Public ideas

Mariana Mazzucato on re-thinking the economy

Mariana Mazzucato has recently paid another visit to Australia, this time capturing the attention of Treasurer Jim Chalmers.

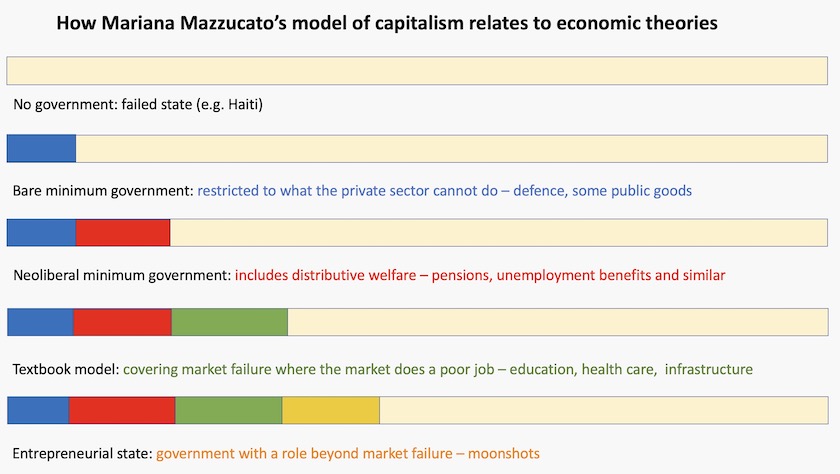

Her idea of a moonshot guide to changing capitalism is on an ABC Big Ideas program. Because she presupposes that her audience is familiar with economists’ ideas on the role of government, readers and listeners may be helped by a (simplified) explanation of where government fits into various theories, illustrated in the diagram below.

A starting point is to imagine a state with no government. There aren’t too many examples – Haiti probably comes close to such a model.

Even the most hardened conservatives believe that government must have some role in doing stuff that the market cannot do, such as providing an army and a police force, maybe the occasional street light, and perhaps some local roads that cannot justify tolling. That’s a bare minimum model. The private sector can be left to provide health care, education and so on.

But even neoliberals have some compassion, or at least are forced into compassion by political pressure. So the state comes into areas where charities and churches once operated, in redistributive welfare. (In fact neoliberalism has done so much damage to economies, throwing many people into unemployment and offering only poorly-paid jobs, that it has been necessary to compensate people with large outlays on social security.)

Beyond this minimum intervention, most mainstream economists justify a wider role of government in intervening in markets where the private sector could possibly provide, but at higher cost or with poorer outcomes than the government, an idea neatly captured by Abraham Lincoln (a Republican we should remember), who said (emphasis added):

The legitimate object of government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done, but cannot do at all, or cannot do so well for themselves, in their separate and individual capacities.

The market can provide health care through private health insurance, main roads through tolls, schools for those who have the means, and so on, but these are generally high-cost ways of doing what the government can do better through public ownership and provision, or through regulation. That is why governments provide public hospitals, public schools, urban roads and so on. Most such services have distributive benefits, but the main reason for government involvement is to compensate for market failure.

Mariana Mazzucato acknowledges that this is the prevailing model among economists, even though the neoliberal philosophy, pursued most aggressively by the Thatcher and Reagan governments in the 1980s, and pursued by many governments since, sees “small government” as an end in its own right, and has been pushing us towards the minimalist model. The idea that the government could do anything better than the market is anathema to neoliberals. (The tension between the economic model and neoliberalism is covered in Miriam Lyons and my 2015 work Governomics: can we afford small government? – a book about the economic role of government without all those funny graphs and equations.)

They shot for the moon

Mazzucato takes the idea of the state one big step further than simply correcting and compensating for market failure, and leaving the rest to the market. It can, and should, be involved in its own right.

Hence her “moonshot” metaphor, a reference to John Kennedy’s 1962 commitment We choose to go to the moon, a project that would never had made first base had it been subject to a cost-benefit analysis before going ahead.

In 2024, in a society that has been infected by the life-diminishing virus of neoliberalism and an ideological shaming of the public sector, her ideas may sound radical. But at times past we have had our own moonshots, most notably the Snowy Mountains Scheme, initiated by a nation-building government. Australian governments have owned many businesses, not only in utilities such as water supply and banking, but also in industries using cutting-edge technologies of their time, including telecommunications, airlines, aircraft and pharmaceuticals.

It was a deliberate policy decision by successive Coalition governments to snuff out the entrepreneurial spirit from public enterprises, articulated in their explicit values, where they state that “businesses and individuals – not government – are the true creators of wealth and employment”.

Mazzucato’s Big Ideas program runs for 54 minutes. In roughly the first half she describes the economic ideas she presents in her 2022 book Mission economy: a moonshot guide to changing capitalism, before going on to specific measures governments can use to become active partners in value-adding enterprises, and not just correctors of market failure.

Ross Gittins on ethics

Ross Gittins has a post on his website with the provocative title Productivity isn’t working, so why not try being more ethical?

Heretical for a well-respected economist?

Not really. He’s asking us to think about the purpose of economic activity, which is to improve human wellbeing. We may all be striving to get an improvement in our personal or national productivity indicators, but he asks “Don’t you think life would be better if we could do all our earning and spending in an economy that generated less angst?”

He refers to work done for the Ethics Centre, about the benefits of a personal and collective life guided and shaped by strong ethical codes. It’s a reminder that the efficient operation of markets depends on trust. Without trust transaction costs are high, and some trades, that could be beneficial to all parties, don’t occur at all.

That’s hardly radical or unorthodox, and certainly not heretical. It’s in line with the work of economic philosophers Thomas Schelling and Russell Hardin. But it’s too easy for policymakers to forget or disregard this important aspect of economics, and to keep designing performance systems – trackers on staff, numerical output metrics, surveillance, requirements that staff be present in the workplace, insistence on sick leave certificates, Robodebt – that are based on an assumption that all people, given a chance, will behave unethically. As those philosophers demonstrate, once such an assumption prevails, then it makes sense for everyone to try to cheat the system.

Life without social media

The technical path of information and communications technology has been fairly predictable. Young engineers and scientists in the 1960s were able to foresee, fairly accurately, developments such as cellphones, GPS systems, high-resolution screens, and fast and low-cost computing. Moore’s Law on the doubling of the number of transistors on a microchip every two years was developed in 1965.

Yesterday’s social media

Those same scientists and engineers would have been incredulous, however, if anyone had predicted how those technologies would give rise to social media (“what’s that?”), and some of its less desirable uses, including cyberbullying, scamming, displacement of previously trusted news sources, dissemination of pornography and violent film clips, and the broadcasting of disinformation – issues brought to the fore in recent times.

Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin ponders what will happen when Facebook stops paying for news. Most likely we’ll get less news from the usual sources through social media, and there will be a further loss of revenue flowing to traditional sources.

To take us further, Claudia Forsberg, an ABC trainee who graduated from university in 2021, posted an article What would happen if Australia were to ban social media altogether?. She acknowledges that around two-thirds of people on the planet have access to social media and use it every day. And she quotes communications experts who say social media has become so entwined in people’s lives that it would be hard to remove it.

But social developments are much harder to predict than technological developments, as those young engineers and scientists from the 1960s were to find out. People may find they have had enough of social media and decide to use other, more established forms of socializing and keeping themselves informed, making use of the marvellous technologies now available, while shutting out advertisers and political manipulators who seek to shape the way we think and behave.