Politics

Australia vs Musk

The mainstream media has given plenty of cover to the conflict between our government and Elon Musk over our e-Safety Commissioner’s demand that X take down content showing the attack on Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel. For once this high media attention is justifiable, because it brings to the fore issues of national sovereignty and the moral responsibilities of huge multinational media corporations. It’s a global issue, being played out in Australia.

As the ABC’s Tom Crowley explains, in an article on the legal aspects of the conflict, while some media companies have taken down the content worldwide, X has used geo-blocking to take it down only for Australia, which means it can be accessible to viewers in most other countries, and to Australians using virtual private networks.

The legal measures available to our government and to the e-Safety Commissioner are covered in a Conversation contribution by Rod Nicholls of the University of Sydney: Elon Musk is mad he’s been ordered to remove Sydney church stabbing videos from X. He’d be more furious if he saw our other laws.

Dan Jerker of Bond University, writing in The Conversation, warns that global content take-down orders can harm the internet if adopted widely. He asks what is the reach of an individual country’s law.

If North Korea insists on removing spoofs about its regime – such as Always look on the bright side of life – should social media companies comply? Or if the Iran government insists that the ABC take down Sarah Ferguson’s interview with Salman Rushdie earlier this week?

Jerker believes there is a tension between free speech and violent imagery. “For example, some news reporting from military conflicts may be deemed too graphic by some, while others view it as a necessary tool to illustrate the level of violence being committed.” But the attack on Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel clearly falls into a category for which the case for suppression is clear-cut, as it is with child pornography for example, there being no conceivable argument for claiming that its depiction serves any public interest.

JS Mill made it clear that our freedoms and rights are bounded to the extent that they do not impinge on the freedoms and rights of others. There is no unbounded right to “free speech”. That point is overlooked by extreme libertarians, and by Senators Pauline Hanson and the UAP’s Ralph Babet, who disagree with the e-Safety Commissioner’s ban. And although they could not be described as libertarian, Dutton and his shadow cabinet are lining up on the side of the social media companies, which have been so helpful to the far right in spreading fear campaigns and driving political polarization.

There are two more general issues to do with the Internet and public safety, dealt with in a pair of speeches by ASIO Director-General Mike Burgess and AFP Commissioner Reece Kershaw at the National Press Club on Wednesday. From their own but complementary perspectives they are concerned about the way criminals in all manner of activities – people trafficking, drug smuggling, espionage, child abuse, sextortion, manipulating elections in democracies, scams, stealing identities, disabling critical infrastructure, terrorist attacks – are able to use the resources of the internet. These criminals are technologically savvy, they point out.

Both Burgess and Kershaw stressed the difficulty faced by intelligence and law-enforcement authorities in dealing with criminals who use end-to-end encryption. ASIO and the police can obtain authority to eavesdrop on Nazi chatrooms, for example, but the codes are uncrackable, unless they can secure cooperation from the enterprises that host the communication channels. That cooperation is not always easily obtained.

Burgess spoke mainly about ASIO’s technical expertise – with all the enthusiasm of one whose first degree was in electronic engineering. Anyone whose view of ASIO is shaped by its Cold War era obsession with communism and the blind eye it turned to right-wing violence, or by dramatic representations of spy agencies, would do well to update their impression by listening to Burgess in this or one of his other public appearances. He presents himself as a committed liberal, and the agency he heads as one dedicated to community safety free of any ideological filter.

Kershaw’s presentation was more passionate, and was partly about what individuals can do to protect themselves and their children from criminals operating on the internet. He spoke as one who has seen the terrible damage criminals can do using social media and other internet-based vehicles:

Some of our children and other vulnerable people are being bewitched online by a cauldron of extremist poison on the open and dark web.

And he had particularly strong words for social media companies:

Social media companies are refusing to snuff out the social combustion on their platforms. Instead of putting out the embers that start on their platforms their indifference and defiance is pouring accelerant on the flames.

Americans’ trust in institutions has fallen to low levels. That should worry Australians.

“As far as stereotypes go, brash national self-confidence has long been a defining feature of how Americans are viewed abroad. In 2006, when Gallup first started asking Americans about their trust in key institutions, the country ranked at the top of the G7 league table, tied with Britain. In 2023, for the first time, America came last.”

That quote is from an Economist article America’s trust in its institutions has collapsed. It sits behind the Economist’s paywall, but the Gallup survey to which it refers is freely available.

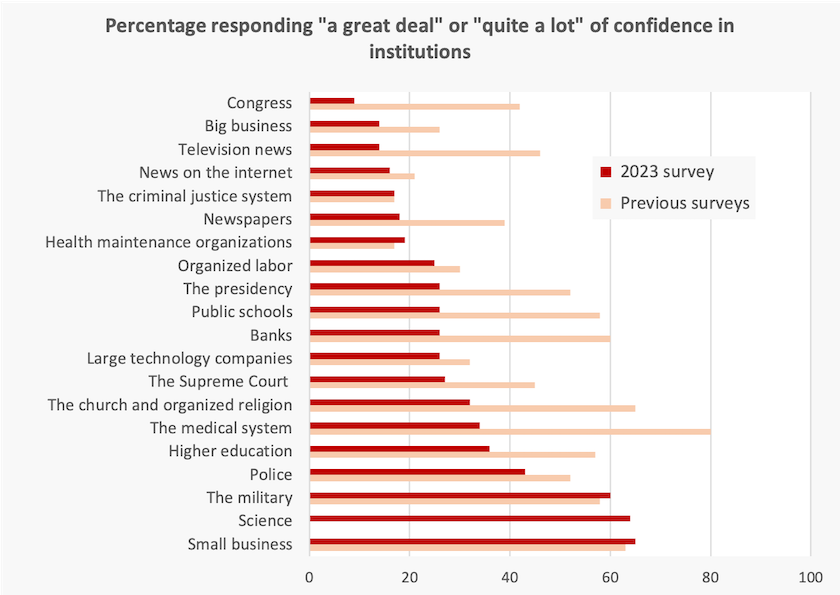

In its survey on confidence in institutions Gallup pollsters asked respondents to indicate their confidence in 20 institutions, using a 5-part Likert scale. The results, in terms of the percentage who show at least some confidence. are shown below in a graph. Alongside each red bar is a bar in a lighter colour showing the results in earlier surveys – mainly in 1973, but some quite recent, such as 2015 for universities.[1] This comparison gives some indication of the extent of the fall in confidence.

The Economist article also mentions a companion Gallup poll – U.S.: leader or loser in the G7? – which compares the US results with similar surveys in other G7 counties. The US stands out among G7 countries as having the lowest confidence in key national institutions – the military, the judicial system, the national government and the honesty of elections. In Australia we can take some comfort in some differences with the US. Our highest court is not politicized, we have preferential voting, we have not been subject to a dopey “defund the police” campaign, and we have the ABC as a check on commercial media, but in many respects Australia is suffering the same mistrust in institutions as the US.

The Economist’s author uses the term “collapse”, implying a sudden fall in confidence, but most of the Gallup data, which is generally collected annually, shows an erosion over a long period, before there is a steeper fall in the last ten years or so. This lends support to the idea that Trump took advantage of a situation ready to be exploited by a populist demagogue, in the same way that Hitler did in 1933.

One may dispute the analogy with Germany: in 1933 the Weimar Republic had fallen apart, the Treaty of Versailles had left the country impoverished and humiliated, and the Great Depression was at its height. At the time of Trump’s ascendency nothing similar was happening in America – except, perhaps, a rising consciousness that China was on a path to displace America as the largest world power.

A focus on objective conditions, however, overlooks the role played by fear and anger in fomenting discontent.

Fear, in itself, is a normal human emotion, essential for survival. Fear of an early death, for example, can motivate people to give up smoking, to drive carefully, or to get vaccinated. But when fear is intensified, our emotions are stimulated, and when our fear gives way to anger, our capacity to think clearly is dulled. Hitler knew this in 1933, just as Putin and Trump know that now. Fear and anger can be generated for political ends, even when there isn’t much about which to be fearful or angry.

We now have the extraordinary power of social media to stimulate, amplify and disseminate fear and anger. That’s the business model of the social media companies. In times past fearmongers had few opportunities to spread their messages, but now the world is open to them, and they have the added benefit of anonymity.

On the ABC’s Future Tense program Antony Funnell interviews four leadership and social psychology experts on fear and anger – the complicated emotions that govern our world. (Funnell summarises the main points of this interview on the ABC website: Fear and anger are dominating our world right now, but are we being manipulated for profit?)

What these experts have to say about social media helps us understand why the standoff between our government and Elon Musk is such a major issue: huge profits are at stake.

They also help us understand how the politics of fear works. Fear of asylum-seekers released from detention, fear of people coming to our country in small boats, fear of indigenous Australians cancelling Anzac Day and taking back their land, fear of the market value of our house falling. With a little reflection and a focus on the facts we realize that these fears are all groundless, but when our emotions are sufficiently stimulated we don’t think clearly.

Experts on the program explain how different people, in different situations, react to heightened fear. Some people may react violently as they did in Germany 90 years ago, and as we have seen in certain incidents – the Cronulla riots in 2005, the Wieambilla murders in 2022, and the Wakeley riot earlier this month.

But more often people’s reaction is to turn off, to disengage. Dutton and his colleagues exploited that reaction in the Voice campaign. They didn’t mount an argument against the constitutional amendment, even though there were quite respectable arguments that could have been stated. Rather, the message was “if you don’t know, vote no”. Turn off.

That’s the simple and easy weapon of the right. They use a fear campaign designed to thwart reform, rather than engaging in an argument about the merits or otherwise of policy proposals. A situation of elevated but not clearly articulated fear, amplified by the media’s sloppy use of words like “crisis”, is the perfect environment for the fearmonger in a democracy.

The media, including the ABC, do not serve us well when they allow the opponents of reform to avoid engaging in policy debates. Had they forced Dutton, Mundine and Price to articulate arguments against the Voice, the referendum may still have been lost, but without the bitterness and lingering belief that lies and disinformation will always triumph in any attempt to achieve reform in a democracy. Such cynicism about democracy is corrosive. Perhaps Trump deliberately uses such fear campaigns because he wants to destroy democracy – the attempt by Trump Republicans to start a violent conflict on university campuses is chillingly similar to Hitler’s early moves. But to give him the benefit of the doubt, Dutton’s campaign on the Voice was simply based on his failure to understand history and the fragility of democracy.

In a few weeks the government will present a budget, probably including some modest reforms. Will the journalists in non-aligned media take the effort to get the opposition to mount considered criticisms of government policy, and to articulate their alternatives, or will they allow the opposition’s lies and disinformation to go unchallenged?

1. “Science” has no pale red bar because it has not been previously surveyed. ↩