ACSI’s concerns with executive pay are twofold. When executive pay reaches a certain level, it starts to be at the cost of immediate return to shareholders. The other, and main, concern is with the incentives built into executives’ pay – to ensure they are aligned with shareholders’ long-term interests.

Writing in Eureka Street – The problem with CEO pay rises – Joe Zabar of Mercy Works and ANU considers the hypocrisy of business spokespeople arguing against increases in minimum pay while turning a blind eye to the seven-digit pay packets of corporate executives. He sees much of the problem in terms of corporations’ market power:

We have been failed by successive governments that have allowed the self-interest of corporate Australia to trump the common good. We have seen market power grow overtime in sectors such as energy, insurance, banking and retail to the detriment of society as a whole. Market power is a function of competition and the lack of effective market competition in many of our sectors has made the current cost of living crisis worse.

He believes, however, that the government is doing too little “to curb the insatiable appetite of corporate Australia to maximise their financial position at whatever cost to the common good”.