Australian economics

ASIC – the supine regulator

In 1947 the Chifley government legislated to nationalise the private banks, but the High Court invalidated the legislation. The recently-constituted Liberal Party opposition took the side of the banks, making Chifley’s nationalization attempt a key issue in the 1949 election.

In 2024 Australian politics seems to have gone through some ideological transformation. A senior Liberal MP in opposition, armed with evidence of malfeasance in the finance sector, is calling for tougher regulation, but the Labor government is reluctant to do anything to upset the finance sector.

That’s a short summary of the political situation around the publication of the Senate Committee on Economics report: Australian Securities and Investments Commission investigation and enforcement.

Its summary is damning of ASIC:

Evidence to this inquiry has made clear the deep flaws in ASIC’s approach to investigation and enforcement. Too often, ASIC fails to respond to early warnings of corporate misconduct and does not routinely use the full extent of its powers to achieve strong enforcement outcomes. This approach fails to deliver justice to the victims of corporate crimes, undermines economic productivity and does not deter future poor behaviour.

To save us the task of wading through the report’s 206 pages, ABC investigative journalist Adele Ferguson summarises it, and the government’s response (a defence of ASIC’s weak record) in an 8-minute session on ABC Breakfast. She also has a post on the ABC written in anticipation of the report’s findings, covering the background to the inquiry. She stresses that this is not the first such criticism of ASIC, and provides figures on the organization’s compliance activities, which have evoked the response from Committee Chair Andrew Bragg:

These figures signal that ASIC has made Australia a haven for white-collar crime. ASIC has given up on their sole obligation to enforce corporate law.

Jason Harris, of the University of Sydney, has a Conversation contribution summarising the Senate report and its major recommendations for the ASIC to be split, better resourced and subjected to a review of its governance: ASIC has comprehensively failed and its role should be split in two.

The government has been defensive, and ASIC itself has been quiet, but in a short interview with Peter Ryan on ABC AM, former ASIC Chair James Shipton agrees that ASIC is flawed and needs reform.

In a post on the ABC website Ian Verrender covers Australia’s history of misconduct in the finance sector, and ASIC’s weak responses to those findings. He suggests that if US swindler Bernie Madoff had looked around the world for a place to house his crooked business he would surely have chosen Australia. The USA, with its comparatively tough regulators, was a poor choice, landing him with a 150-year jail sentence.

Wage growth – back to low-productivity normal

“Australian real wage growth among worst in the OECD” was the headline in The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald in an article by Rachel Clun. The tone of the article is that the Albanese government has failed to fulfil its promise to get wages moving again, as if that could be achieved within two years by a government that took office at a time when inflation was peaking.

Factually the report is correct, but it’s out of context because it’s not comparing Australia with similar countries. The OECD is no longer a grouping of high-income “developed” countries. Among its 38 members are poor Central and South American countries, including Mexico, Costa Rica and Colombia, and several Eastern Europe countries still growing strongly from a low base when European communism collapsed in 1989.

The data is available on Page 31 of the OECD document Employment Outlook 2024: the net zero transition and the labour market. That shows, in general, wage growth over the last year has been low or negative in high-income OECD countries, including Australia, contrasting with reasonably strong growth in poorer countries.

In fact the report is reasonably positive about Australia, noting our comparatively low unemployment and strong growth in labour force participation and employment. The picture it paints of Australia is of a country with a well-regulated labour market, in which average wages have fallen back a little as more, and presumably less productive, workers have entered the labour force. That’s quite in line with economists’ models.

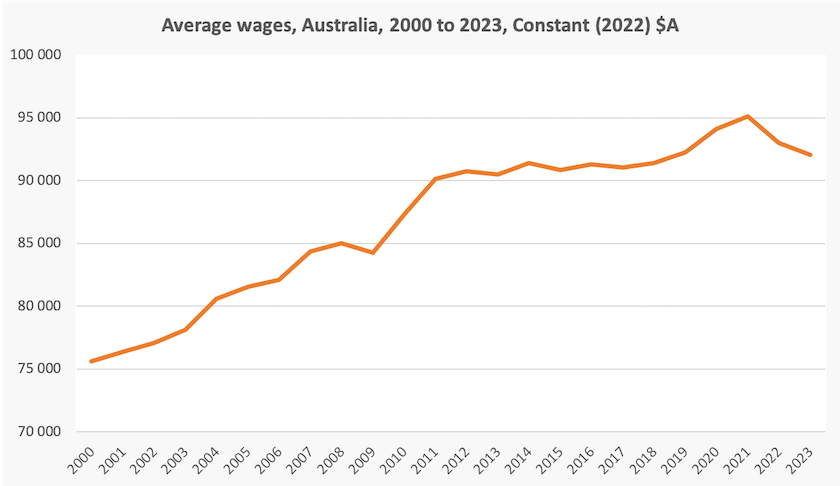

We can get a more complete picture of Australia’s wage performance from a longer time series of OECD data, from which the graph below is developed.

Wages grew rapidly up to the 2008 global financial crisis, and then grew in the post GFC recovery, before stagnating for 5 or 6 years. Low interest rates and the pandemic fiscal stimulus boosted wages for a little, but they have now fallen back to the pre-pandemic flat line.

This is consistent with the economic performance of a country that has neglected, over many years, structural changes and public investments that would have increased productivity. Recovery will be on a long, slow path.

We should expect something better from journalists than to fall back on OECD comparisons, and to make a headline out of one year’s data.

How we have fared since Covid – not too badly

We know that everyone’s doing it tough, a belief confirmed every time we go to a supermarket, hear a journalist reminding us of our “cost of living crisis”, or hear Treasurer Chalmers telling us we’re all “under the pump”.

Not so fast. ANU researchers Ben Phillips and Matthew Gray have just published in The Conversation a summary of their work on changes in living standards: Who’s better off and who’s worse off four years on from the outbreak of COVID? The financial picture might surprise you.

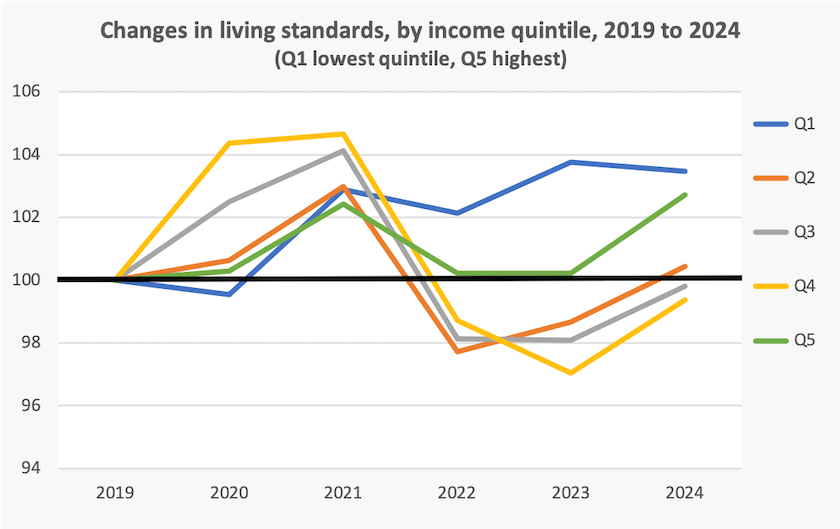

In a nutshell, for most Australians our living standards have improved since 2019, and for those whose standards are still a little below 2019 standards, they are catching up quickly. The researchers’ main graph is reproduced below, revealing that the strongest gains have been by people in the top and bottom income quintiles.

Note that for the middle 60 percent their toughest times were in 2022 and 2023, but they are now pretty well back to 2019 standards.

These are broad categories, and, as the researchers point out, there are other ways of categorizing the population, revealing that some are really having a hard time. On average those who have a mortgage have gone back by about 4 percent. Because that category includes many with low mortgages, the reversal must be far worse for those with recent mortgages. People living off investment income have done well, while the incomes of people who classify themselves as “employer” have slipped by about 10 percent. (This reflects a significant flaw in our system that taxes passive investments much more lightly than earned business income.)

Their summary:

Overall, we did not find that household living standards have dropped remarkably since the onset of COVID. But we can understand why some Australians, particularly middle-income Australians with mortgages and middle-aged Australians, feel they have.

So why are journalists, including many in the ABC, talking about a “cost of living crisis”, as if this bungling Labor government has somehow put the economy into reverse, providing an easy base for the Coalition to call the government economically incompetent? That’s misinformation with a partisan bias.

Taxes now and into the future

Two weeks into the financial year most Australians are on a wild spending splurge, having received their first pay after the tax cuts. Houses are being re-furnished, cars are being replaced, and top-end restaurants have never been so busy. Experienced economists now believe there is no option but for the Reserve Bank to hike interest rates to suppress demand.

Seriously though, consumer sentiment is low, and people are becoming more nervous about their employment security.

In the ABC program The Money three economists – Kristen Sobeck from ANU’s Tax and Policy Institute, Matthew Bowen from ING Bank – and Alex Robson from the Productivity Commission – share their insights on the way consumers are spending, or plan to spend, extra bits of disposable income: How do people plan to use extra money from Stage III tax cuts?.

The short answer is that most people intend to use any increment in income to save, through building up their own assets, or by paying down debt, such as mortgage debt or HECS.

The only people who plan to splurge are the Millennials, who have travel in mind. That suggests the tax cuts could have been fairer, but if it’s overseas travel they will be stimulating some other country’s economy, not ours.

There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that could possibly justify a rise in interest rates.

In any case if we want to stop the well-off from splurging and over-stimulating demand, why not tax them? The ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences has a website with a short message: Should we tax the rich? Research says yes. It’s pretty well basic and conventional Economics 1, acknowledging the arguments about taxes and incentives, and coming down on the side of increasing taxes.

Book now and save the date – Joseph Stiglitz is coming

Joseph Stiglitz is coming on a five-city speaking tour, starting in Sydney and moving on to Hobart, Melbourne, Canberra and Perth, with a different economic topic in each city. His first session will be a joint one with Malcolm Turnbull.

See the Australia Institute website for dates and details of each session, and an opportunity to reserve your places for a modest fee.