Other economics

Dutton, always on the lookout for a way to divide the nation, re-starts the climate war

The Coalition is right: Australia is not on track to meet its 2030 target to reduce GHG emissions by 43 percent. That’s confirmed by projections published by the Department of Climate Change, Energy and Water, showing we will reach 42 percent based on present progress. The electricity sector, the sector that has to do the heavy lifting, is projected to fall short of its goals. Emissions from the agriculture sector will remain flat, and emissions from transport will actually increase.

In fact we should be sceptical of reports on Australia’s progress. In the most recent Quarterly Essay, Highway to Hell: climate change and Australia’s future, Joëlle Gergis suggests that some of that progress towards a 43 percent reduction is to be achieved through greenwashing, particularly in relation to carbon offsets, and through unproven carbon capture and storage measures.

But unlike Dutton she does not see it as inevitable that we should fall short: she outlines policies that rely on market mechanisms and re-shaped taxes, that would easily get us to our 2030 and later targets.

The Coalition’s response however is that we should stop pushing renewables, rely on gas, and some time, many years from now, we will be back to the happy days of 24/7 base load energy because we will have a network of nuclear power stations. That seems to be their policy as the ABC’s Tom Lowrey described it last week: Coalition to dump Australia's 2030 climate target, arguing 43 per cent emissions reduction is unachievable.

It’s hard to make much sense of the Coalition’s policy, particularly when, as Agriculture Minister Murray Watts pointed out on the 730 Report, in one day the opposition leader and two other senior members of the opposition made three contradictory statements about targets and their commitment to the Paris Agreement. But at 1236, on Wednesday 12 June, it seems that they have a policy of not announcing a 2030 target before the next election.

Its broad policy is most easily explained by analogy. Imagine that you have set yourself a target to lose 5 kg weight within six months. After a couple of months you realize you will lose only 4 kg, unless you do more exercise and take more care with your diet. But you abandon that goal, and decide to engage in a lazy and indulgent lifestyle, and go for bariatric surgery when your obesity becomes unbearable. Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation similarly explains the Coalition’s decision in terms of our human tendency to put off making hard decisions.

The Coalition’s policy makes no economic sense, but there seems to be a political explanation that lies in an absolute hatred of renewable energy among some influential members of the Coalition, particularly in the National Party. As Gergis says in her essay “the Coalition’s attempt to resurrect the nuclear power debate in Australia is simply a red herring intended to delay the inevitable transition to renewable energy”. She goes on to write “the Coalition’s diversion into a debate about nuclear power, like its promotion of carbon capture and storage, is a cynical effort to undermine the support of renewable energy and extend our reliance on fossil fuels for as long as possible”.

It seems to have drawn some political justification for its policy from a recent Lowy Institute poll, which found Australians have shifted their energy priorities from reducing carbon emissions to reducing household energy bills, and finds there is 61 percent support for “Australia using nuclear energy, alongside other sources of energy”.

The poll is worth a close read however. Although support for renewable energy is lower than it was three years ago, it’s still strong, and, importantly, the questions on nuclear energy do not have any information on cost or time to deliver.

The CSIRO’s GenCost report confirms that nuclear power is much more expensive than renewables, and would take at least 15 years to develop. Its analysis includes the costs of firming – which would involve the use of some gas but only as a filler, not as a base load as would be the case in the Coalition’s plan. More concise is an infographic, prepared by the ABC Digital Story Lab, with input from Alan Finkel and John Quiggin, of the numbers around nuclear energy to generate electricity. The cost would be staggering.

It makes sense for countries that already have nuclear-powered generators to go on using them, because their marginal cost of producing electricity is close to zero, and the investment is a sunk cost. But it makes no sense for a country in a latitude with huge renewable resources to build them, because renewables also have the same near-zero marginal cost but with a very much lower capital cost. The view that Australia does not need nuclear power is confirmed by Fatih Biron, executive director of the International Energy Agency.

There are calls for the Coalition to release costings and physical plans for its nuclear network, but it probably hasn’t thought these matters through. It’s confused about its commitment or otherwise to the Paris Agreement. In relation to nuclear plants there are questions of scale and connectivity – is it thinking of a few large generators, with risks of system vulnerability and the need for redundant transmission investment, or several smaller generators, which would be more expensive to achieve the same output? If, as would be inevitable, investments in renewables would dry up, would it have to resurrect old coal-fired stations or build new ones, or would it have to put construction of new gas-fired stations on a fast track? In what way could the Coalition’s plan reduce electricity prices? And the Coalition seems to be locked into a way of thinking that’s well past its use-by date, the idea of 24/7 base load power. The industry is past that, explains Giles Parkinson of Renew Economy, in an article about the two-year reprieve given to Eraring power station.

In a Conversation contribution – Peter Dutton’s latest salvo on Australia’s emissions suggests our climate wars are far from over – Matt McDonald of the University of Queensland explains the economic and foreign relations consequences that would result from the Coalition’s policies. They would do great damage on many fronts.

The politics of the Coalition’s idea are discussed on last Sunday’s Insiders. It’s a high-risk strategy, even within the Coalition. Bridget Archer has criticized the policy publicly, and journalists report that other Coalition MPs are unhappy.

Maybe it’s nothing more than an attempt to draw attention to the government’s possible failure to meet the 2030 target. Maybe it’s a sign that Dutton, taking a lead from Trump’s Republicans, has abandoned hope of winning back what were once heartland urban seats, and is putting his faith in winning outer-suburban seats. Maybe it’s a sign that the Coalition is entirely captured by the fossil fuel industry: Gergis writes in her essay “the Coalition’s diversion into a debate about nuclear power, like its promotion of carbon capture and storage, is a cynical effort to undermine the support of renewable energy and extend our reliance on fossil fuels for as long as possible”.

Or, at an even more cynical extreme, it may be a calculated attempt to sow confusion among investors, in order to thwart Australia’s energy transition. That should not be ruled out: the federal Coalition in opposition has a record of sabotaging the national interest in order to discredit Labor governments.

Inequality – boosted by the pandemic and superannuation tax breaks

The shock of a pandemic

The Productivity Commission has published a research paper A snapshot of inequality in Australia. It is actually an analysis of changes in income distribution immediately before, during, and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

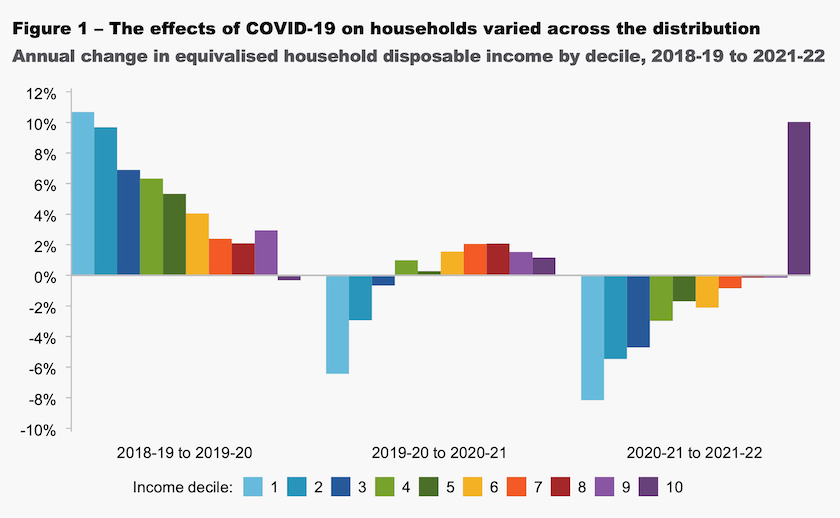

The researchers’ main finding is captured in a chart, copied below, which suggests strongly that in the year before the pandemic income inequality was falling, at the peak of the pandemic the poorest households were hardest hit while most other households maintained their income, and coming out of the pandemic inequality rose sharply. That confirms the impression that coming out of the pandemic most Australians, apart from the very well-off, have felt their economic conditions to be deteriorating. Note that this research goes up only to financial year 2021-22. By June 2022 the new government had barely found the directions to the parliamentary bars and there had been only two interest rate rises.

The report is less conclusive on wealth inequality, but it suggests that it reduced during the pandemic:

The income received over the period meant that households with lower wealth were able to increase their savings and reduce their debts, contributing to a reduction in wealth inequality. House price changes during the pandemic further reduced wealth inequality, as price growth was relatively higher in areas with lower prices, such as smaller capital cities and regional areas.

We know that subsequently there has been a collapse in saving, and it seems that house prices are now rising fastest at the top end of the market.

The report also confirms, unsurprisingly, that wealth inequality is particularly strong among older people.

Superannuation inequality

Superannuation enjoys concessional tax treatment on contributions, and once superannuants are in the pension stage earnings from the first $3 million in members’ accounts are tax free.

Minh Ngoc Le of the Australia Institute has analysed the cost of these concessions and their distributional consequences in a discussion paper Who benefits? The high cost of super tax concessions. These concessions cost the budget $55 billion in 2022-23, and their cost is growing strongly. More than half of these concessions are enjoyed by the top 20 percent of income earners.

She suggests that removing the tax concession for both contributions and earnings from the top ten percent of earners would save the budget more than $12 billion a year. This is not a specific recommendation, but it does illustrate the potential for future savings and a path to greater equity: specific policy recommendations would have to consider matters such as lifetime earning patterns, and lump-sum inheritances (which are not “earnings”).

Women retire with a superannuation savings gap of nearly 25 percent compared with their male counterparts. (This gap may close somewhat in time, because women now retiring are in a cohort that had low workforce participation. But in general women who take a break from the workforce around the birth of their children will still lose out, because contributions at an early age enjoy the benefit of a long period of compound growth.)

Some will be surprised by the finding that, in comparison with other OECD countries, Australia has a high rate of poverty among people aged 66 and over.

These findings need to be considered carefully. The paper refers to all 37 OECD countries, which includes poor countries such as Turkey, Mexico, and Costa Rica, where the definition of “poverty” may be at a much lower threshold than it is in Australia. The Australia Institute would be better-advised to use only the smaller set of high-income OECD countries for its international comparisons.

Traffic jams on Tullamarine Freeway – a legacy of Howard’s cronyism

When Melbourne’s Tullamarine Airport was opened in 1970, there was a promise to connect it to the city with a rail link.

We are still waiting, 54 years later – while Melbourne’s population has doubled and has become Australia’s largest city. Sydney, Brisbane and Perth all have rail stations at their airports.

The ABC has a post about the present situation, including a 7-minute videoclip covering the current conflicts between the airport owners and the state government.

It’s an informative explanation of the situation, and it includes the assertion that the airport’s private owners are deliberately thwarting the project, because it would rob the airport of the $150 million a year it collects in parking fees.

The explanation would have been more complete if it had included reference to the Howard government’s 1994 decision to privatize Australia’s capital city airports – a decision based either on economic incompetence or worse, on Putin-style cronyism of distributing public assets to mates.

The Tullamarine train is delayed

In Australia our capital city airports are natural monopolies that should never have been privatized. We don’t have high-speed rail capital city connections which would keep airport owners honest, and we don’t even have a fully-developed road network between all our capital cities.

In the US, a country hardly renowned for public ownership of enterprises, airports in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, and many other cities, are owned by those cities. This ownership structure not only protects against the imposition of monopoly profits, but it also allows for an alignment of incentives: the airports’ business objectives are to serve the cities.

Because Melbourne is the dominant city in Victoria, it would make sense for the Victorian government to re-nationalize Tullamarine Airport. The transaction would be neutral on the state government’s balance sheet. There would be a liability on one side, offset by an income-earning asset on the other side, which would cover the interest on the debt. In itself it would make no call on resources. That’s basic accounting.

Of course there would be a huge fuss around such a move, legal challenges about valuation, and claims that Australia is no longer a safe place to do business. But it would be no different from trust busting or removing tariff protection – cancelling an economic privilege that should never been granted in the first place. There is no economic or moral reason why we should have to go on paying for the Howard government’s economic mismanagement.