Other economics

We’re paying more tax. That’s good news.

Australia's average tax rate increase tops OECD countries due to bracket creep and end of tax offset is the headline in a post by the ABC’s Kate Ainsworth.

She bases her statement on recently-released OECD data. She doesn’t link the specific source (poor journalism), but it appears to be the OECD 2024 statement Taxing wages – Australia.

She is right. There has been bracket creep. A period of inflation has seen a rise in nominal incomes (even while, for many, real incomes have fallen), which means income taxes have risen because the thresholds for the brackets are fixed in nominal terms. A rise in taxes resulting from bracket creep has occurred in many OECD countries.

She addresses the often-made claim that our income taxes are too high, a claim justified by the fact that 24.9 percent of taxes collected in Australia are personal income taxes. That is the fourth highest percentage out of the 38 OECD countries.

As she points out, it’s difficult to compare specific aspects of our taxes with those in other countries, because many other OECD countries have a specific social security tax which is on top of personal income tax, and is collected in the same way as income tax, but which is classified separately. If we add in our compulsory superannuation contributions we would probably be around the middle of the pack, but our super contributions by definition aren’t “taxes”. Like “taxes” they’re compulsory, but because they are for personal benefit, rather than for collective benefits, they don’t count as taxes.

Also, because our total taxes are low in comparison with other prosperous countries, it’s a simple mathematical fact the proportion collected by personal income tax is high. If we look at personal income taxes as a proportion of GDP, we’re about mid-range.

That is not to dismiss the claim made by people such as Ross Garnaut and Ken Henry that we are over-reliant on taxes collected from Australian workers. So-called “self-funded” retirees, people with small businesses who use family trusts, and people who have borrowed to speculate in real estate, pay very little income tax compared with workers on normal PAYG arrangements. It’s not that our income taxes are too high: rather it’s that they are collected disproportionately from those who are contributing to our economy, while collecting too little from those living off unearned income.

Max Grundoff of the Australia Institute sets the record straight in his analysis “Australia’s reliance on income tax: a comparison with other OECD countries”, linked from his press release Busting the myth that Australia collects too much income tax. To quote from his summary:

Compared to other developed (OECD) countries, Australia is a low tax country that is not overly reliant on personal income tax when social security contributions are included. Australia is the 9th lowest tax country out of 38 OECD nations and 7th lowest for its reliance on income tax.

Grundoff actually understates Australia position as a low-tax country because in using the 38 OECD countries as a base for comparison, he includes many low-income countries, such as Columbia, Turkey and Mexico. The OECD is no longer a rich countries’ club.

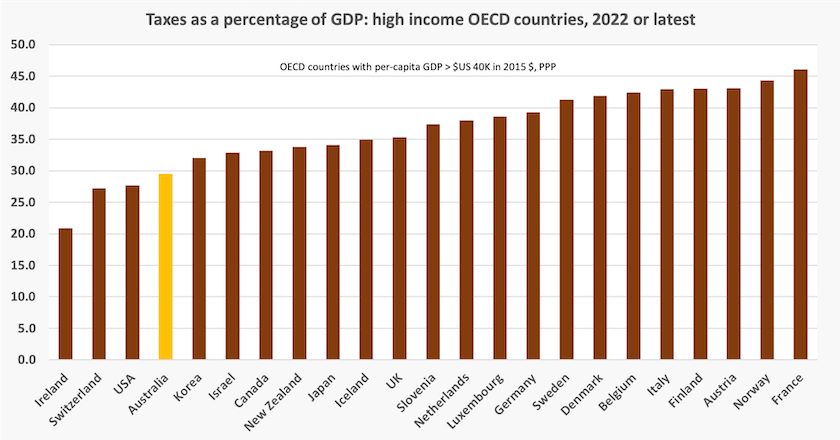

The graph below, which, with updates, has previously appeared in these roundups, compares our total taxes (including state government taxes) with other high-income (>$US40 000 per-capita GDP) OECD countries.

The only countries below us are the USA, a country that continuously runs a high budget deficit which would be unsustainable in any other country, and the tax havens Switzerland and Ireland.

If we are to fund government services adequately, to improve the social wage, to invest in housing and infrastructure, all without adding to inflationary pressure, it is crucial that we lift our contribution to the common wealth through higher taxation. There is a collective avoidance of that reality. It’s a pity we have to do it through stealth, through bracket creep.

What went wrong at Boeing

A series of fatal accidents and incidents has done tremendous reputational damage to Boeing. Air travel is extraordinarily safe, but passengers exhibit an equally extraordinarily bias in overestimating the risk of air travel. Even the more rational traveller, when making a choice between similar options, will go for the airline operating a plane with 0.2 deaths per 10 billion passenger km rather than the one with 0.3 deaths per 10 billion passenger km.

That’s why Boeing has been so badly damaged. But how did it get to that point, particularly in light of its well-established reputation for producing safe, reliable aircraft?

The answer, according to The Atlantic’s writer Jerry Useem, is that it “lost interest in making its own planes” as he explains in his article Boeing and the dark age of American manufacturing.

They once made airplanes

This story is not just about an American airplane maker, or even about manufacturing firms.

It’s about a dysfunctional business culture when a corporation’s objective switches from doing something useful while making a reasonable profit, to making profit as a sole end. It’s about what happens when engineers, who know something about how airplanes are made, are displaced by accountants, who know a lot about how money is made but have little understanding of the physical and social systems of the enterprise. And it’s a story about a business that contracts out its operations to subcontractors who have no interest in the fortunes of the contracting firm, and are merely concerned with filling orders at least cost while meeting specifications in the cheapest way possible.

Shift the context a little and it’s a story about the generic manager in the public service, who knows how to attend to the minister’s political interests, and who can write reports with positive performance indicators, but who knows little about the technicalities of the agency’s operations or how they affect the public. And it’s about the fads of privatization and contracting out – “steering not rowing” to use the idiotic jargon of New Public Management.

Boeing suffers reputational damage. Similarly do our governments – not the particular parties in office – but the entire apparatus of government, as revealed in successive surveys of citizens’ trust in government. If Boeing goes out of business, Airbus and other aircraft firms will grow to fill the gap, but if people lose all trust in democratic government there is not another look-alike entity to take its place.

Higher education debt – we need to reconsider university funding

Many people burdened by higher education debt hope that the forthcoming budget will bring some relief to HECS debt. Those who designed HECS did not envisage it to be burdensome. The balance on HECS debt is indexed to CPI inflation, making it, in theory, an interest-free loan in real terms.

As the ABC’s Lexy Hamilton-Smith explains Once considered a good “social policy”, students say HECS loans are a burden on an entire generation. Her article points out the hardship of HECS debts, particularly in the present situation when incomes are falling behind CPI inflation.

The immediate case for HECS relief is strong, and in view of the government’s political desire to hold on to the youth vote, which is drifting to the Greens, it is likely that there will be some relief in the May budget.

It would be unfortunate if that’s simply a once-off response. HECS was conceived in the 1990s, a period when graduates still commanded significant income advantages over non-graduates.

Those days are gone forever. The reforms of the 1970s, aimed at lifting our tertiary education attainment, initiated mainly by the Whitlam government, have succeeded. At the time the Hawke-Keating government introduced HECS, in 1989, only around 10 percent of the population held a university degree. By now just on a third of Australians hold a degree, and that proportion will grow for some time as the cohorts of young graduates replace the cohorts of non-graduates. By the simple mechanism of supply and demand, the incomes of graduates have fallen in relation to that of non-graduates. Not many people would advocate a return to the days when a university education was enjoyed only by a fortunate few who would enjoy a lifetime high income, but we have a funding model based on the economics of that era.

On the library steps

The Australian Universities Accord, published in February this year, called for a better funding model, based largely on the cost of delivering courses. That would correct some of the absurdities of the Coalition’s “job ready” policy, but would it go far enough in serving societies’ needs from higher education? It advocates fine principles on equity and it recognizes that students in some expensive courses such as nursing will not necessarily enjoy high lifelong earnings.

But missing from its principles is the idea that there may be a case for disproportionately high support, or even free tuition, of undergraduate degrees in general arts and sciences, as a separate category from degrees leading to professional qualifications. Almost all university education has some level of positive externalities – benefits not personally captured by graduates but enjoyed in the wider community. This is particularly so for general liberal degrees. A BA or BSc confers little benefit in job search, but these are the courses which, if well delivered, help people learn how to think and reason, how to learn the lessons of history, how to make wise political choices in a democracy, and to understand when they need to develop new specialist or professional skills in a changing world.

Scams and banks’ incentives

Remember the old scams – the e-mails littered with grammatical mistakes, and names of imagined entities: “The Taxation Penalties Athority”, “Your Toil Road Account”? The scams of today are more polished and convincing at first sight.

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, urges the government to legislate to require banks to take more responsibility for shutting down scams: Australians lose $5,200 a minute to scammers. There’s a simple thing the government could do to reduce this. Why won’t they?.

He points out that in the UK the banks pay out 49 to 73 percent of losses as compensation to customers caught out in scams, while in Australia, if you get scammed, the banks’ compensation to customers is only 2 to 5 percent. In the UK, Martin notes “from October 2024, reimbursement will be compulsory. Where authorised fast payments are made ‘because of deception by fraudsters’, the banks will have to reimburse the lot”.

At first sight that seems to be tough on banks. Why should they pay for people’s carelessness? But it gives them a strong incentive to stop scams in the first place. If the rules are tight enough, and if banks are diligent, there won’t be many payouts.

With the exception of scams where people allow a scammer to withdraw from their own account, and where the victim deposits funds into a foreign account, almost all scams involve payment into the scammer’s Australian bank account – an account bank staff have provided to the scammers, and the deposits of which appear on the bank’s balance sheet. There should be more onus on banks to undertake proper identification and checking before allowing people to open an account. As Martin writes:

Telling banks to pay would certainly focus the minds of the banks, in the way they are about to be focused in the UK.