Europe’s elections

There is relief because the voters of France and Britain rejected the far right, but the story is much more complex and challenging.

France – age and deindustrialization sustain support for the far right

The general media interpretation of France’s second round election is that Macron’s gamble has paid off, and through a deal with parties on the left and centre he has cleverly thwarted an attempt by the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) to form a majority in the Assemblée Nationale (parliament).

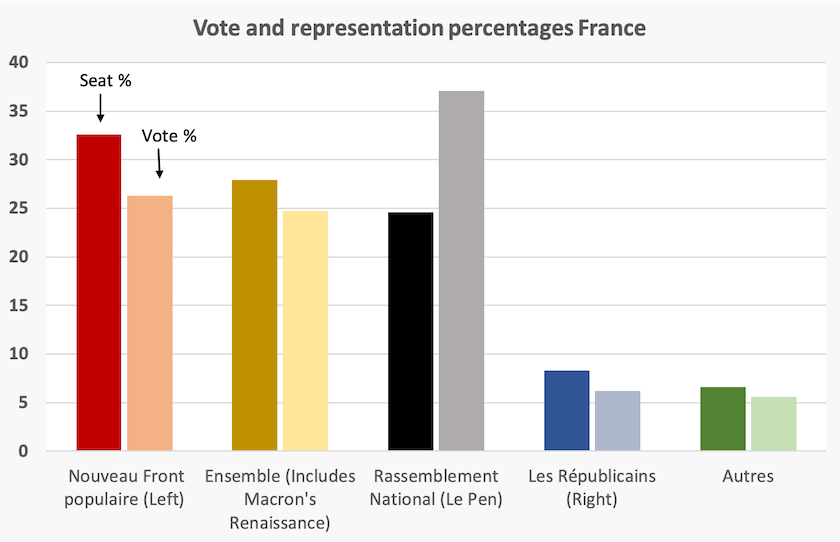

In fact RN did rather well, winning 37 percent of the vote, but because their support was regionally concentrated, they won only 25 percent of seats.

Most media emphasize the outcome of elections in terms of seats won, but to understand the mood of the people it’s more informative to focus on the way people vote. The graph below shows both – the distribution of seats won (saturated colours) and votes (faded colours). The far-right RN had strong voter support, while the left Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP) and Macron’s Ensemble did better in terms of representation than they did in voter support.

It could have been worse, but for the deal negotiated between the left NFP and Macron’s Ensemble to engage in strategic voting in the second round. That strategy involved candidates from parties with low chances of winning deliberately failing to nominate, thereby rendering the contest for the most part as binary “RN” vs “Not RN”.

This strategy was necessitated by a peculiarity in France’s two-round system. In most countries with two rounds of voting the second round is restricted to the two leading candidates in the first round, but in France only the very weakest candidates are eliminated, meaning there are often three or more candidates in the second round.

Only the French could develop a process that has the inconvenience of two-round voting, while preserving the distortions of first-past-the-post voting. Even Iran has a more rational system.

From here it’s becoming messy, explains Romain Fathi of the ANU writing in The Conversation: French say “non” to Le Pen’s National Rally – but a messy coalition government looks likely.

It’s particularly messy because those bars in the chart above aren’t political parties. Rather, they’re loose gatherings of parties that came together to defeat RN. As the ABC’s Europe correspondents Kathryn Diss and Riley Stuart explain, the NFP includes everything from communists through to economically conservative social democrats. Emmanuel Macron's election gamble foiled the far right, but threw France into political chaos.

Possible outcomes are covered in an 8-minute conversation on the ABC’s Breakfast program between presenter Steve Cannane and Rick Noack of The Washington Post: Second round of French elections leaves no clear frontrunner. It is up to President Macron to appoint a prime minister, and so far he has re-appointed Gabriel Attal, a member of his own Renaissance Party. The problem Macron faces is that while his own party’s platform is fairly market-oriented, potential colleagues on both his left and right are more in favour of increased public spending. (Perhaps Macron regrets that in 1793 France closed off the option of handing the task of deciding who should form government to a king.)

The geographic pattern of French voting is revealed in two informative maps, one for each round of voting, presented by the ABC: French politicians surprised by swing to the left as parliamentary polls close — as it happened. (In case that website is taken down, there are similar maps, using a different colour scheme , on Politico: How France voted: Charts and maps).

In the first round there was strong support for RN in almost all non-metropolitan regions. In the second round, however, much of that vote came back to Macron’s Ensemble and the NFP on the left. The RN vote held up only in two distinct bands – one in the northeast, and the other in the south along the Mediterranean coast. The northern band, along the Belgium-Germany border, is a once-industrialized region, where many jobs have been lost over the last 50 years. The southern band is where many people retire, described by The Economistas having politics that are more like Florida’s than California’s.

Notably in both rounds there was strong turnout – above 60 percent which is high for France – breaking from a trend that had seen turnout slowly falling over many years.

This voting pattern is consistent with the possibility that many people lodged a protest vote in the first round, while their second-round vote was more considered. The concentration of the RN vote in regions with older populations suggests that in coming years demographics may work against France’s hard right.

United Kingdom – the distortions of the “Westminster” system and first-past-the-post voting

In 2011 the Liberal Democrats, the junior partner in a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, suggested that the country’s elections should use what the British call an “Alternative Vote” (AV) system. That is what we call “preferential voting” and what most of the world calls “ranked-choice voting”. The Liberal Democrats’ platform is actually for proportional representation: their AV offer was a compromise.

Adam Webster of Oxford University, writing in The Conversation, explains that the Conservatives rejected the idea: The Conservatives may regret campaigning to keep first past the post in 2011.

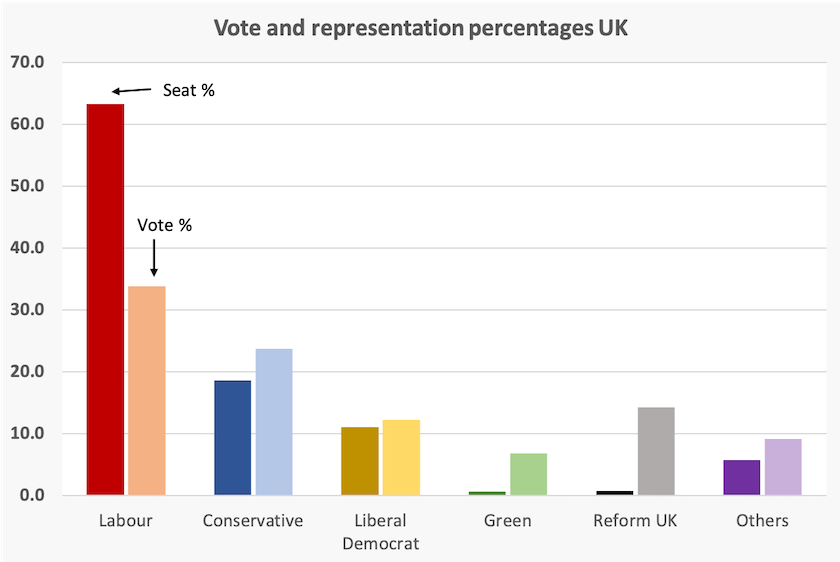

That adherence to first-past-the-post voting system helps explain why, with 34 percent of the vote, Labour won 63 percent of the seats in that country’s “House of Commons” – what is known as the House of Representatives in Australian and the US. By comparison in our election in 2022, with 33 percent of the vote our Labor Party was only just able to scrape together majority government, illustrating the different outcomes delivered by first-past-the-post voting and ranked-choice voting.

The outcome of the UK election, comparing votes won and representation, is shown in the graph below. Every party other than Labour has less representation than their share of the vote would indicate – particularly the far-right Reform UK and the Greens.

We don’t know what the outcome would have been under an AV system, but we do know what it would have been under proportional representation – see the pale bars in the graph. Labour would be now trying to cobble together a Labour-Liberal Democrat-Green coalition, similar to Germany’s Straßenampel coalition, or, less likely, a Labour-Conservative coalition, similar to what Macron stitched together to fend off the far right in France. To see what the UK House of Commons would look like with proportional representation the Electoral Reform Society has prepared some rather neat graphics.

Of course such alternative outcomes are hypothetical, because different voting systems elicit different strategies by parties and different behaviours by voters. When there is first-past-the-post voting, and polls are predicting a big win for a party, voters make the rational decision that there’s not much point in casting a ballot. UK voting turnout has been on a long-term slide, from about 80 percent in 1950 to about 50 percent now. That means the support of about 20 percent of eligible voters (0.6 X 0.34) delivered Labour a landslide majority. We can imagine scenarios where such arithmetic helps sustain authoritarian anti-democratic governments.

That isn’t to suggest that Labour would not have won under alternative voting systems, but it does point out some of the consequences of first-past-the-post voting. There aren’t many people left in their parliament who can pull together to hold Labour to account, and those Conservatives who remain are likely to be representing the least progressive constituencies. By convention the Conservatives will probably be designated as the “opposition”, but that would mean the 43 percent of people who voted other than Labour or Conservative are left out of the Westminster two-party system – a system now well past its use-by date.

Recognising their weakness, the Conservatives may try to get together with Farage’s Reform Party, and form a right-wing opposition. In its insightful and concise article How shallow was Labour’s victory in the British election? (paywalled but with some concessions) The Economist notes that “the Conservatives will face the temptation to try and colonise the Reform UK vote rather than the harder task of converting Labour voters over to their corner”. Comparisons with our Liberal Party and the National Party, and their dalliances with One Nation, come to mind.

There are informative maps of voting outcomes in The Guardian and in the House of Commons Library website. Some commentators have noted that the electorates that turned most solidly against the Conservatives are the same electorates that voted strongly for Brexit in 2016. It’s as if the UK, like Poland, has had a dose of populism, and now understands where it takes a country.

Many media refer to a swing to the “left”, but in fact Labour’s vote was only a little up on the previous election. In fact it was a catastrophic collapse in Conservative support, confirming the aphorism “Oppositions don’t win elections, governments lose them”.

There are reasons other than the Brexit disaster explaining the collapse of the Conservative Party. Its successive leaders bear more resemblance to the cast of a Monty Python comedy than to a parade of serious people concerned with the public purpose, and people have certainly turned off their austerity policies. Stephen Coleman of Leeds University writes in The Conversation Grieving and unheard, the British public has voted for change – in weariness more than in hope:

From the loss of access to GPs and dentists to the absence of textbooks in their children’s schools, to the reliance of working families on food banks to feed their kids, this was the first electorate in generations to be voting with an expectation that their lives would be materially worse than their parents’.

As they pleaded for people’s votes, politicians seemed unable to fully grasp the psychic consequences of this loss. In the case of the Tories, this was because they were widely regarded as being responsible for presiding with moral indifference over the wreckage of the UK’s social infrastructure. Labour politicians, meanwhile, bound by a self-imposed fiscal dogma, resisted any demand for radical regeneration as if it were an act of economic heresy.

To put it in Australian terms, the outcome is not a 1972-style “It’s time” moment, or even the visionary change of economic direction promised by the election of the Hawke government in 1983. It’s just more of the same austerity, to be delivered by a more competent and less corrupt government, but lacking the courage to implement a full social-democratic platform. Familiar to Australians?

That theme is taken up in a longer article by Fintan O’Toole writing in Foreign Affairs: Can Starmer Save Britain? Why Labour’s sweeping victory may not reverse the country’s decline. He writes:

Labour has accepted the very fiscal constraints laid down by the Conservatives while largely eschewing tax increases to raise the revenue it needs if it is to shore up public services and begin to make up the deficit in investment. Given the multiplying social and economic stresses facing the country, the new leadership will be tempted to avoid bolder reforms in favor of mere crisis management.

It's a different country, with a different culture, suffering an economic decline far worse than anything we could imagine. But in O’Toole’s message there is a warning for the UK government and for our government to get on with the task of governing as a social-democratic government.

Iran – an incremental shift to the left

Bearded old men were ruling Iran 2500 years ago (Persepolis)

OK – Iran isn’t in Europe, and it ranks at #153 out of 167 countries on the EIU Democracy Index. But it’s a big country, culturally very different from other countries in the Middle East, and it has had a runoff election offering choice. The first-round election was anything but fair, the hard-line Guardian Council having vetted candidates before they were allowed to stand, but because one candidate kept his ideas quiet, and because the guardians hadn’t quite done their due diligence, a reformist made it into the runoff.

That runoff was a contest between hardliner Saeed Jalili (whose politics lie in some combination of those in North Korea and Afghanistan) and Masoud Pezeshkian, described as a moderate reformer.

Pezeshkian won the runoff with 53.7 percent of the vote.

Political power still resides with Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (who at 85 is considered old even by American standards) and with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

The ABC’s Nassim Khadem believes little will change as a result of this election: Iran's new president Masoud Pezeshkian has promised reform, but can the regime change?

Writing in The Conversation Arsin Adib-Moghaddam believes that Pezeshkian’s victory won’t lead to domestic reform, even though Iranians are desperate for change, but it could see a softening in relationships with the west: Iran’s new reformist president offers hope to the west and cover for the conservative establishment.

Writing in Prospect Arash Azizi is more optimistic, noting that “Iran has a way of surprising you”. He sees the possibility of long-term reform, because it’s becoming increasingly hard for the Ayatollah and his circle of guardians to suppress the increasingly restive population. They may be coming around to understanding that “revolutionary slogans can’t run a country of 85m people”: The future of power in Iran.

Azizi is author of What Iranians want: women, life, freedom.

Pope Francis on democracy: it is not in good health

At a gathering of Italian Catholics in Trieste Pope, Francis has warned that democracy is not in good health.

There is no English-language transcript of his speech, but writing in Crux, a magazine covering Vatican affairs, Elise Ann Allen reports on its highlights : Amid spate of elections, Pope says democracy not in “good health”Pope Francis emphasizes the obligation on people of goodwill to become involved in public life. Pope Francis is concerned at the low turnout in European democracies, and at the seductive allure of populism. To quote from Allen’s account:

Pope Francis insisted that conditions must be created in which everyone can participate, saying this participation must be facilitated in young people, “also in the critical sense in regards to ideological and populistic temptations.”

He touted the role that Christians can play in promoting European cultural and social development through dialogue with civil and political institutions, but cautioned against falling into various forms of ideology.

“Enlightening each other and freeing ourselves from the dross of ideology, we can start a common reflection especially on issues related to human life and the dignity of the person,” he said, saying, “Ideologies are seductive…they seduce, but they lead you to deny yourself.”

Deutsche Welle reports on the speech, in which Pope Francis refers to the German children’s legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin: Pope Francis warns of 'populists' and ailing democracy.

His speech has two messages – one for citizens to become politically involved and not to retreat into a “private faith”, and the other for political movements to direct their attention to the marginalized, to those left behind.