Politics

Rallies for women’s safety – is the noise drowning out the signal?

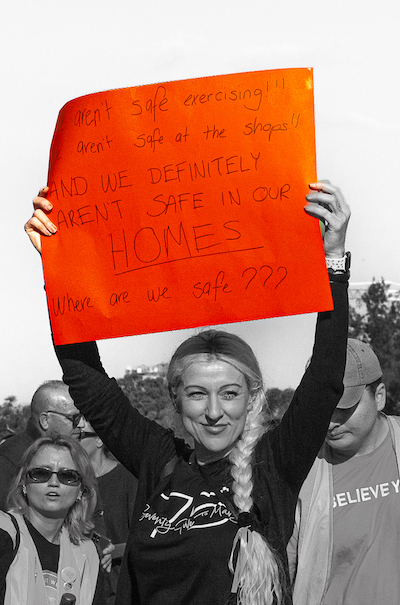

The media has been saturated by news and commentary about the rallies protesting against violence inflicted on women. They have certainly brought the issue of intimate partner violence to the fore.

The rallies

The Canberra rally was probably typical of others in the land. Most people, probably about two thirds women, one third men, were there to show support for women suffering violence and to call for stronger action by governments. There were also women who themselves had been victims of violence, who had much more stake in the process. The mood in the Canberra demonstration is captured by the ABC’s Krishini Dhanji in an 8-minute account on ABC Breakfast.

There were the generic ingredients of a demonstration – haranguing sermons telling people what they already knew (assuming they hear anything from overdriven amplifiers and microphones held too close), and the chants repeated in strident voices. The main chant composed for this rally was “say it once, say it again, no excuse for violent men”, and there were the usual “what do we want?”, “when do we want it?”. (Surely we can do better in choreographing demonstrations.)

Krishini Dhanji explained that the main demand of the rallies’ organizers was for the government to declare a national emergency, and for four other specific measures to relieve some of the burden on women trying to report and escape from an abusive relationship. But those specific priorities would have been unknown by the thousands of men and women who turned up to show solidarity and their recognition of the importance of the issue.

But they became a source of conflict, when the organizers seemed to be demanding that the prime minister agree to a positive response to each of the five measures. Public policy doesn’t work like that, and we’re fortunate that it doesn’t. It’s easy to draw up a list of what look like good ideas, but they need to be evaluated before governments make any commitment. Do they have unintended consequences, are there better ways to achieve the same ends, do they address the actual problem?

The ABC’s Brett Worthington explains how a rather inelegant scene developed in a conflict between the organizers and the prime minister. It appears that the organizers were angry with Albanese for not agreeing with the five measures. In a more general sense, when there is pent-up anger in a group of people, that anger is bound to find an outlet in the nearest authority figure available, and that was the prime minister, who had made the extraordinary commitment not only to attend the rally, but to participate from beginning to end, mingling with and talking to participants. (It was probably the most anxious two hours the police and security staff had experienced since his visit to Kyiv.)

The media has presented the incident as a presentational disaster for the prime minister, but in reality almost everyone at the gathering quietly and politely listened to what he was saying: it was quite a gentle relief after the strident shouting during the march, and the far too long speech that preceded his words. The impression made on the crowd was that the prime minister was simply the target of some ungracious heckling by some ill-mannered individuals, rather than a dispute over policy issues.

It’s a serious problem, but don’t call it an “emergency”

That comes back to the main demand for the government to declare an “emergency”. The word emergency implies that a serious situation has suddenly arisen, and is amenable to quick, corrective action. It’s a construction that raises false and unachievable expectations, and in any case , while this year so far 28 women have been killed by someone known to them – 12 more than in the first four months of 2023 – the trend is downward.

An account of the trend in violence experienced by women, drawing on the ABS personal safety survey, is in a Conversation contribution by Anastasia Powell of RMIT University and Asher Flynn of Monash We’re all feeling the collective grief and trauma of violence against women – but this is the progress we have made so far.

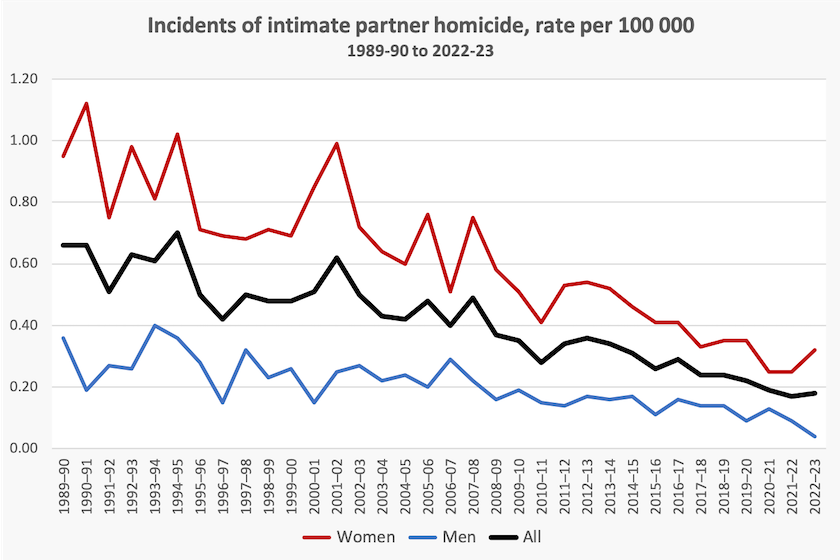

Just a couple of days after the rallies the Australian Institute of Criminology produced the 2022-23 data on Homicide in Australia, complied by Hannah Miles and Samantha Bricknell, which confirms that the incidence of intimate partner homicide has halved over the last thirty years, as shown below.

That is not to understate the seriousness of the issue, but it does suggest that maybe we are doing something right, and it does not support the idea of an emergency.

There may somethng outside the trend in the last couple of years’ figures. There was the downturn during the pandemic – which some people speculate may have been because angry ex-partners were immobilized by the movement restrictions – but whatever its cause it has resulted in the subsequent rise looking rather serious – 28 percent in one year.

It is possible that the sharp fall in real wages over 2023 and suddenly-imposed mortgage stress could be contributing factors to this recent rise. Earlier this week researchers from Monash and Melbourne Universities published in The Conversation spatial analysis of the incidence of domestic violence in Melbourne and Sydney, revealing a strong correlation between domestic violence and unemployment: Our research shows a strong link between unemployment and domestic violence: what does this mean for income support?.

But it’s not a problem that can be fixed quickly. in a 13-minute interview – Should gender violence be declared a “national emergency”? –the Minister for Women Katy Gallagher explains coolly that even the most energetic process to end violence against women will take a generation before it could be eliminated. In part that’s because it can be intergenerational: many perpetrators of domestic violence grew up in violent households.

Governments can do something in the short run, Gallagher explains, to provide more safety for women seeking to escape an abusive relationship. Such measures have to do with matters such as resourcing refuges, training police and other responders, sharing information between authorities, enforcing apprehended violence orders, and reforming bail provisions. They also relate to the resources immediately available to women who suddenly walk out of an abusive relationship, and to this end the government initiatives announced on Wednesday, which include up to $5 000 in immediate support to victims, will undoubtedly help. (The ABC Georgia Roberts provides details about how the measures will work.)

Changing behaviour – all or some men?

Those initiatives are about the imminent danger faced by women in a relationship with a violent partner. The other, longer-term problem, to which Gallagher refers when she talks about a generational problem, is the way so many men are violent towards women – usually their partners. In Patricia Karvelas’ own post on the ABC site – The Albanese government is in the box seat as Australians rally against gendered violence – she writes:

Gendered violence is entrenched, so embodied in our culture it will take an effort bigger than motherhood statements about zero tolerance and lofty goals to end it. It will need dramatically more resourcing and top prioritisation, not just another agenda item on a long list of national issues.

It is possible that some factions of the “Me Too” movement believe that all men are predisposed to violence and that therefore it is futile to try to change their behaviour. That view ignores the reality that there has been progress over the long run: in a historical context it’s only a few hundred years since the condition of women in western European societies was on a par with their condition in Afghanistan today. That condition included the assumption of women’s coverture – “the state of being under the protection of one’s husband”. How many of us realize that it wasn’t until 1974 that married women in the US won the right to open a bank account in their own name. Until recently coercive control was normalized.

Some people look on all men (and all women) as a homogenous community. All men are guilty, even if they don’t realize it – a gender equivalent of the rubbish known as “critical race theory”. By that extreme theory the only reason men associate with women is for sexual gratification and the exercise of power. Those who hold such a view rule out any possibility of men and women living together in cooperation and friendship. A slightly milder version of this view is that action to address gender-based violence must be directed at all men collectively.

Supported by a solid research base Criminology Professor Michael Salter of the University of New South Wales and Jess Hill dispute this model and its collective approach in a paper Rethinking primary preventionmounted on Substack. It’s a long work, but Salter summarises their research in a 9-minute interview on the ABC: Conversations about respect aren't stopping domestic violence, is it time we rethink our approach?. Violence against women is most common in societies where there is gender separation and men and women are unequal. Achieving gender equality is a necessary condition for eliminating violence against women, but it is not a sufficient condition. Public policy, using measures appropriate to particular situations, should address those boys and men who are at risk of engaging in violence against women. Those particular situations may be communities among communities with a tradition of strong male control in families.

There are also men who find it difficult to regulate their behaviour and resort to violence regardless of the victim’s gender.

The main task lies in chhanging the attitudes and behaviour of men who believe there is some special quality that sets man apart from women. They neen to learn what most men already know: it is more fulfilling for men to live a life in which men and women respect one another and are equal than one in which men seek dominance.

We still have a long way to go before we live in a society where men and women live together in true equality and mutual respect. It is notable that in the Human Development Report, Australia lies at position #17 on gender equality – well ahead of the USA and the UK, but still far behind the Nordic countries.

Breaking down remaining barriers of gender separation should help establish better attitudes and behaviour among men. And women who are comfortable relating to men, mixing with men in work and social situations – not just when they’re on their best mating behaviour – should be in a position to assess men’s behaviour before committing to an intimate relationship. Waleed Aly, writing in the Sydney Morning Herald, notes that there are certain identifiable behaviours exhibited by men who may go on to abuse their partners. These include “alcohol, gambling, porn and abusive and neglectful childhood environments”. He stresses that they are risk factors, not firm determinants of behaviour: Holding all men responsible for a violebt minority has failed to keep women safe (paywalled).

While there has been progress in breaking down gender barriers, there are also new forces of resistance, most notably online communities promoting toxic masculinity, for example the Proud Boys and misogynistic “influencers” such as Andrew Tate with millions of followers. Violent pornography, presenting sex in terms of male conquest, is easily available on the internet.

There are longer-established organizations promoting male bonding, such as sodalities in the Catholic Church, “brotherhoods” in Islamic communities, and football clubs in which the game itself has only a minor role in an intense process of male bonding.

There are also powerful institutions and strongly-defended traditions that may not strictly be described as misogynistic in their foundations, but which valorise “male” qualities of aggression and dominance over women, with such values reinforced in single-sex institutions including clubs and boarding schools. Even if they do not belong to such formal institutions many boys and young men lead gender-segregated lives (mirrored by girls and young women who do likewise), coming together socially only in the hope of a sexual encounter, but otherwise preferring the comfort of social and sporting gatherings of their own sex. Is it any wonder that men who reach adulthood with such gender-separated socialization often behave badly when they try to form an enduring partnership with a woman, with all the stresses of marriage and responsibility for bringing up children?

We will know we have made progress when the last girls’ and boys’ schools have gone co-ed, when football and boxing have been consigned to the same history as gladiator fights and duels, when women’s magazines and their male equivalents are found only in the stacks of libraries, and when gender separation has become as reviled as racial segregation.

Let’s not forget mental illness

Although the main issue driving last weekend’s rallies was violence against women inflicted by their partners, public awareness was also elevated by the terrible attack at Bondi, where the perpetrator was deliberately choosing women to attack.

We learn that in this case untreated schizophrenia played a strong part. With reference to this incident, writing in the University of Melbourne’s Pursuit, Kay Wilson explains what the Bondi Junction tragedy tells us about compulsory treatment. Psychiatriists have the power to detain people with mental illness if they assess them to be at risk of harming themselves or others. But research shows that the accuracy of psychiatric assessments is actually quite low.

What this means is that some people may be assessed as a “high risk” when they’re not (and will never be) violent. It also means that other people, assessed as having a low or medium risk of being violent, might slip through the net and later do something violent.

The Bondi attack should bring to our attention the lack of resources we commit to mental health. For those suffering the most severe forms of mental illness those resources have to be publicly-funded, because people with such conditions are unlikely to be able to fund treatment from their own resources.

Matt Berriman, Chair of Mental Health Australia, has resigned his position in frustration because of the government’s failure to develop a multi-agency “all of government” well-funded package to deal with mental health. The government has made some additional appropriations, but it’s only piece-meal and tokenistic.

The ABC’s Evelyn Manfield has a post on his resignation, in which she notes that the opposition has used Berriman’s resignation as an opportunity to criticize the government for neglecting mental illness. That’s hypocritical – in its 9 years in office the Coalition did even less than this government, and in opposition it has not relented from its “small government” line, and has raised scare campaigns at any moves to raise public revenue that could improve health services. Berriman’s resignation is the cry of frustration of someone who expected something better from a social-democratic government, not an endorsement of the Coalition’s policies.

Writing in the Medical Journal of Australia – The mental health crisis needs more than increased investment in the mental health system -- Shuichi Suetani, Neeraj Gill and Luis Salvador‐Carulla, write about the social determinants of mental health. (The social determinants of poor physical health are well-researched.) Besides reforms to use existing resources more effectively:

We also need to address the socio‐economic and structural determinants of mental health and focus on the antecedents and consequences of mental health difficulties. There are many strategies for primary prevention of mental disorders, such as actions to address inequalities, poverty and food security; parental interventions; preschool social and emotional learning interventions; school‐based interventions; child adversity prevention; social isolation prevention; employment‐related stress and mental disorder prevention; and health risk behaviour cessation and reduction.

Political polls

The prevailing story about polls is that Labor is struggling, and could find it hard to be re-elected. That is in contrast with the political wisdom that Australian voters generally give governments two terms.

In the Saturday Paper Jason Koutsoukis gives his impression of the electoral landscape in his article “A race towards minority”: Labor’s fight for re-election.

In his view Albanese is comfortable with what the polls and results of by-elections are showing at this stage of the political cycle. But Labor’s majority in the House of Representatives is razor thin (78 seats in the 151 seat chamber, where 76 seats constitutes a majority), and Labor governments tend to lose some support when they are up for re-election. That’s why a Labor minority government is a distinct possibility – no bad thing in Koutsoukis’ opinion.

Going against Labor is the “cost-of-living crisis”, a framing of our economic problems that gives the impression that people are struggling because of something the government has done in the two years since it was elected. There is also a degree of frustration with the government for its apparent tardiness in getting on with reforms. Sins of omission rather than sins of commission.

But so far the opposition has not put forward anything that would see real wages restored (a more accurate frame than “cost-of-living), or would lead to an improvement in the supply of housing, and it is hard to see what policies they could offer to deal with these problems. Labor is also counting on a boost when the tax cuts start flowing after July 1, and when as-yet unannounced budget measures to ease pressure on households come into effect. Labor is also hoping the Reserve Bank will take into account the government’s fiscal stringency, allowing for at least a slightly looser monetary policy manifest in one or more interest rate cuts.

Those measures should result in immediate improvement in households’ material well-being. In terms of bigger issues, the government hopes that its Future Made in Australia is well-received, particularly in Queensland where Labor did very poorly in the 2022 election.

And of course Labor is likely to focus on the less attractive side of Peter Dutton. He has had little presence in by-elections, but he has to be trotted out in a full election.

The Saturday Paper article is paywalled, but Koutsoukis presents his main findings in a Schwartz Media 7am podcast.

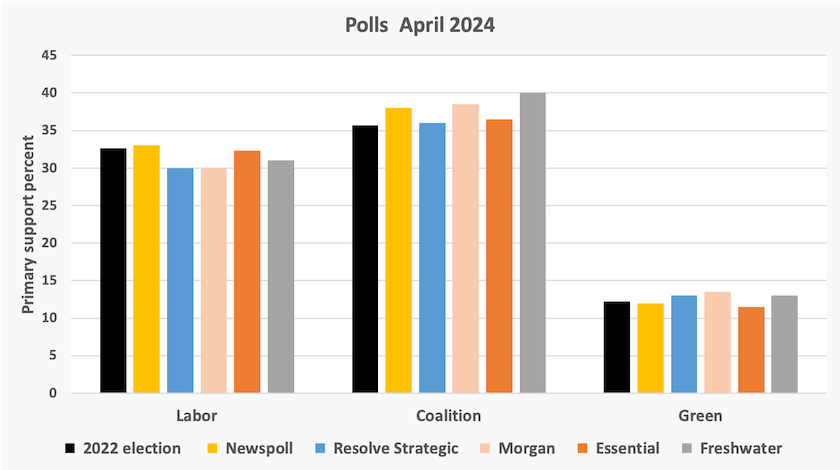

The most recent (April) polls of primary votes for the three main parties, all in April, are shown in the graph below, compiled from data in William Bowe’s Poll Bludger. In round numbers the average of these polls shows Labor’s vote is down about one percent since the election, the Coalition’s is up two percent, and the Greens’ is up a little but less than one percent.

A review of online safety legislation

We covered the ongoing battle between Elon Musk’s X platform and our e-Safety Commissioner last week.

Since then, the government has announced that it’s bringing forward a review of the Online Safety Act 2021, the Act that determines the role and powers of the e-Safety Commissioner.

The government has invited comments, with a 21 June deadline.

Its terms of reference, detailed in the Issues paper, cover:

- cyber-bullying material targeted at an Australian child;

- non-consensual sharing of intimate images;

- cyber-abuse material targeted at an Australian adult;

- the Online Content Scheme, including the restricted access system and the legislative framework governing industry codes and standards;

- material that depicts abhorrent violent conduct.