Other economics

Barely living on income support

Anglicare, in its Cost of living index report, puts the case for a lift in income support for the unemployed up to the Henderson Poverty Line, government policies that would see rent increases limited, and the construction of 25 000 social and affordable houses a year.

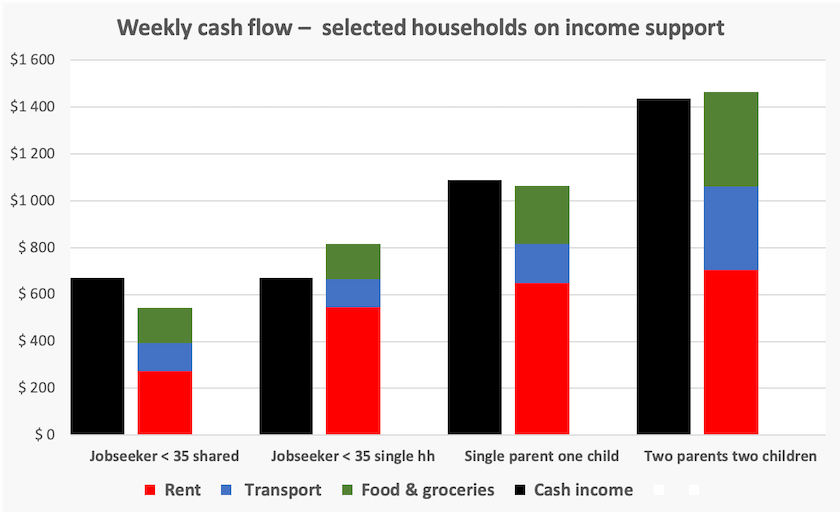

To illustrate their case, they compare the level of “JobSeeker” or Parenting Payments, supplemented with rent assistance, with the basic needs of four household types – a single JobSeeker recipient under 35 in a shared house, a single JobSeeker recipient under 35 in a one-person household, a single-parent household, and a two parent-two children household. The results are shown graphically below.

Note the significant gaps for single JobSeeker recipients in their own (probably rented) housing. Note too that for the parent households benefits just match outlays. This does not mean these payments are adequate: the Anglicare estimates do not consider clothing, utilities, telecommunications, medications and replacement of appliances for example. The implied adequacy is most accurately seen as short-term assistance to keep a household together, or even as an emergency payment.

The burden of rent payments is clear from this graph. Transport costs, too, are high – between $6 000 and $18 000 a year. No doubt this reflects the reality that for those whose employment situation is precarious the only affordable rental accommodation is in urban regions where there is no transport option other than owning a car, and where long distances have to be covered. It’s a long time since our urban geography had workers’ suburbs around places of manufacturing employment.

Is retail pharmacy about to face an “Uber moment”?

Pharmacy Guild House, Barton

If you want to learn who have been Australia’s most successful rent-seekers, benefitting from government largesse, take a drive around the Canberra streets surrounding Parliament House. On Brisbane Avenue, just 400 meters from Parliament House (the same distance as PwC Consultants) lies Pharmacy Guild House, the lavish headquarters for the retail pharmacy lobby.

Retail pharmacy escaped the Hawke-Keating reforms of the 1980s – reforms that saw the withdrawal of tariff protection and many forms of domestic restrictions of competition. It wasn’t hard for the government to take on the car industry or the airlines, but retail pharmacy belonged to the sacred category of “small business”. Pharmacies were distributed in every electorate, and pharmacists were trusted in ways that supermarkets and grog shops are not.

Hence they were able to survive as maybe Australia’s most coddled industry. A set of elaborate regulations, shaped and modified by Coalition and Labor state and federal governments, was fashioned to protect the small-volume pharmacy, owned and operated by individual pharmacists, from the horrors of the competitive market and from the emergence of US-style drugstores and pharmacy sections in supermarkets.

Even so, businesses have found their ways around these restrictions, and there is presently before the ACCC a merger proposal between two pharmacy chains, Chemist Warehouse and Sigma Healthcare.

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, describes the restrictions, the ways these businesses have worked around them, and more basic problems faced by the industry: The Chemist Warehouse deal is a sideshow: pharmacies are ripe for bigger disruption.

One aspect of this coddling has been a prohibition on price discounting. (Is the government really serious about the cost of living?) Martin writes that “the peculiar rules governing pharmacies ought to make them particularly profitable, except that they don’t, because pharmacies cost so much to buy. The benefit is baked into the price”. He draws an analogy with taxis, which were once a very protected industry. Because state governments set limits on the number of taxi licences, similar to the restrictions on pharmacy ownership, taxi licenses became more and more expensive, and the beneficiaries became the retiring owners of the licenses. As Martin says of pharmacies “The owners who sell get rich as a result of the rules, not the owners who buy”. (In the case of pharmacies another group of beneficiaries are the owners of suburban shopping centres, who see a pharmacy as a lucrative cash cow.)

Martin is optimistic about reform, believing that an “Uber moment” may have arrived for retail pharmacy.

Dampening inflation – let’s try a stabilizing index

At its meeting on Tuesday the Reserve Bank Board decided to keep its cash rate on hold. Its statement is written in an “on the one hand, on the other hand” style: maybe it is a generic statement punched out by ChatGPT. But surely AI wouldn’t have generated the curiously-worded sentence: “Conditions in the labour market eased further over the past month but remain tighter than is consistent with sustained full employment and inflation at target”. What part of “full employment” does the RBA not understand?

The next piece of data on inflation, the Monthly Consumer Price Index, will be released on Wednesday 26 June. Expect a flurry of speculation.

As has often been stressed in these roundups, the Consumer Price Index is but one lagging indicator of inflation. As the ABC’s Gareth Hutchens points out in a post There are different ways to dampen inflation. But is anyone listening?. He acknowledges that the CPI is an important indicator because many prices and contracts are linked to the CPI. He writes about how exogenous price shocks, which may have nothing to do with excess demand, ripple through markets, and result in moving the CPI. One way to dampen such feedback, he suggests, is to change the way we apply indexation to wages and contracts. Instead of using the CPI, which is self-referential, perhaps we could have a standard indexation, say at 2.5 percent, the centre of the RBA’s comfort band.

Not that it’s a current problem, but it would also have a stabilizing effect in a deflationary situation.

Is there really a cost of living crisis? Let’s see what tax stats tell us

On Monday the ATO put its 2021-22 Taxation Statistics on the web. That means it refers to income data that’s two years old, and of course we never had a “cost of living crisis” while we had a Coalition government. But it does provide the first snapshot of income distribution in post-pandemic Australia.

Many media have used the ATO’s summary data to run stories, but there is a great deal of information which researchers will wring out of the ATO’s tables in the coming months.

There are a few bits of information in this summary data that should prompt researchers to have a closer look at possible public policy issues. To note some:

Five of the ten most highly paid occupations were health professionals. Top of the list were surgeons, with an average taxable income of $460 000. The other four in the top ten were anaesthetists, internal medicine specialists, psychiatrists and “other medical practitioners”.

There were 6.7 million Australians under 65 who held private health insurance, 3.8 million of whom have individual incomes of $90 000 or less, or couple incomes of $180 000 or less. It seems that many who claim to be having a tough time financially are still wasting their money on private insurance.

The average gross salary or wage (11.9 million taxpayers) was $70 000, but the median was $58 000.

There were 2.3 million people with income from rental properties, 1.7million of whom had two or more properties. Of these 42 percent reported making a loss, presumably because of interest deductions, even though interest rates were very low over 2021-22. Many landlords must be heavily geared.

The Australia Institute has dug a little further into the data and finds there is a significant gender pay gap across almost all occupations. The higher the base occupational pay, the higher is the gender pay gap.

The ABC’s Clint Jasper has dug up some data from the Governance Institute of Australia indicating that CEO pay has grown by more than ten percent in the last twelve months. He provides no link to the data, and it isn’t on the Institute’s website, but it does align with media reports of the remuneration of executives whose pay is partially linked to share prices in a booming stock market.

In themselves these scraps tell us little, but the ATO has provided us with a rich database of the distribution of Australians’ incomes. This should allow researchers to question the common story that we’re experiencing a “cost of living crisis”. That’s a convenient catchphrase, particularly for right-wing media, for it implies that we’ve fallen on hard times since Labor came to office, exploiting the common post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacious way of thinking. That is, it’s all Labor’s fault.

More probably the reality is that many people, particularly those who have no mortgages or old mortgages with small balances, are doing rather well. Some others, maybe, have had to tighten their belts a little: the extraordinary income growth of the years leading up to 2018 was not going to last forever. And there are indeed others, including renters and those who borrowed heavily during the period of low rates who are doing it tough.

We have a problem, a bad problem, in the distribution of income and wealth. It relates to long-term structural weaknesses in our economy that have gone unaddressed for most of the years since our last bout of structural reform in the 1980s and early 1990s.

It's unfortunate that ABC journalists, who should avoid conveying an impression of partisan favouritism, so easily slip into referring to a “cost of living crisis”.

The dark forces resisting a cashless economy

Independent MPs Bob Katter and Andrew Gee have introduced into Parliament a Keeping cash transactions bill. The drafters assert that “widespread refusal by businesses to transact in cash would have significant impacts on many people in our communities, including seniors, who rely on cash to make payments”. The bill proposes fines up to $25 000 for businesses that refuse to accept cash.

Their interest is understandable. Katter’s electorate, Kennedy, in northern Queensland and Gee’s electorate, Calare, in central western New South Wales, include large areas with weak or non-existent internet services, and many of their constituents, including older and indigenous Australians, rely on cash.

They should be aware, however, that there are many on the dark side who have a strong interest in keeping the cash economy alive. Money launderers and drug dealers thrive in a cash economy. Businesses evading GST or income tax benefit from the lack of a recorded trail of transactions. The claim by Katter and Gee that “the bill will have no financial impact” does not stand up to scrutiny.

Writing in Yahoo Finance about the dark reality of the cashless fight, Stewart Perrie describes the burden imposed on business that find they have to accommodate cash transactions. Every day every cash register has to be reconciled, cash has to be held on the premises overnight, and cash surpluses have to be taken to a bank – all involving costs and vulnerabilities, including the physical safety of staff.

We would surely all be safer in a cashless society, where there is no cash to be found in shops, houses, purses and wallets. There will be exceptions: Katter and Gee rightly point to the needs of sparsely populated areas. But no business should be burdened with legislation requiring it to keep cash.

Many businesses impose surcharges for cashless transactions, claiming that they have to pay high fees to banks for that convenience. There is some truth in that claim. The incidence of such fees is the substance of a recent speech by the Reserve Bank’s Head of Payments Policy, who notes, for example, that fees fall disproportionately on small businesses. But in the same speech he notes that businesses have ways in which they can get a fairer deal, and that blanket surcharges fail to differentiate between the low fees on debit cards and the comparatively high fees on credit cards.

The same speech also covers the fees of “buy now pay later transactions”. The fees associated with BNPL are about eight times higher than those charged on debit card transactions. That means, when you see a website offering the same price of an item in four transactions, you are probably subsidising those fees when you pay in one hit. It’s better to find another site offering a lower price without a BNPL option.

In general consumers would do themselves and the public a service by avoiding businesses that impose a surcharge for cashless transactions. They may be so badly managed that they have never worked out the cost of handling cash and have no regard for the safety of their staff, or, more likely, are engaged in tax evasion.